Comic Book Historians

Don McGregor Career Interview part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

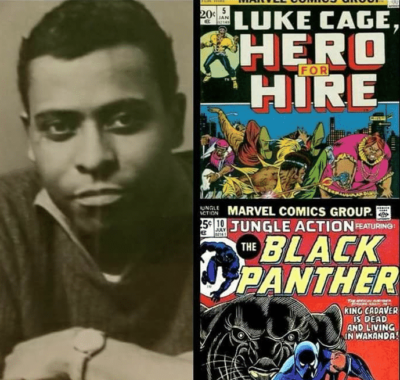

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview comic writer Don McGregor, in the first of a multi-parter on his road to Black Panther, discussing his childhood, jobs out of high school, his first experience with social justice at a Hopalong Cassidy fan meeting, Phil Seuling Comic Convention, introducing himself to Jim Steranko in 1969, heckling Jim Warren into a job, meeting collaborator Billy Graham, and writing the first interracial kiss in newsstand comics. Don also discusses the comics and book writers and artists that influenced his writing as a kid in this kick off episode including Bill Gaines, Al Feldstein, Jim Steranko, and Reed Crandall. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians.

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview comic writer Don McGregor, in the first of a multi-parter on his road to Black Panther, discussing his childhood, jobs out of high school, his first experience with social justice at a Hopalong Cassidy fan meeting, Phil Seuling Comic Convention, introducing himself to Jim Steranko in 1969, heckling Jim Warren into a job, meeting collaborator Billy Graham, and writing the first interracial kiss in newsstand comics. Don also discusses the comics and book writers and artists that influenced his writing as a kid in this kick off episode including Bill Gaines, Al Feldstein, Jim Steranko, and Reed Crandall. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians.

Alex: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians Podcast, with Alex Grand and Jim Thompson. Today we have one of our comic book heroes, famous writer, Don McGregor. Don, Thanks so much for joining us today.

McGregor: Hi guys, how you doing? Thank you for calling.

Jim: I was 12 when Jungle Action came out. And I can’t tell you how excited I am to do this interview.

McGregor: Thank you.

Jim: Your work really, really was important. You and Steve Gerber were super important to me at that early age. So, I just wanted to start by saying, thank you.

McGregor: Well, thank you… I recently was at a convention not too long ago, and a woman came up to me to get one of the Black Panther, Panther vs the Klan books, the one with T’Challa latched to the burning cross. And said she was six years old when she read it. I said, “What did you think of that when you saw it?” I can’t even imagine, at six years old, how would I reacted to that comic, if I saw it at that age. It’s just amazing to me that some of the people who had seen these are very, very young.

Jim: I was 12 to 14, for Panther’s Rage, that was like my prime…

McGregor: Right… Yeah.

Jim: Let’s go to your early days. You were born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1945. What were your circumstances? Were your parents workers? What did they do? That kind of… Just early background stuff.

McGregor: All you need to do is read Ragamuffins, and it’s all there.

Jim: Okay.

[chuckles]

McGregor: Because that’s all based, and in fact I could take you… The places what Gene (Colan) has drawn in there, they’re all based on places and photographs. A lot of it actually, all these years later, still exist. When Li’l Randy is going up Main Street, and he climbs up in a cement wall, he’s pretending to be a cowboy. He’s leaping over a gap in the wall, that leads up to where the person’s house is. And he’s pretending it’s a canyon, he’s leaping his horse over and everything.

All of that is still there. The firehouse, I don’t think the store where I actually first saw comics is still there.

McGregor: But that story, actually is exactly how I first saw comic books. My mom would cross me across Main Street to go to Kindergarten. And I was supposed to stay. I wasn’t supposed to go back across Main Street. Eventually, if you’ve read Ragamuffins, you’d know I do and I get hit by a truck, But that’s another story [chuckle] entirely. But then again, guys, it’s always another story.

But then anyhow, the first time went up that street, and I was supposed to stay, just on the sidewalk. There was a side street where… and I believe the store was called the Charlie Murray’s. And when I went into that store, in those days, they used to have comics up on wires up on the ceiling. And they were hung by metal clips. And they actually, they would stream all around the entire… Like banners, all around the ceiling. The store owner could move the comics, he had a hook that he could grab the wire mesh and pull the comics around until you got to the book, or magazine… but I think it was all comics. I don’t think there was any magazines there. Those were all comics… And I just remember, that was just love at first sight,

Alex: Oh, nice.

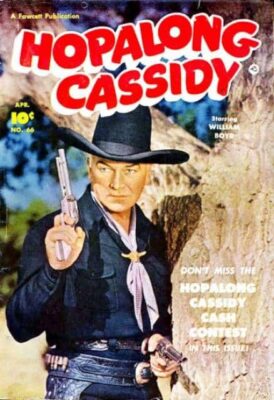

McGregor: I’m five years old, all those colors, all those amazing stuff, and so it probably was my first exposure to comics. The first comic I ever got, I must have been five or six years old… I know it was Hopalong Cassidy #66. And there was nothing I loved more than Hopalong Cassidy, when I was a kid.

And still like I… I got to meet his wife, in later years of being involved in doing conventions with that, Hopalong Cassidy and such. Just, it’s going to be hard for you to imagine the Hopalong Cassidy was as big as Star Wars.

When the Hopalong Cassidy newspaper comic strip premiered open in the Daily News, it was February of 1951, and over a quarter of a million people line 42nd Street.

Alex: Wow.

McGregor: And he was standing outside, just dressed in this Hoppy outfit. His wife Grace was watching from the windows inside the Daily News.

[00:05:01]

And he was out there from 10 in the morning till midnight, in the cold. They hadn’t expected those kind of crowd to appear. And he did not leave, and he came up… They had to bring in firemen… Other people that be… Because they needed security. They didn’t have enough security, and they didn’t expect this to go on that way. And he stayed out until midnight. He was out there from 10 in the morning till midnight.

McGregor: When he came in, Grace said to him, “How could you do that?” He said, “If they can come out to see me, standing in the cold, I could stand there to shake their hand and thank them.” And that’s the kind of guy that William Boyd was.

Alex: Wow, nice,

McGregor: And I never told this story before, I know it’s getting a little side-tracked, and I’ll get back to the comics in a minute. But just to give you an idea why William Boyd is like one of my heroes.

In 1951, William Boyd goes to, I think he’s in Alabama. Pretty sure it’s Alabama. Grace told me this story. He was one of the first people to really merchandise a character. I don’t know whether who it was, Gimbal’s or it was Macy’s, they’re having big showcase there. And everybody was lining up and when Bill get’s there, the lines where set up. You see all these white people in one line and then you see black people in another line. And William Boyd says to manager of the store, “What’s going on here?”

And the manager says, “Well, we’re going to let the white people go in, and then we’ll let the coloreds go in. And William Boyd says, “It’s first come, first served, or I’m leaving. I’m not staying here.” And he broke the race barrier line in 1951 in Alabama. He’s still my hero.

Jim: Wow, that’s great.

McGregor: That story told, you asked about the comic, the reason I brought it up is… I got my first allowance; I got a dime for the week. My dad gives me a dime, and a kiss in the morning. As I go up to school, I stop of at Charlie Murray’s, there’s a Hopalong Cassidy comic. And it’s a Hopalong Cassidy #65, and I said,”Gahh, let me have that.” And he takes the thing down from the rack and I give him my dime.

When my dad comes home, my dad says, “Well, what’d you do with your allowance?” And I says, “Hey, look dad, I got a comic book.” And he goes, “Comic book? You spent your whole allowance on a comic book?”

So, the next week, I get my second dime, and I go… I walk back up and they must have got next month’s Hopalong Cassidy in. Well, you know, I have to have that. Pulled it down from the rack and no, I got my second Hopalong Cassidy. And when my dad comes home that night, and he goes, “So, what did you get with your allowance this week?”

“I got another comic, dad.” I think I lost my allowance for a couple of months then. Then when I started writing comics, I said, “I am writing them now, dad. What are you going to do now?”

[chuckles]

But nobody ever stopped me really, from reading the comics. Because I had a comics collection from… I don’t remember a time, before that, that I didn’t. People didn’t read the comics to me, so somehow, obviously, I could read enough of those comics to get the story. I don’t really recall, because I just always read them. I don’t remember a time… To be honest, I can’t remember a time I can’t read. I know my mom tells me that I always go up to my grandmother’s house. I could go and pick out the records when I was three or four years old, that I wanted to play.

I don’t know if I could read, the thing is, I don’t have a memory of it, I know what she told me. And as with the comics, I do remember… I think it was the measles, that if you get the measles back in those days, they thought you couldn’t read. And one of the comics I read… Because I had a subscription, I’m sure of that. Obviously, I got to read comics. I had a subscription to Dick Tracy from Harvey Comics, by the time I’m seven, or eight. I don’t really remember exactly. But I know it’s before Harvey’s even studied the sense of the Dick Tracy’s scripts.

And I remember getting the measles and my mom having to read Dick Tracy to me. And it’s just not the same, having Dick Tracy read to you as opposed to reading it yourself. That was during Chester Gould’s heyday as a storyteller. He’s just incredible… [inaudible]

Alex: Yeah, he is. You were a fan of his crime stories, basically, right?

McGregor: Well, yeah, and westerns. I think I really like the westerns then and I really like the privates eyes a lot, but the Dick Tracy stuff, I liked a lot. I still do.

Alex: Oh, that’s cool.

McGregor: That’s stuff from 1948 to 1952, I can remember going up to my grandfather’s place, and remember, I was growing up in the State of Rhode Island.

[00:10:11]

My grandfather would get The Sunday News, he didn’t get The Daily News, so I could only see the Sundays. We didn’t go up there all that often, but he stored all of the newspapers that they got. They had a lot of land and a lot of buildings on it. He raised chickens among other things. So, they had a room out there where all of the newspapers were stacked up to the ceiling. And I would go through and try not to topple those scraps on top of myself and try to pull the Sunday News out and read them. So, I only got to read the Sundays for Dick Tracy, and Hopalong Cassidy, and Terry and the Pirates.

I just remember really being captivated by the storytelling and everything, even as a kid. When I got to do a newspaper strip on my own, it was like, that was something a kid in Rhode Island, again, could never have imagined that he would have a chance to do.

I can remember one of the first sequences, and it still stay with me to this day. It was Dick Tracy going up against Crewy Lou, who is obviously, one of the first lesbian characters in comic strips, for sure. And there’s a sequence where she steals Dick Tracy’s police car, not knowing that his baby, Bonny Braids is in the backseat of the car. And they get police chased after Bonny Braids and Bonny Braids… I mean, Crewy Lou doesn’t know that the baby’s in the back, till the baby starts crying. And at one point, Crewy Lou is driving up to the mountains, trying to get away from the helicopters and the police cars chasing her. And the baby’s crying and Crewy Lou reaches back and punches Bonny Braids and goes, “Holy Christmas!” and then we see Crewy Lou abandons the car in the middle of the woods, the baby’s crying and the wolves are coming around the car… I think the Sunday ends with the wolves on top of the car jumping at the windows and everything.

Then the next Sunday is like… Well, there’s Dick Tracy and Sam Ketcham arriving in the woods and they see the car. They get out of the helicopter and they go running up and Dick Tracy throws open the backseat, and you see through the doorway through backseat there’s no Bonny Braids, there’s just torn up backseat springs, where the baby was. And dark splotches where they might be blood. It was like, “Wow”, it really stayed with me, storytelling-wise.

And the same thing with the Hopalong Cassidy, there’s a cliffhanger where Hoppy was driving over on a bridge, and they cut the wires, and he and Topper go plunging into the falls. And so, the next week, he’s like, I don’t know, Hoppy’s someplace else, and you go, “Well, how did the hell did he get out of that?” And as a storyteller, it was already influencing me.

Jim: Were you still reading comics into your teens? And also, when was the first time you wrote a letter to a comics editor or to a letters’ page?

McGregor: I have no memory of that time period really very much. So, I was doing so many things. I know I wrote a lot of them. The only ones I really kind of remember are the ones to S.H.I.E.L.D. I don’t remember the letters specifically, why I remember them particularly, is because I wrote every issue, and I really loved what Steranko was doing, and loved his work.

Jim: So as late as that you were still following comics, in the ‘60s then.

McGregor: If [inaudible] you see the original issues of S.H.I.E.L.D. you will see I’m almost in every issue. [chuckle]

Alex: Oh, cool.

McGregor: I went to one of Phil Seuling’s comic conventions. This is probably 1969, and I guess it’s the first one I went to. I had followed the Steranko S.H.I.E.L.D. s hardbound. I really, really love his stuff. I had the S.H.I.E.L.D. s, and the ones that were in Strange Tales, I guess, it was.

Jim: Strange Tales.

McGregor: I don’t remember. But I have it all in hardbound. And I went to get them… Jim was at that convention and I wanted to get them autographed by him. And so, when I went up to him, to get it signed, I don’t know, we started talking. I handed him the books and he said, “You’re Don McGregor?” And I’m thinking, “How does Jim Steranko know who I am? I said, “Why should Jim know who I am?”

[00:15:01]

And he says, “Listen,” Jim says, “I’m having a party at my hotel room tonight. Don’t let anybody know, I’m going to give you the number. Come down and join us tonight.”

Jim: Wow.

McGregor: So, that’s how I met Jim, and got to be friends with Jim.

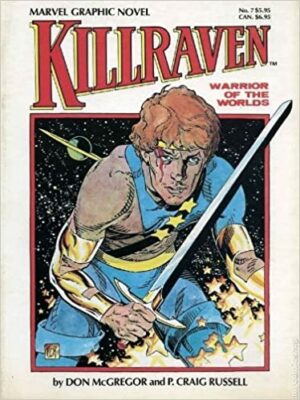

Now, as to why, it was two years later that… When I started writing, say the Black Panther books and Killraven. Not so much the Warren stuff because you got letters for the Warren material, but I was still living in Rhode Island at the time so, when you see letters to your stories, you were seeing them, often, months after you wrote them. Because the stories didn’t appear right away.

But when we were doing the Black Panther stuff, we were so tight on deadline, and because they were series, and because Marvel really had, in those days, the letter spaces were really a part of the package. Especially, if you were a big comics fan. And I got very fortunate that… Thank God for the readers, because Marvel editorial, not very fond of those books, what so ever.

I thank God for the fans because many of them loved the books. And they had an effect on them, and they wrote many, many letters to the books. So, later on when I went to a convention, I met Dean Mullaney, Peter B. Gillis, Mark Gasper, number of people. Since they wrote every book I did, and I wrote, sometimes, 10-paged letters, analyzing what these books were, what they were saying. And what they meant to them, I knew who they were, immediately.

I say, “Hey, you’re Dean Mullaney? Dean, we got to talk.” And so many of my friends, to this day, are people I’ve met through the books. We already have that in common, a shared love of comics. And the fact that they had so much passion for the books. Again, thank God for the fans.

Jim: Yeah, I remember the books that I loved the most were the ones that had the best letter pages too. Because, the people that were writing were the people that had similar sensibilities to me. So, it was your books, it was Tomb of Dracula, it was other things, and it was like I looked forward to the letter pages as much as I did anything else. It was great.

McGregor: When I went to work at Marvel Comics, and one of the things that was probably dismaying to me, and it only speaks to my naivety, at the time. but I really think I thought it was going to be like Stan’s Bullpen Bulletin pages, that the whole panel was… It was everybody urging everybody on to do more and do better. You know, just that very, very positive environment. It was just like any other place, filled with politics, and a lot of back stabbing and a lot of stuff where…

To see writers who were writing about heroes who would then be like trying to climb over the backs of other writers to get titles that they felt were better sellers, or would advance their careers, or get them into a position to do this or that.

Alex: Interesting.

McGregor: I found, it was for me, dismaying. All I want to do is write my stories and leave me alone.

Alex: I see. Yeah, so it was not what you expected.

Jim: Before we get to Marvel… And I want to hear all of that, because that’s fascinating to us. But I wanted to just ask a couple of questions about your beginnings of you as a writer. You worked for the Providence Journal? Was that your first professional writing work?

McGregor: I think the first thing I had published; I had won a poetry thing. It was national. And so it was… In fact, that’s one of the few things I actually can still quote. Because most of the stuff… I could quote other writers’ lines to you, not my own.

Other people tell me, “Don, do you remember you wrote this?” and they will know that line because it spoke very directly to them. Pretty much, I’m not, going back over my own books, because I’m in onto my next project. And every project just demands its own particular research, focus on what that book is about and developing the themes of it, and characters, and some of the books more than others. If someone asks any questions about them or there’s some other project that’s been done at a later point in time, and I’ve got to go back.

I know when I went back to do the Killraven graphic novel with Craig (Russell). I think that was the first time had gone back to the stories. And I didn’t actually read all the stories. I actually… If I was doing an Old Skull scene, I just read his scenes to make sure I had his voice and everything I had written about him.

[00:20:04]

And I had also, wisely, in earlier issues, done… For me, wisely, done character histories. So, it were pages I actually just go and it would pretty much give me all the information I needed, historically, about the characters to make sure I wasn’t forgetting anything or that I was screwing something up that I have established for the character. I was trying to be very, very careful about that. I’m not saying I never made a mistake, but I sure hope… I was doing everything I could to make sure I didn’t…

Jim: Well, since you brought up other writers, and saying you could quote them, let me ask one final question before moving on to Alex, and Warren Comics. During this early formative period, who were the writers, not comic writers but other writers that were influential in your own style, and in your content?

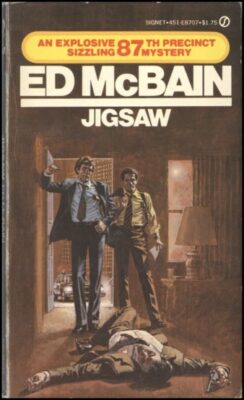

McGregor: Probably, the writer that has the most profound influence on me was Evan Hunter.

Alex: Yeah, exactly.

Jim: Yep.

McGregor: Who is also known as Ed McBain. And I don’t… I’m not a 100% sure of this but I’m pretty sure I’m remembering this right. At the time I was reading both Evan Hunter and Ed McBain, but it was before he had revealed that they were the same person. Because I know I started reading… When I read Buddwing, I don’t think I knew that the Evan Hunter who wrote Buddwing, which was a regular novel, as opposed to a genre piece like 87th Precinct novels were, I don’t think that I knew he was the same writer.

McGregor: You were talking about being a certain age when you read, say the Black Panther or Killraven, and so they had an impact on you. I think that was the kind of way it was with Buddwing for me. It’s all about the guy who wakes up on a park bench one mourning in Central Park, and he doesn’t know who he is. And the book is either a novel about 24 hours in one person’s life, trying to find out who they are, or it’s an entire lifetime.

It’s brilliantly done, so that when you finally realize, “Oh, wait a minute, this can also mean this, and this can also mean that”, and it’s also a novel about New York City. To me, Evan Hunter/Ed McBain was a great New York City writer.

So, even though I was growing up in the State of Rhode Island, reading those books… When I got to New York, I don’t even understand the up and down. I eventually got that, “Oh, yeah, the numbers go this way and they go that way.” If you give the street names, I had no clue where… I don’t understand the horizontal grid, I don’t understand anything in the stories, in real life, the view of that… But I did understand is the city.

He’s the one who taught me about storytelling, and about, not just storytelling but human nature, and about how to explore human characters. I remember Dean Mullaney was saying to me one time, “Wow, Don, I read the book See Them Die. And as I am reading it, I think, boy, this book took Don and blew him away.”

It truly did. It was like one of those books. It had such emotional impact with me and probably… You take that stuff in and I think somehow, subliminally it influences you as a storyteller. I can remember it seeming like, in the book Doll, he had killed Steve Carella. And I remember, being on the bus, my first time coming from New York City back to Rhode Island, on New Year’s Eve. It looked like he’s killed Steve Carella, and he had everybody reacting to Carella’s death. And I remember just having tears streaming down my face. And I’m actually talking out loud in the bus, going, “You son of a bitch, you had no right to kill Steve Carella.”

[chuckle]

I lost it. It was too much… And I think it was the same year that Ian Flemming had died, and I knew there’d be no new James Bond novels coming out. And so, to lose James Bond and Steve Carella within months was just… Probably a little too much for me to take at the time. So, he was one of the writers.

Stirling Silliphant who wrote the Route 66 series. The thing I really got from Stirling was, you could try, every time out. And you could try to knock it out of the ball park. Maybe sometimes, you win, and maybe sometimes you fail, maybe you struck out. But it wasn’t because you weren’t trying. And it wasn’t because you weren’t trying to take the opportunity that you had the chance to reach an audience, to reach people, that you weren’t trying to give them something. And I promise you this, believe me there are a lot of times I just failed miserably. It wasn’t because I wasn’t giving it everything I had at that moment in time.

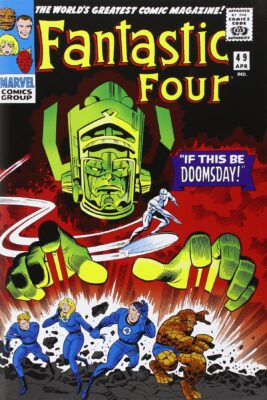

Alex: Were you a fan of Fantastic Four with Kirby and Stan Lee?

Advertisement

[00:25:00]

McGregor: Yeah. Yeah, I’m sure you’ll see letters in there for all the books. I…

Alex: In there also… Yeah, so you have letters there. Okay.

McGregor: Don’t ask me, but I’m sure every once in a while, somebody will post on the internet. I’m sure there are Fantastic Four letters and I’m sure there are Spider-Man letters. I’m sure of that. I know there’s some letters in The Flash because… And this goes to show how little artwork was valued back in those days. One day, a package arrives at the house here where I’m actually living now. And I looked, it’s from DC Comics. I go, “What the heck is this?” It was all the original art to The Flash story that introduced Barry Allen’s parents.

Jim: Wow.

McGregor: And they sent me all the original art for the letter that I had written to The Flash. I had that artwork for years, and unfortunately, who could tell the way things… Never can tell the way things are going to go. In the ‘70s when I was living in New York, I still had all that artwork. And it was at the time when video tape didn’t exist, we were a long way from DVDs and Blu-rays and all that.

In those days, it was really hard… The only way you could see a film or a TV show that you really loved, the only way you could see it again was on 16mm. And a lot of people in comics were film buffs and fans. And I actually traded The Flash artwork, I think for an episode of the Avengers with Diana Rigg. Because I really loved Diana Rigg and Patrick McNee.

Understand that in 1971 or three or whatever it was, to be able to have an episode of the Avengers, complete was… We used to have film nights, like on Friday nights we have people over that would be able to show films. I haven’t watched any of that stuff for 40 years. It’s so much easier now, just throw a disc in. [chuckle] Who knew there’d be a time, okay, you could buy all Diana Rigg Avengers for like 30 bucks.

Alex: Now, your first comic work was with Warren Magazine. Was that the first place that you applied your writing to, as far as the comic world, is Warren Magazine?

McGregor: In those years, I was going to comic conventions, in Phil Seuling’s comic conventions. And when I met Jim Steranko, and went down to his room that night, I met Alex Simmons. And Alex and I became really good friends.

Again, understand that all of us had a love for the same things, we all loved pop culture. So, it wasn’t just comics, but it was TV shows, and it was movies, and it was books. We loved it all. But the one exception would be, a distinction would be, that’s just we’re at the comic book convention. We loved comics and so that kind of was like, put you in a rarer audience than the general audience which still looked down upon comics.

So, it was great when you’re around people who really understood what you love about this comic or that comic… So, when I first met Alex, and I was like doing films, I was shooting stuff on 8mm, back up here in Rhode Island. And I had realized pretty early on, by the time I was 16, 17, somewhere in that time frame, if you wrote the movie, and if you starred in the movie, and if you directed the movie, a couple of things really happen. You always won the fights. And my friends would say, “Don, I can break every bone in your body… what do you mean you’re…” I said, “You and I, we both know that. But see, here in the script, it says I win. And this is how we’re going to do it.”

And I loved doing stunt work, and I could do my own stunts, and fight scenes, and put them into a story. But I was only playing around with that. And even better was, you always got the girl. This is all infinitely preferable to real life and I thought, “Why don’t I just devote my like to this. This is great.”

When I met Alex, again, we both loved to read the Republic serials, we love stunt work, we loved film, and so we started doing films together. Alex would come up from New York and we would do films together. But we also both loved comics. Alex and I were doing a lot of fight scenes together, because I knew that I could trust Alex, and Alex knew that he could trust me. Because when you’re doing stunt work or when you do action, fight scenes, you got to be really careful. A lot of times you’re dealing with people who…

I was doing a stunt sequence, and I had a real machete that I found in some woods in one point in time.

[00:30:02]

So, I was doing a fight scene, and I didn’t know about fake weapons, so we’re using the real… I was working out of the choreography for the fight and I was on the dock over water. The stunt was supposed to be that the bad guy would swing at me with the machete, and I would jump back and this weapon would go past me. And I would come in and grab his arm, and then punch him, and then take him, throw him off the dock into to the water.

We had rehearsed it a number of times, but a lot of times, when the camera starts going, people suddenly put everything into it. And this guy actually kind of like lunged forward, whereas before I was… Good thing I was leaping back because the blade of the machete actually tore through my shirt, went right across my stomach.

Now, fortunately, I was going back so it don’t really… Basically, it left a red line across there. Now, because it’s film, I didn’t stop. I kept doing the stunt… You know, grabs his arm, hit him, throw him in the water and then look… Then I go, “What the fuck are you doing? That’s a real machete! You could have killed me with that thing.”

And I bring that story because with Alex, I think, the one time we were doing a stunt where he was swinging an axe at head, I had to get underneath it, and I knew with Alex, you could do a stunt like that. That we’re both being careful with what we do. If you had one mistake here, and someone’s going to get seriously hurt. So, we started doing our own stunts together.

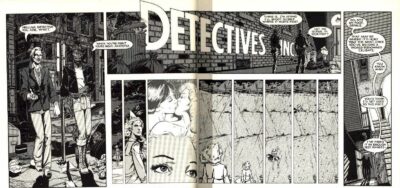

And then I decided … This is how Detectives Inc. actually first get created. They weren’t created for comics, they were created for film, for Alex and I to play in film. And I’d written a screen play called Death Game of Three Dimension. And that was the first Detectives Inc. Then I actually wrote a short story because I was actually taking stories around New York, and I wrote one called Assassins Street. And I was taking that to places like Mike Shayne, Mystery Magazine. I’ve been talking to them, to Mike Shayne people because… I wasn’t trying for comics. I love comics. I didn’t have anything against comics but then I said to Alex, “Hey, why don’t we do our own comic book and go to the comic… We’re going to Phil Seuling’s thing next year, why don’t we do our own comic?” And that became the first Detectives Inc.

Alex: Oh, yeah. Right. Right. I remember because that was your first draft basically, of that. Is that right?

McGregor: We actually did it, Alex. I mean, it was like, all right… We even had deadline problems because Alex had to come up and finish it, days before the convention in New York. He came to Rhode Island and we sat down every day to get it finished and get that book together and collated, and it had a Pepto-Bismol pink cover.

There’s very few copies of that, that I know of that exist. I think Doug Moench had one. I’m not sure if I know of anybody else who actually have copies of the book. I’m sure they do. We finished the book up in time for the convention. This is by 1970?

Alex: Yeah, ’71 at Warren, yeah.

McGregor: If I hadn’t done that, the Warren stuff probably would not have happened. Alex and I went to the Phil Sueling convention that year. We were young guys. We didn’t want to have to sit behind the table to sell the damn book. We wanted to go and have a good time at the convention. In those days, somebody actually would man the table and they would sell other people’s books.

So, we actually, I don’t know… I don’t remember what we had to pay them. They took some kind of percentage, I guess or whatever. And it was worth it for us to do it, and we could get around. I take my Detectives Inc. around and hand it out to people and show what I could do.

It wasn’t like there was an active pursuit like I wasn’t even actually thinking about, “Well, I’m going to be doing comics.” Because at the same time, I was writing stories and I was still filming things. I loved all of it and I was doing it all. So, whatever project I was involved in at any point in time, that’s the one where my focus, and my energy and intent was.

They had panels, as they do today. Jim Warren was on the panel.

Alex: Oh, okay.

McGregor: And as we went to see the panel, I handed out Detectives Inc. to everybody going up on the stage. Because I had realized, even at that point in time, especially when there were panels, if the people weren’t talking, often times, they were scarcely listening to what the other people were saying. [chuckle] It wasn’t that important to them. They were involved in their own thing.

Alex: Yeah.

McGregor: And Jim Warren was up there, and it’s like anytime anybody was speaking, the other people were looking at Detectives Inc. and you can see that Pepto-Bismol pink cover, like anywhere from the audience. Now, and just to go to show that I had no… I don’t recommend that this is a way to go, it shows that I had no plans like this would get me published at Warren Magazines. There was no thought of that at all. Most of the time, anything I’ve said or done, 10 seconds before I sort of did it, I had no idea on what I was going to say or do.

[00:35:18]

Alex and I are sitting in the audience, and Jim Warren is up on panel… And I’ve told the story with Jim Warren present, in one of the last conventions I’d seen him at, this may now be two decades ago. Definitely during the ‘90s, probably. Probably around about the time I was doing Lady Rawhide and Zorro. I think somewhere around that time frame.

For a while, Jim Warren came back, and he was doing a convention in New York. I had met up with Jim. It was the first time I’ve seen Jim for quite a while at that point. And Jim will tell you all these stories are absolutely the way they happened.

At that point in time, Warren was talking about going mail order only with his magazines. And because he was going mail order, he could put content into the stories that you couldn’t do if you were selling in the grocery stores or the mom-and-pop stores, or wherever. It was going to make history. His comic books were going to be the best comics ever. No comics were going to be as good as his. He was doing the best comics and he was doing his Jim Warren launch.

And I raised my hand, and Jim Warren points to me and he goes, “Yeah, what’s your question?” or something like that. I got up and said, “Well, if that’s true Mr. Warren, why’re you publishing the kind of crap you’re publishing?”

[chuckles]

This didn’t go over too well with Jim and he just… He went ballistic up on stage, whatever. Which I don’t blame him, to be honest with you. But when it was over, when the panel was over, Jim Warren came rushing off that panel, he came down and came to where Alex and I were getting up and getting ready to leave.

McGregor: He was like, “Hey, Hotshot!”, which is what he started to call me that weekend. “Hey, Hotshot, come over here.” Then my name became Hotshot, I think, for quite a while, because he was big Terry and the Pirates fan, and he continually referred to me as Hotshot Charlie.

Alex: Hotshot Charlie, good.

McGregor: “Hey, Hotshot, come over here. How dare you ask me a question like that, in a public forum?” or something like that. And I was going, “I think it was an honest question”, or something like that, “I don’t know, I’m 20-something years old. What do I know?” And Jim goes, “Name one story. Name one story I ever did that was crap.”

“Now, I’ll be honest with you Jim”,… Alex, I… There’s not a thing I would do now, because I understand it could have consequences to a person’s career later on… But I wasn’t in the business at the time. I didn’t know anything about that kind of thing… And I named a story. And I still legitimately, to this day, I’m sorry, the story is crap. Okay? I’m not going to tell you what story… But, Jim Warren says, “Oh, yeah? All right. Come with me.”

Alex and I followed Jim, and he goes into… In those days, they used to show movies. They might have been there actually for 24/7, but I don’t want to swear to that. But if they didn’t, they showed them way into the night. Because again, that’s the only way you could see old stuff, was like if you went to some kind of film retrospective. And the comic conventions Phil would have at the time, were showing old movies.

I don’t believe I ever attended any of them because we were always busy doing stuffs, other things, so I was not going to them. But we go in to the darkened room. It’s huge. Huge room. And I can see that Jim is walking down, looking up the aisles… He’s obviously looking for somebody. And eventually, he sees the person, and he motions the person over.

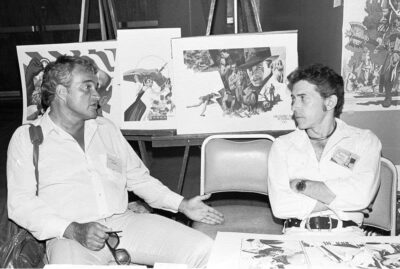

This 6’6” black guy comes out and Jim Warren goes, “Don McGregor, this is Billy Graham. Billy Graham, this is Don McGregor.”

Alex: Oh, wow.

McGregor: “Don McGregor, tell Billy Graham his work is crap.” And because it’s absolutely not true, I said, “I didn’t say the artwork was crap. I said the story was crap.”

[chuckles]

I think he was amazed that I didn’t lose my cool about it, or I didn’t get flustered or rattled, or I don’t know what. I swear to God to you, if I’d gone up to Jim Warren at that convention, and said to Jim Warren, “Geez Jim, I love your books. Your books are the best comics ever. Nobody does comics as good as…” None of what happened after that would have happened.

Alex: Right.

McGregor: It only happened because of the sequence of events that I had just said to you.

Jim Warren actually takes a step back. He says, “I’ll tell you what, Hotshot, play your cards right, and I’ll take you out to dinner tonight.” So, I end up going out to dinner, Alex and I, go out to dinner with Billy, and with Jim.

[00:40:05]

Despite that beginning, Billy Graham, and Alex and I have become very, very, very good friends.

Alex: Oh, wow.

McGregor: I think Billy saw, in Alex and I, that we were younger versions of himself. Like these young guys who just love comics, loved everything, and nothing was impossible, and I think Billy really… This is my interpretation of it, and you could ask Alex what he thought about it but I think that was probably what he enjoyed about it. And we got to be good friends. When I needed a place to stay in New York City, I would come and stay with Billy, up in Harlem, or I would stay with Alex in Spanish Harlem.

So, this has now became a real big influence of my life because it was just opening entirely new worlds for me. Billy took me to see Jeff Jones and to… About that time, Louise Simonson was with Jeff, and they had parties for comics people. I don’t know whether it was once a week or once a month, but Billy was invited, so Billy said, “Come on, Don. We’re going to go.” And that was the first time, sitting around a room filled with people who all loved comics.

So, I got to do a lot of stuff. I had a lot of exposure… Because a lot of white people continue to tell me, “You can’t go up to Harlem at 2 o’clock in the morning. You’re going to get killed, Don…” As it’s always been, it’s white people trying to make you afraid. I don’t care what that was all about.

And later this year, hopefully, we’re still working on the production values. We’re going to re-shoot all of Billy Graham’s artwork for Sabre, An Exploitation of Everything Dear, we’re going to come out, in a deluxe prime, all of Billy’s artwork restored, and it’s in the process. I forgot I owe his granddaughter a letter. I will get to it. I talked to Dean. I have talked with Dean this weekend and it’s one of the things I will get around to doing.

Now, that doesn’t end the Warren’s stories yet. It takes you to the point but, yes, I met Jim Warren, he’s good, and we go out to dinner. And the next day, I was coming to a big room into the convention. I don’t know… The display room, I guess. There was an open section in the beginning, Jim Warren was standing, and he had a painting that was covered. It had a coverlet over it.

Jim says, “Hey, Hotshot, come over here.”

Alex: [chuckle]

McGregor: So, I come walking over and he says, “You really think you’re a Hotshot, don’t you Don.” And I said, “No I don’t.” And I really didn’t. I’m just trying to do the best I can. So, Jim Warren goes, “Okay, I have a Vaughn Bodē painting under here.”

Alex: Oh, wow.

McGregor: “And I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to lift this coverlet up, and I’m going to count down from 10. I’m going to give you 10 seconds, and then when I get to one, I want you to give me a story for this painting.

Jim: Oh, wow. That’s great.

McGregor: And I go, “What?…”, in my head, like, “Uh… Okay”. So, Jim starts, “10, nine, eight, and he’s lifting up the thing there is the Vaughn Bodē painting, and I’m looking at it, and I got nothing.

Alex: [chuckle]

McGregor: “Seven, six, five, four…” And I’m still staring at it like a deer in headlights. “Three, two…” and the one thing I know guys, there’s only one thing I know, I don’t have anything in mind. I had no idea. But know that when he gets to one, I’m going to start talking. And he was, “Two, one…” and I start, “Okay, there’s two guys and…“ And Warren says, “Whoa, Hotshot… I got professional writers,” I’m not going to mention any of their names now, “Who want to do stories. This is a Vaughn Bodē painting, you think I’m going to give it to a nobody like you? Are you kidding me? Get out… you’re not getting a Vaughn Bodē painting.”

So, we had this discussion, and okay, I’m not doing it. Four months later, I get a call from Jim Warren. By that time, I was ready for him, and I had started writing stories… And let’s get this very, very clear, you’re getting $25 a story, and they owned everything. So, if you did an eight-page story for them…

But I got really, really, really spoiled. My editor was Archie Goodwin. And Archie was one of the best people in the business, fair, honest, and anything he told you was to make your story better. That had nothing to do with his own ego, the way he would write the thing was like it was your story. So, I had written a number of stories for them…And you got to send them on a Monday, I think I wrote one eight-pager then I… It’s not an eight-pager, I started doing 10-paged stories, and then I started doing 12-paged stories… And you still got $25 a story, no matter how long it was. So, you can honestly see, I was not in this for the money. Obviously.

[00:45:01]

It was like, “Now, when is this story going to be out? What was the story going to be about? And how can I, you know… What can I do with this, now that I have the chance to tell this story?” Somewhere along the way, I had sold a number of stories, maybe like a half a dozen stories to them, or something. And I got to know Jim, when I was in the city, sometimes I would go work with Jim on the magazine, at night, he was letting me help him do some stuff on the magazine.

I was good friends… Billy was the art director; he was the first black art director in comics. Billy was the art director at the time, so I was seeing Billy. When I would go into the city, I’d either be staying with Billy or I’d be staying with Alex. At that point, I get a call from Jim Warren, he goes, “I’m going to send you the scripts I got from the people who done this Vaughn Bodē painting. And I want you to take one of them and I want you to write the script around somebody else’s script.”

I said, “I’m not interested.”

He goes, “No, Don, I know what I’m paying you. You can’t afford to turn this down. You’re going to be involved with the cover.” I said, “I’m not interested in that. If you want to send me a copy of the painting, so I can look at it and come up with my own story, then I’ll do it. I’ll do that. But don’t send me other people’s scripts, because I’m not reading anybody else’s scripts.”

Alex: Yeah.

McGregor: It wasn’t because I was better than anyone else, I just had no interest in doing it. All I want to do is tell my own stories. I don’t know what would be wrong with that.

So, finally, Jim kind of gave in and said, “Okay, I’m going to send you the painting.” And that ended up being the first story that actually saw print. This is the first story I wrote was the first one that saw print.

And because of Billy… Billy put my name and Tom Sutton’s name on the cover of the magazine. Because creator’s names didn’t, you know, like the artists and writers. They did not get put on the cover of Warren magazines… Yup, Billy ended up doing it. And I didn’t even know the story had been drawn. I’m still living up in Rhode Island, one day, I get a package, and then there’s Creepy magazine, with my name on the cover and then mine is the lead story. Tom Sutton had drawn it. I had not seen any of it before, and Tom did everything I asked for.

Alex: Nice.

McGregor: If I wanted continuity shots, if I wanted the point of view shots, if I wanted a reverse angle shot, and if I wanted it through a sniper scope, whatever it was, Tom did it and more. Archie Goodwin edited it, and man, was I being set up. Boy, I wished that it was always, always going to be this way. The story had to come out like exactly the way I wanted it to come out.

Well, I was really in for a rude awakening but that was down the road.

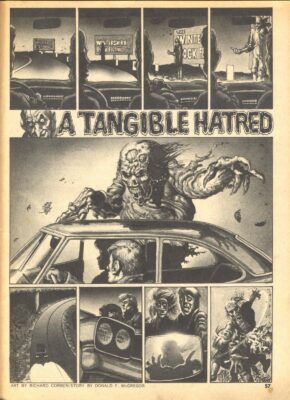

Alex: And just a couple of bullets from the audience, so When Wakes the Dreamer is listed as your first story, but it did not see print until 1973 in Eerie #45. But the one that saw print first was The Fade Away Walk, in Creepy #40 in 1971. You had the first interracial kiss, in Warren’s Creepy #43, 1972, The Men Who Called Him Monster. And in that story, The Men Who Called Him Monster did you get any mail on that? Was there any fan reaction at the time?

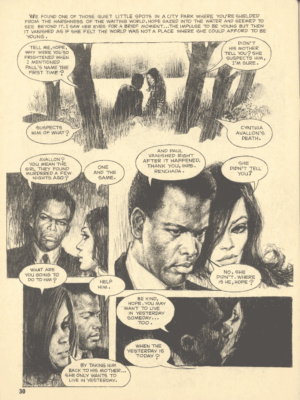

McGregor: Well we have to go back at that a little bit. When that scene was written, I didn’t write an interracial kiss in that scene, that story. It was about a private eye… Plot: private eye who’s looking for a missing teenager. He goes to see the kid’s teenage girlfriend. She’s working at a McDonald’s. And script was drawn overseas by José González, and it looks great. The detective looks like Sidney Poitier.

Alex: Yeah.

McGregor: And he’s asking her about her missing boyfriend and about what happened, and I really knew… Again, you had really tight space in a Warren. You don’t have a lot of room, and so all that scene had to happen in one page. And so, I wanted to try and get as much emotional impact as I could out of it. And my description to the artist for the last panel was, I said, “This is the clincher.” And what I meant was… I’m using an American slang for, “This is the one that should emotionally slam the scene home to the audience.”

The artist reads it and, thinks I mean, “Okay, they kiss.” And they got this passionate kiss. Well it doesn’t make any sense at all. I mean, here’s this older guy and she’s this young girl who is like worried about her boyfriend… like why? What is that scene doing there? But it does make history for being the first interracial kiss in American comics.

Alex: In American comics, yeah.

McGregor: Later on, it’ll happen on purpose, in Killraven.

Advertisement

Alex: You mentioned Tom Sutton, but there was also Richard Corben, illustrated stories of yours, there’s Reed Crandall. So, were you fans of Reed Crandall and Corben at the time?

McGregor: Love Reed Crandall. I was very fortunate; I had an uncle who was a real asshole. He really was terrible. I’m not going to… I’ll try again not to mention any names, He was growing up in the ‘40s.

[00:50:00]

So, at that time, he had really great taste in comics, and when I go up to my grandma’s house, when I went up the attic, I found all his old comics. He had The Little Wise Guys of Charles Biro, Daredevil stuff, a lot of the Reed Crandall military comics, Blackhawk stuff. Unfortunately, mom burned all those comics in about 19… Probably, when I was about 10 or 12 years old. I don’t… I used to tease my mother all the time, and I think it was making my mom feel too bad. At times, I would say, “Mom, if you hadn’t burned those comics…” [chuckle] [inaudible]

Alex: Yeah. In the late ‘50s. Yeah.

McGregor: I had exposure to those comics pretty early on. So, along with the comic strips, which I really dearly loved… I always buy my own comics as well, so a lot of it would have been westerns. I really like the westerns. A lot of exposure to Milton Caniff. I can’t say Caniff had a lot of influence on me in the earlier stuff, because I hadn’t seen enough. When I was doing the Marvel stuff, it’s not really very much Will Eisner-inspired because I hadn’t seen enough Eisner at the time. But there’s a pop culture full circle kind of thing, where when somebody yells, “His”.

I was more influenced by Steranko. All those interior title page designs for Panther’s Rage, and Panther Versus the Klan. I always love that kind of thing when I saw Jim doing it in the S.H.I.E.L.D stuff, and I just took that idea and ran with it, and did my own versions of it. But I do pay homage to it with Malice by Crimson Moonlight, it’s very much inspired by Dark Moon Rise, Hell-Hound Kill! that Steranko did.

Alex: So, were you a fan of the EC Comics?

McGregor: Yeah. Al Feldstein did some incredible things. But I didn’t see a lot of the EC Comics when I was younger. I’m not sure when I had my first exposure. I loved a lot of the EC stuff. I don’t remember where I first got exposure to them, I’m sure when they were reprinting them somewhere, but I don’t remember when that would have been…

One of the first times would have been when I was doing stuff at Warren. Because Warren… I don’t know if Forry Ackerman did it or if Warren had done it, or they both did it together, they did a hard cover. That’s probably my real first exposure. I really love that stuff; I think some of that is so far ahead of its time.

Alex: Yeah.

McGregor: Specially some of the shock, suspense stories as well. Ganges is so far ahead of its time. Outstanding.

Alex: Outstanding.

© 2020 Comic Book Historians