Comic Book Historians

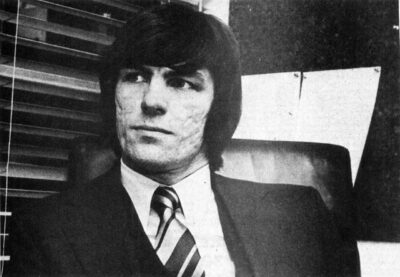

Carl Potts: Editor, Artist & Professor Part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

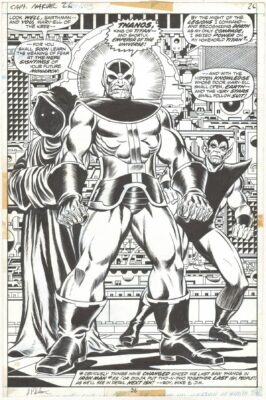

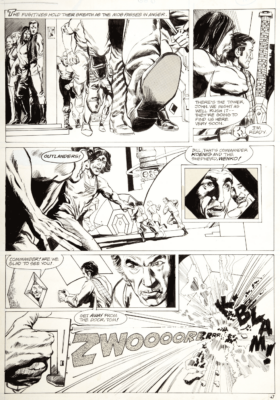

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview former Marvel Executive Editor and Epic Imprint Editor in Chief, Writer, Artist & Professor Carl Potts in part 1 of a 2 parter, where we discuss his early days at San Diego Comic Con 1973, breaking into DC Comics with fellow fanzine artist, Jim Starlin, assisting and learning comic book production with Neal Adams & Dick Giordano at Continuity Studios, his Advertising work, and starting as an Editor at Marvel comics working with artists like John Byrne and Bill Sienkiewicz. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview former Marvel Executive Editor and Epic Imprint Editor in Chief, Writer, Artist & Professor Carl Potts in part 1 of a 2 parter, where we discuss his early days at San Diego Comic Con 1973, breaking into DC Comics with fellow fanzine artist, Jim Starlin, assisting and learning comic book production with Neal Adams & Dick Giordano at Continuity Studios, his Advertising work, and starting as an Editor at Marvel comics working with artists like John Byrne and Bill Sienkiewicz. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians

Alex: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians Podcast. I’m Alex Grand with my cohost Jim Thompson. Today we have a very special guest, Mr. Carl Potts. Carl has many titles to his name as well as professor, writer, editor, inker, layout artist, penciler. He worked in the early seventies with Neal Adams in Continuity, and then also went on to Marvel and other projects. Carl, thank you so much for joining us today.

Carl: My pleasure.

Jim: All right, so Carl, I always like to start at the very beginning, and I know you were born in the early fifties in Oakland, California. I had read that you were raised in the San Francisco Bay area but also in Hawaii. Can you kind of break down when you were at different places?

Carl: Yeah, I was a Navy brat. I was born in Oak Knoll Naval hospital in the Oakland Hills, and lived in various places around the East Bay Area until I was four, I believe it was. And my dad was stationed on Oahu and Honolulu, and so we live for two and a half years in Navy housing and Honolulu. So I went to kindergarten and first grade at Nimitz Elementary School in Honolulu, which on a recent trip to Hawaii I visited. It is still open, still there, still operating. It’s the only school I went to from elementary through high school that is still open and operating. It’s very strange. But the first one I went to is the only one still standing.

Carl: After that we moved back to the Bay Area and pretty much stayed there for most of my life until I moved to New York. We did have one short six-month stint in San Diego when I was in second grade. My dad was posted down there for a short time. Then we came back to the Bay area.

Jim: And what did he do, he was in the Navy?

Carl: Yeah, he was a 20-year man. He was Chief of Damage Control, which means that if there was any ship damage including battle damage during, he was in World War II, he had to deal with that. But often that also meant that they were the master carpenters. So he was an amazing carpenter. But he was on a sea plane tender, a PBY seaplane tender, so they would often have to rendezvous with sea planes that were out of fuel or damaged in the middle of the ocean, and go out there and try and get them up in the air again.

Jim: Yeah. My dad was on the Santa Fe and I think the Wasp during the war as well. So I know all those stories. Tell a little bit about your upbringing. You said your dad’s in the Navy, but what else can you tell us?

Carl: Well, my father and my mother met shortly after World War II in the Bay Area. My mother and her whole family had been prisoners of the Japanese in the Philippines during the war for over three years. And even though my maternal grandmother, her mother was Japanese, born and raised, she had married an American, and considered herself an American from that point on. So they were in the Philippines when the Japanese took over and they took all of the allied civilians and put them in prison camps. The biggest one was Santa Tomas University campus, this big square city block with big walls around it that was in the heart of Manila.

Carl: And at first they hated my grandmother for marrying the enemy. They weren’t going to put her, this Japanese woman civilian in a prison camp. But she was a tough lady. I didn’t realize when I was growing up, she was just grandma to me. But she worked her way up the chain of command to the general in charge of Manila and convinced him she was American by choice, and he finally relented and wrote her a pass to get into the prison camp to be with her husband and her children. As far as I know, she’s the only Japanese civilian voluntarily imprisoned by the Japanese during the war, at least in the Philippines.

Carl: But they were in there for over three years being progressively starved, and occasionally the camp by thai, the secret police would come in and help people out and they’d never be seen again. It was really brutal stuff. And when MacArthur came back, he sent a force called the Flying Column, a hundred miles behind Japanese lines to get into Manila and free those prisoners. And if they hadn’t been successful, I wouldn’t exist because my mother was in that camp.

Carl: So that’s actually part of a giant World War II graphic novel I’m currently working on, that’ll be published by the Naval Institute Press called The Flying Column that I wrote, and I originally started doing layouts for, and Bill Reinhold was going to do all the finished art on. But it turned out that I was just not producing the layouts fast enough. So Bill took over. And he’s doing all the art on them, and he’s doing it in ink wash that we then turn into sepia tone, so it’ll have that 1940s look.

Jim: Oh that’s exciting.

Carl: But after the war, or while the war was still going on, my grandfather, who was from Alabama, took his Japanese wife and all his half-Japanese children to his family in Alabama while the war is still going on. So my poor younger uncle got in fights every day in high school for the rest of the year, for about a month because all the bullies there would jump him. Fortunately, he’d been taking boxing lessons in Manila.

Carl: But my mother and some of her sisters, and eventually most of the rest of the family moved to the Bay area, and that’s where she met my father, and they decided to get married. And back then, even right after the war, there were still these laws that if you were half Japanese or more, you couldn’t marry a Caucasian person in California. So they had to drive up to Washington state where the laws were different, in order to get married.

Carl: And then he got posted around. He was in Guam where my sister was born and then back to the Bay Area where I was born, and we took off from there. But after we moved back from Hawaii, we were basically in San Leandro, California, which is below Oakland and above Hayward. And I pretty much grew up there until I was about 21 or 2, and I decided I was going to move to New York and become a comic book artist, very naively. Even in college, it was close enough that I didn’t even move out of the home. So I’d never lived on my own.

Carl: And in the Bay area at that time were living some professional comic book people who had got tired of New York and decided to move to the beautiful Bay Area, including Jim Starlin and Alan Weiss and Frank Brunner, and particularly Weiss and Starlin were very, very nice to me, and always invited me over when I had new art samples to show. They’d give me critiques.

Carl: And eventually Starlin got assigned to do, basically over a four-day weekend, draw a whole issue of Richard Dragon Kung Fu Fighter for Denny O’Neil who was editing it at DC. They needed it in a rush. And so he pulled me in to help on some backgrounds and background characters, and Alan Weiss helped him pencil the main stuff. And Allen Milgrom make the whole thing to try and make it look somewhat uniform. But lord knows Milgrom had his hands full with my stuff back trying to make that come up to the standards.

Carl: Anyhow, so when I told Starlin I was going to move to New York, he asked me if I knew anybody out there. And I said, “No, I did not.” And he said, “Hmm, I’m going to make a call.” So he ended up calling Al Milgrom and Walt Simonson who shared an apartment in Forest Hills Queens, and said, you know, “if this kid comes out there, would you guys be willing to put him up while he gets his feet under him?” They said, “sure.” They’d never met me. They had no idea who I was. They just took Starlin’s word that I was decent folk.

Carl: And so I flew out there and arrived on a red eye, made it to the apartment building in the late morning. And I didn’t realize those guys kept nocturnal hours. So I actually woke them up at around 11 in the morning. And it turned out that, you know, not only was I kind of star struck, suddenly hanging out with Simonson and Milgrom, but that living in that same building where Bernie Wrightson and Howard Chaykin, and they’re always paling around all day long.

Carl: And I was just like, you know, I didn’t know what the hell to do. I was just flabbergasted. I was suddenly in the mix of with all these people.

Alex: And this was in 1974, right?

Carl: Five. Summer of ’75.

Alex: ’75, okay.

Carl: And if you recall, your history, that is right when Atlas collapsed. So all the people who had gone to Atlas to work were rushing back to Marvel and DC to try and pick up work. So that was like the worst possible time to try and break into the business.

Jim: Now before that though, you had made some other contacts and including meeting Neal Adams when you were still in California, right? In ’73? At your first San Diego Comic Con. Talk about that for a few minutes.

Carl: Yeah. I drove my Pinto hatchback from the Bay Area down to San Diego and then the convention was being held at a motel near the airport. That’s how far long ago this thing was. And the major guests there that year were Neal, Jack Kirby and Carmine Infantino. And I had a portfolio of really, really lame art. And not even any continuity stuff. It was mostly typical mistake for, you know, fans trying to show their work. It was pinup type stuff. And I worked up the nerve to show it to Neal. Neal looked at it and said, “Hmm.” Handed it back to me and said, “It’s not even worth commenting on,” and turned around to walk away. And I don’t know how I worked up the nerve, but I just said, “Well could you at least tell me what to work on?” So he turned around and he proceeded to name every aspect of drawing and composition and storytelling, and you know, layout, everything, and anatomy, everything. And said, “You know, if you worked real hard for 18 months I might be willing to look at it again.”

Carl: So when I got to New York, I took him up on in his offer a little bit later. But first, Starlin would go back to New York once in a while to arrange for his next batch of projects or whatever. So he kindly timed one of his visits with my visit back there. So my second day in New York he took me up to the Marvel offices, which were the ones on Madison Avenue at that point, and introduced me around, and I got to show my work. And sold my first piece to Archie Goodwin of all people, who was editing the black and white magazines at the time.

Alex: For Marvel.

Carl: Yeah. And there was a science fiction magazine that he had that he wanted to get a piece of art for the subscription ad. So he bought my pencils for something and then Simonson at that. So my first professional job selling something, I get Walt Simonson in it. And I got Goodwin buying it. My head was in the clouds. And then I … Go ahead.

Jim: That was your first professional at Marvel. But you had done some Fanzine work before that, including the one that you did with … I think you met these guys in at the same convention that you met Adams, right? The Venture people? Who are very important in your career. I mean, they come up periodically.

Carl: Yeah. At that convention I made connections with other artists. Ironically, I had to go to San Diego to meet a bunch of other artists from the Bay Area who I didn’t even know, who were also into comics and trying to break in. And that included Steve Leialoha and Al Gordon and then Frank Cirocco, Gary Winnick and Brent Anderson who were all from the San Jose area in South Bay.

Carl: And so that’s my initial connection with all those folks. And up until that point, I was in total ignorance that there were a lot of other people in a similar situation and mindset as I was living near me.

Jim: So tell us a little bit about Venture.

Carl: Venture was basically Frank Cirocco and Garry Winnick’s fanzine, and they were also good friends with the Brent Anderson – so he always had work in there as well. And I did just a little bit of work for them. But when they heard I was going to move to New York and try and break into the mainstream comics, they used me to try and help tease Neal Adams to do a cover for them, which was … I think the fact that they got that cover out of Adams with me kind of tickling the subject matter from the inside, there at Continuity, I ended up getting that original art for a while. But then Garry Winnick was so proud of that piece because it had Neal Adams drawing a character he created, that I ended up giving it back to him.

Carl: But let’s see, where I was going?

Jim: And Cirocco and Winnick actually ended up … Did you help get them jobs at Continuity at some point?

Carl: Yeah, a bit. They came out and decided they were going to … The year after I got out there and I got established at Continuity, they decided they were going to try and do the same thing. So I introduced them around. And Neal and Dick Giordano liked them enough to have them work up there for a while. And then a year or two … Brent Anderson came out with them too, but Brent I think was more freelancing as opposed to just, you know, working up at Continuity. But he was there a lot. Then they all went back to California for a little while. And then a year or so later, Brent Anderson came back out, this time accompanied by Joe Chiodo. And Tony Salmons, I believe too came out somewhere along the way.

Jim: Oh because he did some work for Venture too. I know he inked something.

Carl: Yeah, I remember. So Tony, I think was not from the Bay Area though. I think he was from Arizona or somewhere still out west, but not the Bay Area. But anyhow, before I got to Continuity, when Starlin was still showing me around the Marvel offices, he took me into the British reprint department where the editor was busy chopping up the 22 page stories in half for the British weekly market, and they needed new splash pages for the second halves. And so they’d often give the new people a shot there. And I ended up going out of there with a handful of assignments for new splash pages for the British reprints.

Jim: That’s right, because Tom Orzechowski got … That’s where he started over at Marvel too, I think, as I remember. You knew him as well, right? He was one of the people.

Carl: Yeah. In the Bay Area, in addition to Weiss, Starlin and Brunner, Steve Englehart moved out there, and Orzechowski was there. And for a while a lot of them had this house they were renting altogether in the Berkeley Hills, which was really nice. I’m not sure if there was anybody else that moved out there or not from back east.

Jim: Now you’d become interested in comics going back to early days. You were interested in comics. And I had read somewhere that you had really started with DC war titles, that those were ones that were kind of your first love. Was that accurate?

Carl: Well, I’d been reading comics before then. Just about anything I could get my hands on, I’d read. And then, you know, if I was home sick from elementary school, my mom, if she went to the drugstore, would go to the spinner rack and grab a handful of things, usually stuff I wouldn’t normally have bought for myself, like Lucille Ball comics and you know, things like that. But occasionally she’d get something I’d like. But I’d read them all. I just love the form and visual storytelling.

Carl: But when I started mowing the lawn and getting my own money, yeah, I’d go down, and usually it would be DC war title. That’s when the differences in the art started really jumping out at me and looking at people like Joe Kubert and Irv Novick and Russ Heath. You know, the art just looks so amazing to me.

Jim: And then you ended up sharing, you were in the same space as Russ Heath when you went to Continuity, right? He was right behind you?

Carl: Yeah, Russ was sitting at the table behind mine in the main front room at Continuity.

Jim: And did you work with Kubert at all?

Carl: I met him a few times. The only time I really worked with him at all is later on when I was executive editor at Marvel at that point. That was that silly period when they had five of us being simultaneous editors-in-chief. And he was doing new Tor, and new Abraham Stone work for Epic. And so I worked with him a little bit on that. And Irv Novick, I don’t believe I ever met.

Carl: But when I used to go to my father’s PX in Alameda, I’d buy comics there too. And one day I went in there and the first Marvel I ever really saw was Sergeant Fury number one. And it was sitting on the racks there, and it just looks so different than any other war book I’d seen.

Carl: So I picked it up and took it home and I read it, and I did not care for Kirby’s rendering style at all. But every day I kept pulling that thing out of the drawer and rereading it. And it wasn’t until years later I realized that it was a combination of the dynamics and Kirby’s storytelling, and Stan’s bombastic dialogue, that really drew me in. And I saw house ads in there for all the other Marvel titles. So I started picking them up. And before long I was just buying Marvel stuff. I didn’t buy any DC stuff for quite a while – I think until Ditko went over there and started The Creeper.

Jim: Because you would’ve been about 12 or so when Marvel was really kicking in, the Marvel age of comics. And I had read that Ditko is one of your favorites of that period.

Carl: Yeah, his work on Spider-Man and Doctor Strange just blew me away. I was much more of a Ditko person than a Kirby person, although I liked them both and appreciated them both. But Ditko, the fact that he made Spider-Man just come to life with all these, you know, strange body language positions and actions, and creating whole new worlds with Doctor Strange, I was just fascinated with what he was able to do.

Jim: Yeah, he’s my favorite too. Those two Spider-Man annuals just give you everything you need to know in terms of body, but also the dimensions and things with the Doctor Strange crossover. I love that stuff more than Kirby.

Carl: The second annual is one of my all time favorite comics.

Jim: Yep, mine as well.

Carl: I just thought I would get one thing out before I forget. Starlin’s got, as you can tell, major brownie points in my mind, because in addition to after taking me up to Marvel and introducing me to Goodwin and others, and this British reprint department, when I got those assignments, I didn’t find out until a couple of years later, that the only reason I got those British reprint assignments is that the editor took Starlin aside out of my earshot and said, “I’ll give this kid some work if you do a cover for me.” Starlin did that and he never told me. I had to find out from Milgrom a few years later.

Alex: Oh really? That’s cool. So he was looking out for you.

Carl: Yeah, he’s got major gold stars next to his name in my book.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome.

Jim: All right, Alex, take it away.

Alex: So how did you start work at Neil Adams’ Continuity Studios in ’75? Did he remember you from the San Diego Comic Con a couple years earlier? Tell us about that.

Carl: I ended up calling up Continuity soon after I arrived in New York, and reminded whoever picked up the phone, who I assume was Pat Bastiane who was usually doing that at that time. And told him that, you know, Neal had told me two years before that if I worked real hard for 18 months he’d be willing to look at my work again. So I was in town. I was wondering if I could come up and show my work again. And she checked with Neal, she said, “Come on by.”

Carl: And that’s what I did and I was very nervous. And this time I actually had continuity type samples in there – sequential visual storytelling as opposed to pin-ups. I’d learned that lesson really well. And they were just gearing up then to start packaging these large black and white magazine comics for Charlton that were based on TV shows, $6 Million Man, Emergency!, and Space:1999. And they were looking for some young guys to come in and pencil them under Neal and Dick’s tutelage. That way they could afford to package these things and get them to Charlton. So they asked me to be one of those people. And the only empty desk at that time was at the left hand of Neal’s. I ended up working next to Neal for three years.

Carl: But it was very daunting and intimidating. There wasn’t a lot of like hands-on lessons. It was more like I would take whatever I did originally and see how to evolved through all the process and what came out at the end, and see what changes were made and figure out why. And that’s how most of my lessons were learned out there.

Carl: But Neal would have us all do these really tiny thumbnails. You’d take an 8 ½” X 11” piece of paper, fold it into quarters, and then each quarter was a thumbnail for a full page. So it was very small. And then he’d look at them and with his Flair pen, he would either strengthen the drawing, or in some cases he would just ignore what you’d drawn and draw something else without penciling it just with the Flair pan.

Carl: And then he had one room in the back that had two large old Art-o-graphs, which are fancy opaque projectors that project straight down onto a desk and you can adjust them for the size of the magnification and the focus. And we would take those tiny thumbnails, blow them up on the full size art board, and trace off the basic shapes, and then take those and do the finished pencils from them.

Alex: Oh, okay. So those thumbnails kind of acted as a layout in a way.

Carl: Yeah. And then, when Neal approved the pencils, then they went to Dick Giordano. He would often do a lot of the major characters and faces and so on.

Alex: The inking stage?

Carl: Yeah. And occasionally though other people would come in. I have stuff on those pages that Russ Heath inked, that he was available to do some inking work. So they would have him do some of the major characters too. Other people would come by. Vincente Alcazar would come by and visit once in a while. He’d be inking. But Dick’s assistants at the time where Bob Wiacek, and Terry Austin. They were doing a lot of the backgrounds and background figures.

Jim: Was Joseph Rubinstein there too at that point?

Carl: I think that was early in his stages there as like a high school intern or something like that.

Jim: That’s what it was.

Carl: And then a little later on, Denys Cowan was doing the same thing. He was there a lot. And then another guy named Joe D’Esposito. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with his work, but he’s a very good painter. He was there. So anyhow, by the time Neal, Dick, Russ, Terry, Bob got through with my pages, they looked fabulous, based on what they were originally given. So that’s how I learned a lot, by looking at how that whole process worked.

Alex: That’s kind of a cool, almost like a conveyor belt, but a very creative one.

Carl: Yeah. And then at times people would come to visit from out of town for a while, hang out in the studio, and if it looked like they were twiddling their thumbs too much, Neal or Dick would say, Hey, you want to do some of this or that, and you’d have other people inking your stuff and you’d see neat, interesting takes on the final art based on what you’d given them. And it was a great way to see how different artists approach things, and get you out of your default ruts on how you approach drawing or rendering things.

Alex: Right. So tell the audience what exactly is the Crusty Bunkers?

Carl: That is a name for a loose amalgam of creative talent, that basically whoever happened to be at Continuity Studios when Continuity needed to get something inked quickly for a client. So mostly it was Dick Giordano and Neal Adams, but often Russ Heath, who was there too. Occasionally Jack Abel who rented space up there. And then also renting space further back along the row were obviously Terry Austin and Bob Wicheck. But you had Larry Hama and Ralph Reese. And there were other people that would come and go all the time. Alan Weiss ended up moving back to New York, so he was part of the Crusty Bunkers before he moved out of New York and then after he moved back. It just evolved constantly, who was involved.

Carl: There was a guy who did very little in the comics business but was very, very talented named Ed Davis who did a little bit of Crusty Bunkers work as well.

Alex: Hmm. So Continuity kind of functioned as a shop, kind of like the 40s shops, like the Eiger and Eisner shop. And Continuity was basically like that in the 70s. Is that correct?

Carl: I guess in a way, although it was also kind of like a social crossroads. It was like the neutral ground between Marvel and DC, and places people could just come and hang out and shoot the breeze or maybe pick up a little bit of work. It was a very interesting atmosphere. I mean there was a lot of strange personalities up there and people visiting. A great sitcom could have been created out of that place.

Alex: Huh. That would be fun. So tell us about phasing out of Continuity and entering Marvel. Around what year was that?

Carl: Well, actually it took a bit longer than that because I got into doing storyboards mostly for my living. That’s something else that Continuity introduced me to. And I was able to make a lot more money drawing storyboards than doing comics. I would be paid the same amount for drawing a single frame of a storyboard as I would for penciling a full page comics. And the storyboard could be very loose, whereas the comic stuff had to be very tight.

Carl: So I ended up doing that most of the time. I ended up going on staff for a couple of years at an Interpublic company at the time called Marshalk, that I think got absorbed by McCann Erickson at some point. But I always drew comics when I should have been sleeping and on weekends. And including some stuff for DC, I worked for Paul Levitz on Adventure Comics for a while. I did some Aqualad stuff and some Nightwing and Flamebird stuff. And then I created a new character called Cobalt and plotted in two or three episodes for that before the implosion killed that project.

Alex: The DC implosion of ’78, okay.

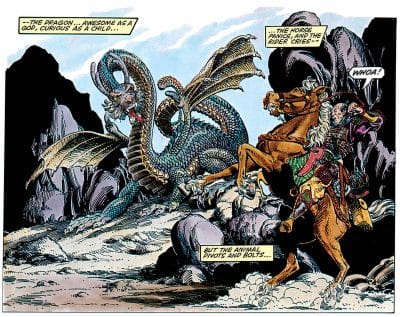

Carl: Yeah. It never got published. And then it was sort of a spin-off of the Goodwin, Simonson Manhunter universe, part of the DC universe. And then I would occasionally do bits and pieces of work for Marvel. And then Archie Goodwin at that point was overseeing Epic Illustrated magazine. I sold him a few short pieces. And I sold him my first real creator-owned creation called Last of the Dragons, which was serialized initially in Epic Illustrated.

Alex: And that was with the Denny O’Neil and that was 1982?

Carl: Yeah, that’s when it started and it ran through ’83, yeah.

Alex: Okay.

Carl: I think it was six installments. That one kind of spoiled me because I just came up with this idea, started drawing it, plotted it out. And I showed my drawings to Terry Austin, at Continuity and Terry goes, “That looks great. I’d be interested in inking that.” At that point, Terry had become like one of the hottest tinkers in the business. And so I take it up to Marvel and I show it to Archie Goodwin, and I say, “Archie, I’m working on this thing. Here it is. Here’s what it’s about. Is this something you’d be interested in Epic Illustrated?” He goes, “Yeah, I like that. It’s great.” And I say, “Well, I’m not really confident with my scripting yet. Is there any chance you’d want to script it?” And he kind of smiled and he shook his head, “No, you just find someone else to script it.” So I walk outside and there’s Denny O’Neil. I say, “Denny, would you be interested in working on this?” And he looked at and he goes, “Yeah, I like this.” So I needed a colorist, I walk into the bullpen, there’s Marie Severin. I go, “Hi Marie, check this out. Is this something you’d be interested in?” She goes, “Yeah.” Then I run into Jim Novak, I need a letterer.

Carl: So I just thought that’s the way things naturally happened. Everything fell that easy. It’s like I got so spoiled that when things didn’t happen like that in the future, it was, it was very frustrating. But one of the best compliments I ever got was from Archie about halfway through the series. I’d deliver each chapter up to him and he was looking through either chapter three or four when I delivered it, and he kind of shook his head and he looked up at me, he says, “You know, I should’ve scripted this.” He was sorry that he hadn’t taken on the job. And I just felt extremely flattered to get that out of someone of Archie’s stature.

Alex: Wow.

Jim: Can you talk about Archie a little bit? Because everybody does, and they all have sort of, I’ve yet to hear a bad story about him, but what was your experience?

Carl: It would be, it’d be very hard to find a bad story about Arch. He was probably the most, when he was around, he was most universally admired and liked professional in the comics business, I think. Everybody knew he was smart as a whip. He was extremely talented. He could write rings around most everybody. And he was a great editor too. He’d have great insights and he was also a very good visual storyteller. He would occasionally do layouts for the stories that the artists would draw based on his work. It was kind of a bit of a cartoony style. I remember those cartoons he used to do on the inside-

Advertisement

Jim: Sure.

Carl: -covers of the, yeah, the Epic Comics. But he was a very good at visual storytelling as well.

Alex: Yeah, and I think when he wrote his scripts, he always had the visual aspect in mind. That’s what he was kind of known for, I think. Right?

Carl: Yeah, I think so. And I don’t know if he did thumbnails for all of them, but he did for some of them. And just, you know, he, you know, he was older than I was and I kind of, you know, the next generation before me and I kind of, you know, looked up to him and revered him, I think most people did. But he was like, you know, so easygoing and to be around, he wasn’t pompous or stuck up at all, he the exact opposite. He was very approachable.

Carl: He was also a hell of a practical joker. He, he would often put his body at risk by doing these amazing pratfalls down stairs and all that on purpose to get a laugh out of people.

Alex: Oh really? Wow.

Carl: And there was one time when some Marvel executives on the 11th floor were deciding that some people were coming in too late, and Archie never came in super early. But you know, it’s hard to think of anybody who worked harder than Archie. So, I think it was supposed to be like you had to be in by 9:30 and the carrot was like, if you came in by 9:30, there’d be bagels or something like this, but if you didn’t, you know, you’d be in trouble or whatever. So everybody knowing that Archie often didn’t come in until after 10:00 where it’s like, you know, worried about, you know, what was going to happen. And so they set up a place where you had the bagels and all that, not too far outside of Archie’s office. And so we’re all sitting there and eating bagels and all that and watching the clock and a little bit after 10:00, you know, Archie hasn’t shown up yet and everybody’s worried what’s going to happen. And the door opens and Archie comes out in his pajamas and stretches and everybody starts howling with laughter. He got in super early that day just to pull that joke off.

Jim: That’s funny.

Carl: But that’s the kind of stuff he’d do.

Alex: Yeah.

Carl: Just a great guy.

Alex: Yeah, that’s great. So then, so you worked on the Epic Illustrated Lasts of the Dragons. How did that transition into joining Marvel’s editorial staff in 1983?

Carl: Well, one of the things that was happening simultaneously with getting some of this work was that there was a great amount of social interactivity in the comics professional field at that time in New York. Neil Adams would have these first Friday parties at his apartment where on the first Friday of every month any professional could come over to his place for a party and everybody got to know each other there from all the companies, including at that time Archie Comics was still in, in the area.

Carl: And then during the warmer weather months, every Sunday in Central Park, there was an all day long comics industry volleyball game that was going on that, you know, people from all over came in to play those things. We’d often play for 10 hours straight. It was great and I got to know a lot of people there, including Jim Shooter who was editor in chief at the time at Marvel.

Jim: He must’ve been a great volleyball player. I mean just from the-

Carl: Well, he was very intimidating and I, I think one of the things that might’ve been, I might be just projecting this, but one of the things that kind of impressed him was that, you know, most people when he was jumping up in the front line to spike, they would like, you know, try and dig an air raid shelter or something. They wanted no part of that, but I’d go up there and try and block it. And a few times when it was my turn to spike it and he was facing me, I’d go up like I was going to bash it and just slightly tap it so it rolled down the other side of the net. So I think he thought that was pretty clever, but I couldn’t pull that trick too many times.

Alex: Right.

Carl: But he, Al Milgrom, in early ’83, Al Milgrom was planning to leave the editorial staff and go freelance and Shooter didn’t feel any of the current crop of assistants were quite ready to promote. So he was asking around other professionals to see if they could recommend somebody that he pull in from the outside. And he went out to dinner one night with Bill Sienkiewicz who I had been friends with for a couple of years. And I’d never even thought about being an editor before and certainly hadn’t discussed anything like that with Bill, but Bill popped my name into the hat, and what little work Shooter had seen of mine he’d been impressed with because he knew I liked, you know, good clear, compelling visual story telling. I didn’t like confusing the reader. I liked enlightening the reader. And he also knew that if I was given solid feedback on something that I was more than happy to, to make the work better by changing it.

Alex: I see.

Carl: I wasn’t a prima donna saying it’s, you know, my way or the highway about everything.

Alex: Right.

Carl: And so I got a call from Shooter out of the blue and I decided to go for it. And I ended up beginning at the start, pretty much of 1983 being on the editorial staff and Milgrom fortunately stayed on for another week while I was there to help me get my feet under me. And I was also fortunate to inherit his assistant editor at the time, Ann Nocenti, who knew how that office was running. So I basically took over all the titles Alan was doing at the time with the exception of Marvel Fanfare, which he kept editing on a freelance basis out of my office.

Alex: No, that’s cool. So then you got along with Shooter, it sounds like, in the early ’80s?

Carl: Yeah, in the early ’80s, like before I got on staff too. I mean, you know, whenever I met him in social, you know, settings and all that, we got along just fine. And when I got to Marvel we generally got along pretty well. There was a one strange major incident where we did not get along, but I managed to, you know, kind of put that, locked that in the back closet somewhere, and just forge forward until things are getting more nuts in the, in the latter part of his reign.

Alex: Yeah.

Carl: But I, one of the things that kind of struck me is that I would occasionally be talking to some of the other editors and they’d, you know, really have problems with Shooter. And at that point I’d had no problems with him and I couldn’t figure out why until a while later I realized that those people who had started out at Marvel when Shooter was there that, you know, started as interns and maybe became assistant editors and eventually became editors and so on. In his mind, he seemed to see them as whatever they came in on, as that intern or assistant editor.

Alex: Oh, okay.

Carl: And it didn’t matter how long they’ve been there, how much they’d accomplished, he still saw them as this, you know, kind of clueless wonder that he had to mold and guide. Whereas people that had had success outside of Marvel, like when he hired Milgrom and Hama and Louise Simonson from you know, other publishers or Denny, and obviously Archie, they, he saw them more as peers and he, since I had been working at an ad agency before he hired me, he for some reason he put me in that category of someone who had had success elsewhere, and therefore he saw that more as a peer. And if he had the same issue he needed to talk to about, you know, with me or somebody else he’d hired from outside, he talked to them more like peer to peer having a discussion about a point of contention. Whereas if it was with one of the people that had been raised in house, he was basically brow beating them.

Alex: Wow.

Carl: And I didn’t really realize that or find that out till later. So that’s, that was an interesting thing to discover about this guy’s personality.

Alex: That’s interesting.

Carl: That he treated different people differently.

Jim: Yeah, that’s really insightful. I had not heard that before.

Alex: So basically he would kind of go Mort Weisinger on them, in a way.

Carl: I guess. I don’t know. I mean, Weisinger sounds like, you know, he was Shooter cubed. But I don’t, I don’t know. But you know, Jim, Jim was a strange one. Neal Adams and Jim Shooter are both amongst the most complex and perplexing personalities encountered I in the comics business. They both done tremendous things that are, are great and good and generous, and they’ve both done things that are the exact opposite. And I, for the life of me, I can’t figure out the rhyme or reason about what they do when.

Alex: Yeah. And these are kind of like alpha male types who understand storytelling, but then come with a lot of like plus some, you know, you hear polarizing things sometimes.

Carl: Yeah. They’re, they’re very polarizing figures in a lot of ways. But there’s also a lot of us that have seen both sides of them and just can’t figure out what tips the scales or which way they’re going to react about something sometimes. I’m sure in their minds they’ve got it all sorted out and everything makes perfect logical sense. But for the rest of us, rest of us mere mortals, that can be confusing.

Alex: Yeah, it’s still confusing for us. Yeah. So you know, going to your editing, you actually started out real strong. You edited FF Annual 17, Fantastic Four 258. These are John Byrne Fantastic Four issues. How was editing John Byrne?

Carl: Well, I didn’t do a lot of actual editing on him because both of those I think had been started under Al’s reign and I just kind of took them over in the midst of production. And I always got along just fine with John but I could see that there was a potential for some issues down the road because I saw what he was turning in for the next batch of plots and he liked just basically turning in one or two sentences for each issue. And back then what Marvel would do is they would pay a third of the writing rate for the plot and two thirds for when the final script came in, because almost everybody worked the Marvel method back then, which meant the artists worked from a plot and then the, the finish pencils went to the writer to do the final script based on the pencil.

Carl: And so I was a little concerned that I felt that I was going to have to talk to John about getting more out of, particularly since, I think he has a brilliant story mind, but occasionally some of the stories, the endings felt unsatisfying. They had these deus ex machina things, if I remember, I might not be remembering right. But that, that FF annual, it’s like it had to do with the Skrull, and Skrull milk from Skrull cattle or some strange, interesting thing. But, and then in the end, it all got fixed because Reed came up with some spray and sprayed everything. And I just felt that was so disappointing.

Alex: Right.

Carl: So, I felt that-

Alex: Yeah, a lot of his endings are, are kind of like that actually. That’s interesting. I never thought about that.

Carl: Well, the impression I got was that he comes up with these really interesting concepts and figures, you know, he’s going to write them and then you know, they’ll kind of write themselves and they’ll come up to an ending. And sometimes that works for some people and sometimes it doesn’t. You end up with sort of a, you know, things kind of fizzle out or you have to come up some deus ex machina thing to try and pull it all together. And you know, sometimes he was just so spot on, the stuff was brilliant, and other times it kind of fell flat at the end. And I wanted to try and keep that more consistent. So I was gearing up to try and talk to him about writing a more substantial plots and that had the ending figured out before he started diving into them. And I knew that, that there was a good chance that it was not going to go over well and we were going to end up having disagreements on that.

Carl: But then Shooter said that he was up for, you know, expanding the line and trying new things. And I’d had a whole bunch of stuff that I’d been thinking about doing and another new relatively new editor up there, Bob Budiansky, he needed some titles to fill out his roster. So I kind of gave up the FF and The Thing, that little FF franchise, to Bob in order to get space to do my, the new projects I wanted to do. Also, Louise Simonson had pitched Power Pack to me.

Alex: Right.

Carl: And I wanted to edit that as well. But I had ideas for Alien Legion, Shadow Masters, Amazing High Adventure and, and some other things, Spellbound. And also initially I was going to think I was going to edit Long Shot, Ann Nocenti had come up with the basic concept for that and I teamed her up with Art Adams, who I discovered my first day on the job in the pile of unanswered submissions.

Alex: Right. Yeah. You discovered a lot of people. Yeah.

Carl: Yeah. Yeah, that was one of the big pluses of that job was discovering and mentoring a lot of the talent that went on to have great careers. And it’s very gratifying.

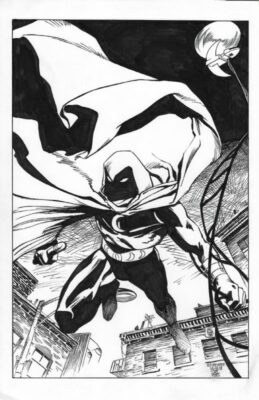

Alex: You also edited Defenders, Hulk, Dr. Strange, Alpha Flight, Moon Knight, and you even inked every now and then. You like you inked a, I saw you inked Moon Knight at some point too.

Carl: Yeah, that was before I was editing. When you were, when you were editing, you technically weren’t supposed to do any of the creative work unless it was part of, you know, your editorial duties. So you couldn’t really freelance the work that you were editing it, it was, that was the way we kept things balanced properly.

Alex: I see. So that inking of Moon Knight was before officially being an editor?

Carl: Yeah. Yeah, that was being, that was when Denny I think was editing the title.

Alex: Okay.

Carl: I got to ink some Kevin Nolan pencils there and I learned a lot doing that, jeez.

Jim: Boy, he’s great.

Carl: Yeah. In fact, when I started editing, I don’t know if you noticed, but Kevin ended up doing a lot of my covers. I’d often do these, for my covers I’d do these quick layouts and give them to the artists to do the finished work. And if you’ve ever looked at Kevin’s old blog site, he’s got a few of the scribbles I sent him.

Alex: Oh, cool.

Carl: And he shows stages of what he turned them out into. So it was great seeing me send off these scribbles and have these amazing pieces of work come back in. And it was, he, at point too, he told that he decided he wanted to not draw anymore. He just wanted to letter. And I told him he was nuts, but that as long as he was being nuts, I’d give him as much lettering as I could. So he ended up re-designing and redesigning a number of my logos.

Alex: Oh, cool.

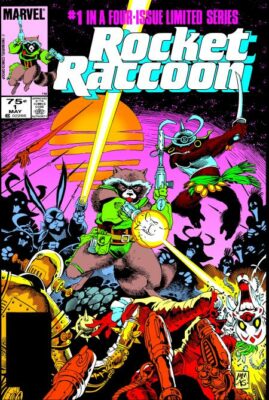

Carl: He designed the original Punisher miniseries logo, Rocket Raccoon, Solomon Kane. When we did, oh when we relaunched Dr. Strange and before that, the Strange Tales on a bit. But so he did, I tried to keep him as busy as I could no matter what. But then thankfully he saw the light of day and started drawing again.

Alex: Started drawing again.

Carl: Yeah.

Alex: Sometimes people need a break from certain things. So then you edited the Rocket, the first Rocket Raccoon mini series. How do you feel Rocket Racoon turned out in the Guardians of the Galaxy movies?’

Carl: Pretty well. I tell people kind of only half jokingly that it took 30 years to be vindicated for you know launching that first miniseries.

Alex: For being there on the first one, yeah.

Carl: Yeah. When I proposed it, a lot of the other editors just laughed, and they said, “What? That’s not going to work.” And that was also Mike Mignola’s first series as a penciler, and up to that point you know, I think he penciled one or two short jobs for Milgrom and Fanfare, Submariner stuff. And he’d send in, when he was sending in his inks, he’d often have these neat little drawings he’d do on the backs of the pages of, you know, weird little characters and monsters and stuff. And Bill Mantlo and I would look at these things and just think, “This stuff’s great. I wish there was an outlet for this kind of stuff here.” And Mantlo proposed doing a Rocket Raccoon mini series. Mantlo was one of the co creators of that property.

Carl: And so we asked Mike to pencil that. So it was his first a Marvel series as a penciler. And after that, since he didn’t really care to draw humans, superheroes that much, I needed a new artist on The Hulk, so I put him on The Hulk and he was there for quite awhile.

© 2020 Comic Book Historians