Comic Book Historians

As featured on LEGO.com, Marvel.com, Slugfest, NPR, Wall Street Journal and the Today Show, host & series producer Alex Grand, author of the best seller, Understanding Superhero Comic Books (with various co-hosts Bill Field, David Armstrong, N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., Jim Thompson) and guests engage in a Journalistic Comic Book Historical discussion between professionals, historians and scholars in determining what happened and when in comics, from strips and pulps to the platinum age comic book, through golden, silver, bronze and then toward modern

Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians.

Read Alex Grand's Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland & Company here at: https://a.co/d/2PlsODN

Series directed, produced & edited by Alex Grand

All episodes ©Comic Book Historians LLC.

Comic Book Historians

Scott Shaw! Interview, the king of cartoons part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

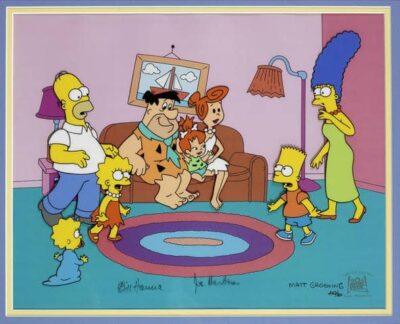

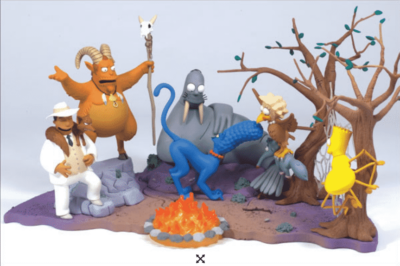

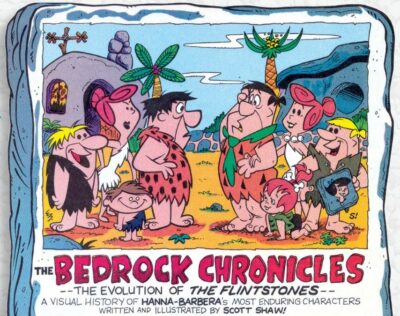

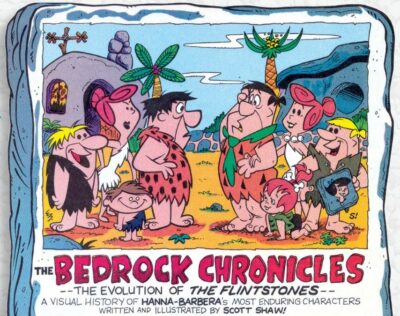

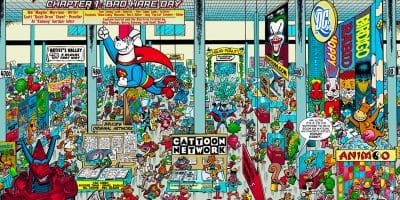

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview animation wizard and cartoonist, Scott Shaw! talking about his involvement in Underground Comics in the late 60s, early 70s, co-creating the San Diego Comic Con, Hanna Barbera Comics, creating and producing Saturday Morning Cartoons like the Flintstones, Muppet Babies, Camp Candy, Ed Grimley, etc, making Saturday Morning Cereal Commercials, contributing to Disney Films, his 40 year career span as a Comic Historian researching Oddball Comics, and his conversations with people like Rod Serling and Chester Gould. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. #ScottShaw #Flintstones #MartinShort #HannaBarbera

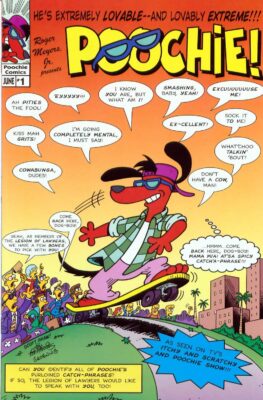

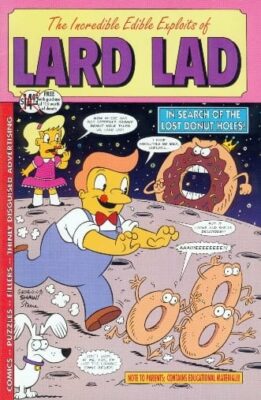

Alex: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians Podcast, with Alex Grand and Jim Thompson. Today we have a very special guest, Mr. Scott Shaw!. Scott has received four Emmy Award Certificates for story direction on Jim Henson’s Muppet Babies, an Eisner Award for his work on Bart Simpson’s Treehouse of Horrors #5 for Best Humor Publication, an Eisner Award for his work on Simpsons Comics 1999 for Best Publication for Young Readers, the San Diego Comic-Con’s Inkpot Award for Outstanding Achievements in Comic Books and Animation, the Humanitas Award for Camp Candy, the Shazam Award for Best Comic Book Humor Art, and a Squiddy Award for Superman & Batman: World’s Funnest. He was nominated for the Eisner Award for a set of Oddball Comics trading cards; Best Comics Related Product. The Reuben Award for Television Animation Division, and the Emmy Award for Outstanding Art Direction.

Scott is a member of the National Cartoonist Society, the Comic Art Professionals Society, and the Animators Guild. Welcome to the show, Scott.

Shaw!: Thank you very much. I’d forgotten I had done all that. Thank you.

[chuckles]

Alex: But it’s a good way to kind of frame what we’re about to dive in to. So, go ahead Jim, and start the early chapter.

Jim: Alright, so what we like to do, Scott, is to go through your earliest life. Where you were you born? When you moved, where ever you moved to? Which we know. A little bit about your interest in comics as a child, and also your family, and just get a sense of who you were when you were born…

I know you were born in 1951, and it was in Queens, New York, which is fairly typical for people we interview. But you didn’t stay there. You moved as a young person; you moved to the West Coast. Talk about your upbringing a little bit.

Shaw!: Okay. Well, both my parents grew up in Central Illinois, in a town called Decatur, Illinois which referred to itself as “The Soybean Capital of the World”. Then my dad joined the Navy while he was a kid, shipped out for boot camp in San Diego. That’s why we wound up in San Diego.

My dad always said that that was the nicest place he’d ever been. Even nicer than Hawaii, where he was shipped out to, and happened to be there during the time of the attack by the Japanese. His ship was capsized by an explosion. He survived. They made him an officer, almost immediately because they had lost a lot of people and they needed smart guys. My dad was a smart guy. He wasn’t an educated man, like I said, he grew up on a farm.

Shaw!: So, the reason I always say all that because that’s why we wound up in New York. My dad was the aid to an admiral. And even before I was born, my parents were living in the servants’ quarters in the mansion that this admiral had been placed in for a while on Long Island.

Anyway, I was born in the Navy Hospital. I guess my dad was re-stationed in San Diego. But knowing my dad, he’d figured out a way to get that all manipulated. He did this to the system all through the war. And I think he just kind of understood how to play things, how to talk to the right people, how to trade favors and stuff. Because he did that the whole time, when I was old enough to notice that he was like the honest Sergeant Bilko.

Jim: [chuckle] Is that possible… I suppose.

Shaw!: Yeah. My dad knew how to get these little favors done so we wound up going out to San Diego, when I was two and a half years old. And I grew up, a white kid, in a Navy town, with a father, who was a Navy officer… Life was pretty good for me.

And in San Diego, with Balboa Park and all these museums, and all these animals, prehistoric stuff, all that, I mean, I was going to the Museum of Natural History for classes when I was five years old. The first day we were there, we’re sitting in the front row and they put a 15 feet boa constrictor across the laps of everyone sitting on the front row.

Jim: So, where you an early reader?

Shaw!: I was an early reader. I was reading by Kindergarten, because like every kid my age, we had subscriptions for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories. It’s funny, I asked my mom, not too long before she died, I said, “I was born in ’51. By ’53, Americans were being told that comic books caused their children to be juvenile delinquents. That point on, there were comic book burnings. I’m sure you saw them on TV. Why were you buying me all these comic books? Were you trying to breed yourself, Doc Savage style, a young criminal?”

And my mom just rolled her eyes and said, “All I know is, you sure seem to need them.” Because I taught myself how to read and draw with comic books. I’ll never forget, I had a Woody Woodpecker Comics. In those days, it was pretty much all funny animals and Dennis the Menace, and Dennis the Menace imitator type books.

[00:05:05]

I’ll never forget, it was the story where Woody Woodpecker had like a little drive-by short orders stand, out in the middle of the dessert, and Buzz Buzzard’s driving by, trying to con him. And he orders this piece of pie, I remember sitting there thinking, that pie is just two triangles and they’re drawn… I didn’t know the word parallel… But it was like, “Oh, and then if I connect the lines here”, it was like I never had a How to Draw book in my life. And I remember, that was the first thing I ever taught myself how to draw. Pretty good, for a fat kid. It was a pie, but it was that sort of information.

Then after a while, by the time I was in third grade, I think… I skipped the fourth grade; I was in an interesting program in California, I was in the first wave of it. It was called the GATE Program; Gifted and (Talented) Education

Jim: Yeah, I was going to ask you about that. You were protecting us from communism, right?

Shaw!: Yeah. They wanted us all to become scientists. Therefore, I never gotten the art classes, even though in the very name of the program was gifted and talented. I, however, always rejected the term talent because I think that’s just what the money guys, the term they use to think we can get paid less.

Alex: Oh, wow. That’s interesting.

Shaw!: “Well, they’re just talented. It’s no more effort for them than going to the bathroom.” That’s a much easier way to not pay us much money.

Jim: We’re going to talk about the comics you were reading, because you’re mentioning mostly funny animal books. Were there other things you were reading too, in terms of comics? Or was it primarily, Dell and Disney and so forth?

Shaw!: Up to a certain point, I’ll never forget, I was five years old. I was in the hospital for my tonsils. And I’ve talked to a number of people online, about this, guys my age. And it seems like a lot of the kids, who were sent to the hospital, they’re own their own, they’re promised ice cream. That’s not nearly enough. We like comics already, but suddenly, comics became our best friends, because we didn’t know any of these other kids. For a nerd, you were kind of hesitant to even introduce yourself.

Suddenly, my dad brings me, what I imagined in my mind to be a towering stack of comics. The most comics I’d ever gotten at one time. It was probably maybe 10 comics. But still, I’ll never forget; I got a Mighty Mouse book, I got a Dennis the Menace book, I got Woody Woodpecker… I mean, you know, the standard kiddie comics, but then in the middle of that was an issue of Superboy. And it was Superboy on the cover, he’s the one-man baseball team. I really didn’t give a damn about sports then, and I even care less about it now. But seeing that cover, with the same guy on at nine different places or 10 different places, whatever it was, that really got my attention.

Jim: Interesting.

Shaw!: I picked up that comic at a show in San Diego not that long ago. And as I read it, it was really eerie, because I realized that was one of the comics, I taught myself how to read because the vocabulary was bigger. As I’m reading it, I’m already remembering what the dialog is in the next panel. So that book must have really had an impact on me. Maybe not to be a superhero artist but certainly in terms of just being able to read something that…

I mean, Mort Weisinger had a lot of tricks in terms of drawing the kids in. Every panel state the same thing in three different ways. But you know what, it worked. He may have been the meanest editor in the history of comics but I think he was a brilliant editor… Outside ripping off his creators. The guy would come in and pitch him a story, and he’d say, “That stinks!” then the next day, “Hey, I’ve got a great idea for you.”

[chuckle]

Alex: Yeah. Plot it to the next guy. Yeah.

Shaw!: Yeah. But in terms of his understanding, what kids would be willing to do to understand these things, and how to help them out, in terms of having the visuals and the words in sync at all times; that’s the whole point of comics, right? The words support the pictures, and the pictures support the words. It made it much easier to teach yourself, I mean, I can imagine.

The last superhero comic I would give to a little kid would be Spidey Super Stories, only because they at least kept the dialog down to a minimum and the story telling will have clarity. But after the point where fans start reading Jim Steranko and thought they were as good as being artsty-fartsy as he was. And I don’t mean that as a slam on Jim, because his stuff holds up great. But from that point on, a lot of people are saying, “Let’s be tricky before we understand how to tell a story”, and it’s just gotten worse from that point on.

Jim: So, in retrospect, looking back at the books you were looking at, are there artists that you think influenced your own work, and artists that you really admired, that you didn’t even realized who they were at the time?

[00:10:09]

Shaw!: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I do kids’ stuff now. Not always but that’s probably where most of the money comes from. And the guys that I loved back then were Sheldon Mayer… Now, I wasn’t even reading Sugar and Spike then I was reading Three Mouseketeers. And I loved Dennis the Menace, especially the big Giants because those were done by Fred Toole and Al Wiseman. And I’d prefer those actually to Craig Fischer’s version. I think those guys… Or at least, I mean, Al Wiseman and Kurt Schaffenberger may be the two finest draftsmen in the history of comics. I mean, I’m sure they weren’t getting top rates for any of that stuff, but they just know themselves out on it. And I understand Hank Ketcham was a real hard guy to work for too.

Jim: Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard as well.

Shaw!: Yeah, I hear it all through the distance… But anyway, those were the big deal for me. Carl Barks, of course. I wound up becoming friends with Carl, years later, and that was a big deal… Let me see… Oh, Little Archie, I really like Little Archie, and Bob Bolling I think is a really overlooked writer. His art is great, but he could write kids’ stuff, kind of like John Stanley; with the eerie understanding of how kids think. But Bob’s stuff had this kind of sorrowful gravitas to it, at times, that I just think still, is brilliant.

Jim: It’s my favorite Archie stuff, it spoke to me… I was born in ’59, and I was reading that stuff. I didn’t discover the Stan Lee stuff until later, just when it’s been re-printed in the last five or six years. But the Bolling stuff, I was reading as a kid, and just loved it.

Shaw!: I used to get beaten up for reading Little Lulu. Boys don’t read Little Lulu.

Jim: Yeah, I got beat up a lot too. [chuckle]

Shaw!: Oh well… None of that stuff happens anymore. Now, the nerd gets laid, are you kidding?

Alex: Yeah. It’s a good time… To be a nerd, I mean. Not that I would know.

[chuckles]

Jim: But it’s true. It is such a different world, than it was when you and I were going through school. Where I was the only one, there’s nobody else, for most of my school. When I would be on a bus as the baseball manager, I would pull out my comics and people would read them but that was the me. I was the only one that actually knew what they were. Me and Squirrel O’Brien.

Shaw!: I used to get beaten up for knowing how to pronounce dinosaur names too.

Jim: Oh, yeah.

Shaw!: The kids were all watching giant dinosaur-like monsters. Unfortunately, it’s way too much like it is now. Knowing stuff can get you beaten up. I mean, I was very, very, very interested in Paleontology as a kid, in not that that science is going to save mankind but…

I was talking to one of my doctors the other day. At the end of the 1959 movie Journey to the Center of the Earth, which has the only lizards as dinosaurs that really looked like dinosaurs in them, because they understood how to shoot them. But at the end, James Mason gives a speech, to the other boy scientists at a college or university, and he gives this very intelligent… I mean, even now you go… He says, “We went to the center of the Earth but because we can’t prove it, it’s up to you to prove that this exists.”

I bought into that my entire life. I mean, just because I didn’t go with Paleontology… A teacher once told me, he said, “You’re not going to go the Gobi Desert, and you’re not going to be running a museum. You’ll probably going to wind up working for an oil company, finding them petroleum deposits.” Almost immediately, I said, “Well, that’s my hobby now.”… Cartooning, they were kind of both, even.

But yeah, dinosaurs and monsters, I mean, I would think that an awful lot of cartoonist my age, that’s kind of where it all started.

Jim: A few weeks ago, we interviewed Bill Stout. Now, you’ve known him for forever, haven’t you?

Shaw!: We met in 1969.

Alex: Yeah, you both have that same West Coast presence too.

Shaw!: [chuckle] What does that mean?

Alex: You guys are West Coast based professionally. And also, you’ve both done underground comics and things. Pretty interesting, and diverse careers.

Shaw!: Yeah, and Bill and I both can draw like Big Daddy Roth.

[chuckle]

I think that Big Daddy Roth thing really was a big deal, though guys our age. Like, “Here, get as wild as you want to be. People like that.”

Alex: So, you’re a Ray Harryhausen fan then?

Shaw!: Oh, yeah. Yeah. I watched The 7th Voyage of Sinbad last night.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome. So, it’s fresh in your mind, yeah.

Shaw!: Singly, I’d never seen it at home on such a big screen. The only sad thing was, the monsters in close-ups, they’re shiny. You can really tell they’re plastic.

[00:15:00]

Jim: Did you go to Ackerman’s house when he was still having people come over?

Shaw!: Many times. That’s where I met Don Glut.

Jim: Ahh, that makes sense.

Shaw!: Yeah, I was friends with those… I’m still friends with Don Glut. I was friends with Bill up to his death. Again, Greg Bear, Dave Clark, John Pound, the guy that did all the Garbage Pail Kids, we all went to high school together, and we’d go up to Forry’s house. We’d usually get one of our moms to bring us.

The first time we went to Forry’s house, this is really unusual… We go to the house, he’s not at the front door, so we go down the long driveway to the back of his house… We thought, “Okay, we’ll knock back here. Maybe he’s in another part of the house.” The back door has been broken into. The window’s been caved in, there’s glass everywhere. And then we realized, we go back out and see, there’s pressbooks laying in the gutters. And we realized, “Holy crap! Forry has been robbed.”

About that time, Forry drives up, and he never even once acts like he thinks we did anything. I mean we were concerned. We weren’t trying to run. I guess Forry has been revealed as being kind of a creepy guy, if you’re a good-looking woman but we only saw… He had no reason not to be nice to us, I think, but he understood that we weren’t responsible.

However, we hung around. He said, “You don’t have to go away.” And the insurance guy shows up. Now, I think I was probably all of 14 or 15 at the time, and Forry, who was a big fan of this kind of artificial language, without any set up at all, starts speaking Esperanto.

[chuckle]

Shaw!: Kind of the weirdest place he’s ever been in his life. I mean, this makes the Tiki Room at Disneyland look like nothing. On top of that, Forry is starting to speak a language that he really has no idea what this is all about.

As a kid, I’m thinking, “Forry is blowing it.” [chuckle] It’s like if he wants his stuff back, he’d better pretend he’s normal. I don’t know how he got through it. I think he finally just reverted to English when he finally realizes this guy wasn’t understanding a thing he was saying. It also kind of proved that maybe Esperanto didn’t work as well as it was intended. Because supposedly, if you knew at least two languages, you can kind of get the gist of things… But this guy was not ready for it.

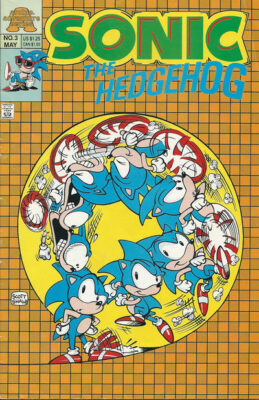

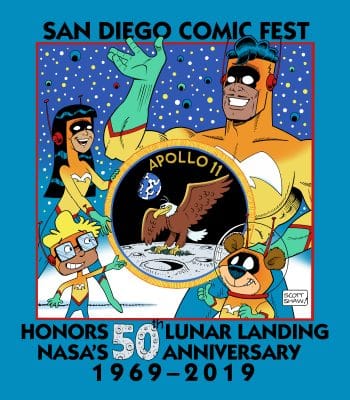

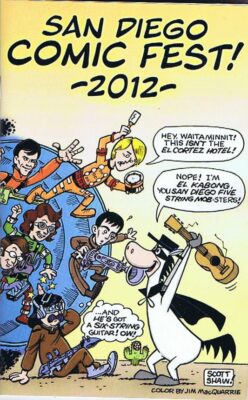

Jim: That’s great. That makes me think of the last time I met you, which was at Comic Fest. And I’m going to go somewhere with this. But I was there with my son, Alex was there. We get a couple of panels. You were there. And you had stepped away from the table, and I was talking to your son, and I was introducing my son Willoughby who was seven years old. And he said, “My dad would love to meet him. Just wait.” And you came back, and I introduced you, and instead of just saying, “Hi Willoughby, and signing something, you had him come around behind the desk with you and sit there with you, and you gave him like a 10-minute art lesson, and step by step on how to draw Sonic.

It was one of my favorite things that’s ever happened at any Comic Convention, and I’ve been to many, many… When I saw that, I’m thinking now, of you talking about going to Ackerman’s house, and I know that Jack Kirby, when you’re a little bit older, that he was very welcoming. It’s a paying back thing, and that’s really important to you, isn’t it?

Shaw!: Yeah. It really is because, I had mentors in San Diego before I already met Jack Kirby. When I was in high school, one of my friends on the school newspaper staff, because I drew comics for the school paper. She set me up with her uncle, who was a local cartoonist named Bernie Lansky. None of you’ve ever he of him but he’s kind of George Lichty style cartoonist. Which, at that time kind of drove me crazy because I like cartooning where the shapes were really obvious. So, stuff like Dennis the Menace, and things like that. I like things like Beetle Bailey. I like stuff where I can teach myself how to draw with it. For example, Ronald Searle, used to just drive me crazy.

Alex: How do you spell his last name?

Shaw!: Searle, S-E-A-R-L-E.

Alex: S-E-A-R-L-E, okay.

Jim: Michael Dooley is a big fan of him, Alex. Writes a lot about him.

Shaw!: Both Gerald Scarfe and Ralph Steadman, with that kind of… What looks certainly at first, just like a nest of lines, and then you go, “Wait a second, this is somebody that’s just drawing organically.” And I remember Searle stuff just disturbed me like crazy. And then I got to a certain point where I went, “Oh, this guy is brilliant.” A lot of the artists that I couldn’t stand when I was a kid, I now really value.

Alex: Yeah, I find I’m doing that too. I like more as I get older.

Shaw!: Yeah, but anyway, back to the San Diego mentors… I would meet with Bernie every Thursday, at the Jewish Community Center, which was on my way home.

[00:20:00]

We’d sit in the little side room, and he’d say, “Okay, show me what you drew this week.” And then, he’d critic the hands, or the gags, or whatever, in a very kind way but kind of, “Do it”. And then another guy, Gene Hazelton, who not coincidentally, was drawing the Flintstones and the Yogi Bear strips at the time, who was considered to be such a great cartoonist that when he was at MGM, he was the only guy that was wasn’t assigned anybody’s unit. Everybody wanted him so he let him float around the different projects, so he could come up with at least a few sketches for them.

He lived in an area in San Diego that he lived right on the edge of the golf course. [chuckle] Just like a lot of the older cartoonists, older than me. He loved to golf. So, he literally had to walk out his back door and he was on the course. And I’d go over there, and he’d drawn everything on tissues first. Because that way, it made them easier to trace. And I still do the same thing. I’d rough something out and then I’d do that, so I could kind of tweak things without getting the paper itself all, you know… He’d give me the tissues at the end of the day. And I still got them somewhere in boxes. I just stored them.

Jim: So, when did comics become something that you thought, “I’m interested in this, and this may be something that I’d want to do.” You came in through Comic Fandom, and the conventions and things. But when you were doing that, did you think you wanted to draw comics for a living?

Shaw!: I knew I wanted to do that since I was five years old… Or be a paleontologist. I think, most cartoonist I know, seem to somehow understand that, from the time they’re a kid. I don’t think their parents understand, and certainly their teachers don’t understand it. It absolutely infuriates me, because I’ll go to schools for Career Day, and they’ll want to have me back and I’ll say, “Well, next time, I’m happy to talk to all the kids, but what I really want to do is talk to the kids who want to be cartoonists.” And they’ll go, “How do we know who those are?”

And I’ll say, “Well, they’re the kids that get in trouble for drawing in class.” They’ll say, “Why should we reward them?”

Alex: [chuckle]

Shaw!: I almost start screaming when I hear that answer, because I think, “You are the shittiest teachers of all if you don’t get that.” But bad teachers seem to think they’re being insulted because they’re not being listened to. What it is, is they don’t get that some kids, if they’ve got a piece of paper in front of them, they just have to put something down on it.

Advertisement

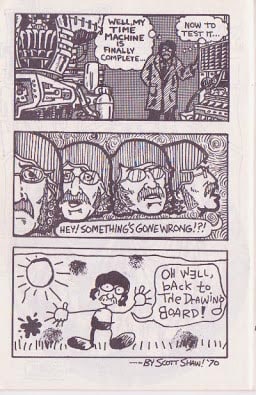

When I was in college, I got a scholarship. So, I thought, well I got to perform. And the first couple of weeks, I was taking notes like a real human. And by the third week, I got cartoons in the margins. By the fifth week, the notes are in the margins. By the eighth week, I’m not going to classes, I’m staying home and drawing the stuff in the school paper.

Alex: Yeah. So, it’s almost like ADD turned into creativity.

Shaw!: Well, there is absolutely no money in it so I don’t think anyone is ever going to do a scientific study, but I think it’s in our DNA. My dad wanted to be a cartoonist… Not a cartoonist. He wanted to be a sign painter. He taught me how to use Speedball pens when I’m about six years old. It’s right there. He liked lettering. He loved lettering. He loved showing me how to letter stuff like the science projects where you’d have to have the little display in the classroom or in the auditorium and some place, he’d say, “You’ve got to make this stuff legible.”

He wasn’t away that much, like I said, he knew how to kind of manage where he was stationed while he was in the Navy. After he stopped being in the Navy, he went to the San Diego Zoo, and they don’t move that so he had a permanent job there. He liked to paint by numbers when he was alive.

At the time, I was, “Oh, that’s my dad.” Then he also like to make these very ornate Christmas decorations for the roof of our house. And then, some of his buddies came out for his funeral and said, “Ah, we heard you’re an artist. You know, your old man wanted to be an artist too.” But my dad never said anything directly to me though. I had heroes at a very early age, and I don’t think he wanted to try to compete with Dr Seuss, and Big Daddy Roth, and Jack Kirby.

Jim: It’s funny though, how it works. When I’m in court, probably a thousand times, I’d been sitting there while the judge is talking, and people are objecting, and I’m drawing pictures of the judge or I’m drawing just cartoon people. And my client, who’s facing whether he’s going to have custody of his son or not turns and says, “Hey, that’s pretty good.” While the thing’s going on.

Shaw!: [chuckle] You better watch out. If the judge knows it’s what you’re doing, he may have the clerk come over and say, “I want to see what are those that has you so interested young man.”

Alex: Yeah, he’s going to get a ruler and slap your hand with it.

[chuckle]

Before we go into the beginning of you comics, I just want to go through like a quick professional chronology. Because in the ‘70s you were doing underground comics, as well as helping co-create the San Diego Comic-Con, with people like Shel Dorf, Ken Krueger. Then in ’78, there was some involvement in Hanna-Barbera Comics, which appear to be a gateway into actually working in animation in the ‘80s.

[00:25:05]

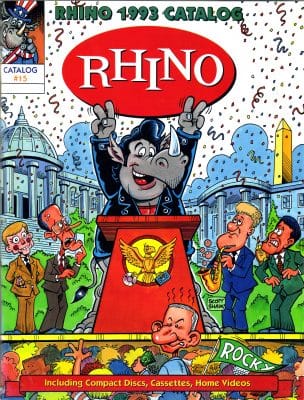

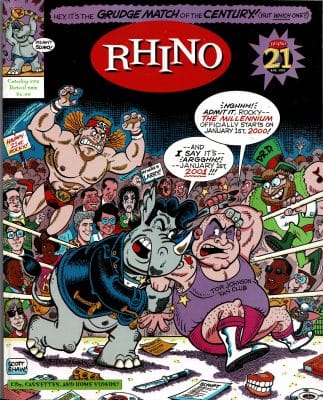

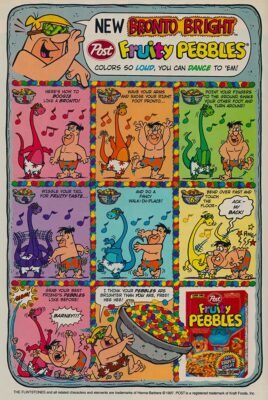

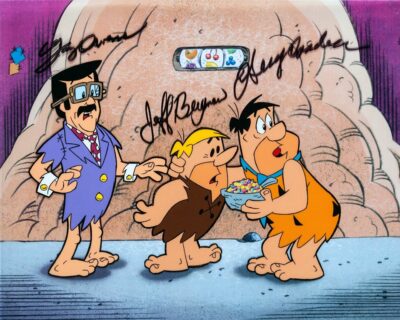

Alex: And a lot of the stuff that I watched as a kid, may have your finger prints all over, like the Muppet Babies, Popeye and Son, and things like that. A lot of the Saturday morning cartoons used to have commercial, like cereal commercials. And then in the ‘90s, you’re basically doing commercials like the Flintstones cereal type things, that I remember, I was eating that cereal because of those commercials. And the advertising goes to the 2000s, and then you start doing actually, stuff with Disney in the 2000s. And then the Oddball Comics as a historian, that’s more of the recent stuff of over the past like 10 years or so.

Shaw!: I’d been doing Oddball Comics for 40 years.

Alex: Actually, it’s been going on even before the comic book resources stuff that you were doing then.

Shaw!: Long before that. Yeah.

Alex: Oh, okay, that’s awesome.

Shaw!: Not to correct yourself, but the interesting thing is. All these things kind of melded into each other. My dad once told me, and it’s been the best advise that I ever had. He said, “Learn to put yourself in the right place, at the right time.”

And the comic, I was always working for the school paper, so that gave me the idea how my work looked in print. By the time I was doing stuff for underground comics, I was also doing advertising and promotional work for a lot of local businesses. Not that many, not enough to support myself. I still had a job. But my job was at the San Diego City Schools, Instructional Media Center, where they kept all the text books and books that were checked out to the kids, all over town.

So, we were expected to file books or unpack books, or whatever. I got that done in about an hour, everybody else were retired Navy chiefs who were like stretching it out for the whole day. Shooting a bowl with their buddies. I’d get it done, and then I go back and reread every children’s books in the library. Because I thought sooner or later, I’m going to be doing children’s material.

Then I moved to LA, and I got a job. Again, I’m not getting enough job cartooning to support myself. I went to LA, at one point, with the ad agencies and studios, and everybody was nice to me and said, “You’re just not ready.” So, I thought, “Okay.”

A year later, I thought, “Okay, if I’m up there, I’ve got a better shot.” I had friends that owned a comic book store about a mile away from Hanna-Barbera. I thought, “Well, that’s the place to meet people from Hanna-Barbera.” I never wanted to work for Disney. I always wanted to work for Hanna-Barbera or Jay Ward. I actually had a job offer to work at Jay Ward when I was in 11th grade. But my parents said, “We’re not going to move to LA for you to take on a free job.” But they were doing George of the Jungle at the time, which I would have killed to have worked on.

Jim: Oh, wow! How did they come to you?

Shaw!: I never got any art classes because they wouldn’t let me have them because of the GATE Program. But they would let me do teacher’s assistants, because my counselor made it clear, the only way she thought that I ever would have a job is as a teacher, not as a cartoonist. She said, “You could do that on your spare time”. And I was old enough to say, “Look, I know teachers don’t have spare time. Don’t feed me that crap.” I didn’t say it that way, but I made it really clear, “No, I will be only be a teacher, only as a last resort.” Because I had other plans. I figured, if I couldn’t make it as a cartoonist, I wrote well, so I’d be a journalist. I like working on the newspaper when I was a student.

So, anyway, I was working for this teacher, and she was the ex-wife of a guy that worked at Jay Ward. Years later, he was one of the directors on Yellow Submarine, which I didn’t know. I wish I could have because that’s my favorite feature film… She sent him my sketchbooks, while he was directing at Jay Ward. And they came back and they said, “If you can come in here, we’d like you to be an intern. “

This was when they were also starting to do a lot of Captain Crunch commercials. That was something I always had my eye on too, because I realized, while Hanna-Barbera and Jay Ward are good studios but I like the animations in commercials better than anything, because they’re different all the time.

Anyway, I wound up working for my junior high paper, and then my high school paper. I won a lot of awards for the high school stuff. But then, one day, I went in to pick up the art for the strip that I’d won like some state award, and they said, “Well, we just gave it away. Somebody came in and asked for the original, so we just gave it to him.” So, I kind of hit seven on the anger scale. And then I went over to pick up some comics I’d loaned to one of my art teachers, I finally was getting a few art classes, and all those comics seemed to have disappeared. The ones that were his favorite artist Rick Griffin like the style, they were missing.

And I just said, “Screw it, I’m not learning anything here. I’m better of…” I wasn’t getting enough jobs to support myself, but I was getting enough to kind of reassure me that… I may have not known what I was doing, but I was kind of bullshitting enough people that they thought I knew what I was doing.

Alex: Yeah, sometimes, that’s all you need.

Shaw!: Yeah, so I dropped out of college in my senior year.

[00:30:00]

It wasn’t a full scholarship so my parents were paying for the last couple of years… I still feel bad about that, but too late. But I moved back to San Diego. I was going to Cal State Fullerton by this time.

Jim: Oh, my wife teaches there. She’s a Professor in Film and Television there. Did you like it? I mean, besides dropping out of it?

Shaw!: Oh, I absolutely loathed Orange County, are you kidding? I was getting stopped by the cops all the time. And frankly, growing up in San Diego… I mean, in San Diego, you can go from the mountains to the water. Orange County, the only way you know where you are is what the nearest mall is called. Everything looks the same down there. At least it did, back then. And because it was so dull, all the local kids, their goal was just to get as loaded as possible on anything they could find on the weekends. It was really a grim place to be.

Alex: Ha! Like crazy glue or something, huh?

Shaw!: Yeah. I mean, believe me, I was getting stoned a lot of the time. But I mean, I was kind of like the most restrained guy there. It was such a bad scene and I didn’t like it. But it may be different now… I hear now, it’s not even run by republicans so that’s kind of interesting.

Jim: It changed just recently. I don’t know if it’ll stick or not.

Shaw!: I think Bakersfield now has that reputation.

Jim: So, you moved back to San Diego.

Shaw!: Yeah, I moved back to San Diego, and worked at that Instructional Media Center, where I could bone up on all these books, and then I moved up to the comic book store. I had enough people from comic books… That’s where I became friends with Roy Thomas. That’s where I became friends with Steve Gerber. A lot of guys from Hanna-Barbera that wound up becoming my friends, to get in there. And of course, I already knew Mark Evanier, I met him at Jack Kirby’s house in 1970.

By that time, Mark was working for Western Publishing, and the former editor of Western, a guy named Chase Craig was an outstanding, nice, supportive editor to bring in a young kid like me. Mark suggested me, and he hired me as an inker. That’s when I started working on those Marvel-Hanna-Barbera comics.

Alex: Okay. Now, we’re talking like 1978 or so.

Shaw!: Yeah. Yeah.

Jim: Let’s go back in time. Because I want to go back to your very first underground stuff, and how that got picked up. That was Gory Stories Quarterly? Is that your first comic professional work?

Shaw!: Yup, that was the first time anyone paid me for my artwork in a comic book. And that was published by Ken Krueger, and that book was John Pound, my friend from high school. He was doing comics and he was doing painted book covers and illustrations, magazine covers. Then he was doing all those Garbage Pail Kids and stuff.

Alex: I love those. I have every single one of those, still. I love Garbage Pail Kids.

Shaw!: I just art direct a video game about Garbage Pail Kids.

Alex: Oh, yeah. That’s cool.

Shaw!: We animate the actual cards.

Alex: Oh, that’s awesome.

Shaw!: Yes. They don’t look crummy like the TV show.

Alex: Uh-hmm, yeah.

Shaw!: I was the only one on that team that remembered the show, and I said, “No, we’re not animating it traditionally.

Anyway, John and I were both in Gory Stories, which was our first comic, and frankly, I being a hippie, a lot more than John was, because he was staying at home and teaching himself how to draw. And the difference in our abilities just rather mark it in that comic. But you know, it’s still ok, the main thing was it got us both out there.

Ken was actually somebody who was also integral to Comic-Con. Because, when I was going to Cal-Western on that scholarship, the nearest area of San Diego with any real stores in it was Pacific Beach, was the hippie town in San Diego and still is. The main drag there, here I go in, it’s a science fiction bookstore, and Ken runs it.

What I didn’t know is, in the back, it was porno store, and that’s how he paid the bills, to sell science fiction. In fact, Ken has told me, he had 14 different bookstores over the years. And quite honestly, as one of the founders, Ken knew how to sign contracts, what to point out, what to see you got to change… This is kind of admiration, having been an underground cartoonist therefore a bit of an outlaw myself. Ken knew how to stay ahead of the cops.

And yet, at Comic-Con, I think that may have been the first one at the El Cortez, but it may have been earlier than that. Somebody stole somebody’s comic, and they were like, “What to do?” And Ken yelled, “Call the cops!” And they got the police there, and they arrested this guy for stealing a rare comic book. Yeah, it probably cost 40 bucks… But still.

[chuckle]

Nobody else there even understood that, “Hey, this is a real crime. This isn’t just high school mischief.”

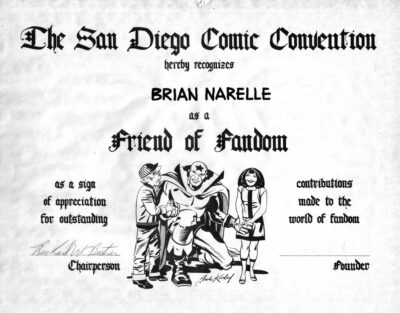

Alex: You helped kind of form that first San Diego Comic- Con, with Dorf, and Krueger, before you published, or were paid to do comic work. Like, although you were artistic and doing artistic things, you’re actually kind of a fan, that then two years after that, then you did your first comics work that was paid for.

Shaw!: Sure, because I was doing stuff in fanzines.

[00:35:00]

And from the stuff I sent you, I don’t know if you could tell, but there were kind of two groups – the collectors and dealers. The other guy you haven’t mentioned that was essential to Comic-Con, I was talking about Richard (Alf) and Ken Krueger to people for years, and finally, everybody agreed, they were as much co-founders as the other guy who named himself co-founder.

Anyway, Richard was a comic book dealer. He was about a year younger than me and he had money. He was very successful. He advertised in Marvel, and I don’t think DC was taking that kind of ads then, and he loaned the Con, I believe $2500, to start that first one day show. Yeah, he put up the money and he was the first chairman too. And a very sweet, smart guy.

Alex: What’s his name? Richard what?

Shaw!: Richard Alf. And he also had the first comic book store in San Diego, called Comic Kingdom, which was really a terrific shop. And all of the shops were kind of like hash bins or something too, everybody would go in the backroom to get stoned. I can’t believe they were never raided.

Jim: After you did Gory Stories, what where the next things? When did you start doing work for some of the other publishers; Kitchen Sink and so forth?

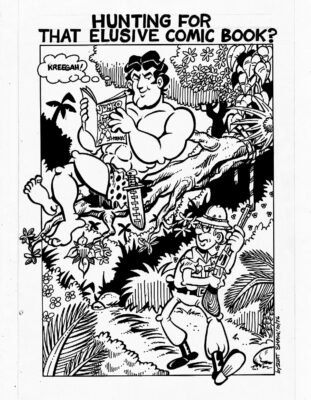

Shaw!: Almost immediately. Then I got some gig from a little, almost a fanzine, but they were trying to kind of cloak it as an underground comic, and I don’t came upon a copy but it was, ARC was the title. I don’t even remember what it stood for. I did a thing called Jones of the Jungle, which was kind of a George of the Jungle thing except it was an executive trying to run the jungle like a business, like a corporation.

Then I started getting other little underground things. I think Savage Tales, I did something for my friends at Simon and Siegel. I think that was a Rip Off … No, Last Gasp. And I mean, it just kind of started spreading out from there.

Jim: Were you doing the same kind of things as some of the others or was your work standing out because of your interest in your roots in animal stuff and the stuff that you liked from early on in comics?

Shaw!: Well, my underground comics were pretty mild. I didn’t do a lot of sex stuff in them. I don’t think I ever did the sex stuff, there, or in my life. I also just didn’t want to get too political. It was more to just goofy stuff. The thing I done that was the most offensive was, I did a poster for Jack Kirby, about a monster with a giant shlong. [chuckle] That was rather embarrassing. I didn’t send you a photo of that.

Jim: And was he uncomfortable with that or was he okay?

Shaw!: Well, he was okay in the long run. But at the time, he was pretty aghast. Because one of my friends… I didn’t tell Jack this, but I didn’t bring him the artwork, I brought him a printed poster. And it was a take-off on an issue of Strange Tales cover. It was now Deranged Tales, a monster who says no human can beat me, and of course I changed it.

Alex: Right. Like one of those monsters’ books that Kirby kind of did. What are those names? Like Goomba and things like that?

[chuckles]

Jim: Not sure it was Goomba. [chuckles]

Shaw!: At Charlton it was Goomba.

Alex: Yeah, Charlton. Sure

[laughs]

Shaw!: When Jack looked at this thing, he was kind of at a loss for words. And I said, “Here Jack, this is for you.” And even down the corner, it was printed, “In honor of Jack Kirby” Because I had heard that Jack had told me, when I first met him, I told him I was doing underground comics and he said, “I like underground comics.” I thought, he meant he liked to read them. No, he meant he liked the fact that people will own their own stuff. They were $50 a page and owning it, was not a page rate in 1970. And there was no house style, everybody could draw the way they wanted.

I thought he just like sitting down with a good issue of Zap Comics. So, I completely misread him because he was so cooler than my dad, I figured, “Well, maybe he’s this cool.”

Alex: Yeah, the monster shlong, maybe it will work.

Jim: You named your son Kirby, so I assume Kirby was incredibly important to you. Can you talk a little about that? Was it his work? Or was it your relationship that prompted that?

Shaw!: It was definitely my relationship but I wouldn’t have really cared that much about him if it wasn’t the work. I think, I first saw Jack’s stuff in that Secret Origins Giant, they reprinted a chapter of his first Challengers of the Unknown. That pretty much fascinated me. Then about the same time, at the same place I bought that comic, in fact, I saw, Sporr, the thing that grew, on the covers of Tales of Suspense #11… And, “Mom, that’s what I want.” “No, you’re going to have nightmares. Here, buy this nice issue of Space Mouse.”

[chuckle]

And after that I wasn’t on board with the first Dear Marvels, but definitely by the second year, I was buying everything I could get my hands on. I couldn’t get over how much I liked his work inked by Chic Stone because it looked ‘cartoonier’. It looked more like the Fantastic Four Cartoon Show that Hanna-Barbera did.

[00:40:08]

But he was a big deal to me, especially when that first issue of Not Brand Echh came out. Because I never realized that cartoonists could draw both adventure and funny stuff, equally well. And Jack’s sense of humor just killed me. I didn’t realize that he’d more or less written scripts on those too. Stan added some stuff, but a lot of that was Jack’s humor. Jack had a really unique, super funny and unique sense of humor to him.

Shaw!: So, when I met him, I told him. I said, “Jack, you’re always my favorite cartoonist, but now, it’s just unbelievable.” And I remember, he really had a big grin on his face when I called him a cartoonist because everybody else was kind of kissing butt and saying, “You’re the greatest thing since Leonardo da Vinci”, or whatever. But Jack liked to refer to himself as a cartoonist, not because of the style but… You go far enough; the real cartoonists are guys that wrote and drew their own stuff.

Alex: Yeah. Milton Caniff and those guys.

Shaw!: Yeah. So, that’s how Jack thought of himself, because those guys were his heroes too. But we kind of got each other, strangely enough. And I had the balls to ask him if he could send me a drawing. And about two weeks later, he did. And he didn’t know anything about me really, other than I was a hippie who liked his work. He sent me a drawing of me in San Diego, being strangled by King Kong. And King Kong is my favorite movie, and he’s my favorite actor.

But I’ll never forget, the one thing that Jack told me… And it’s funny because my career is kind of dependent on me being able to imitate everybody else’s styles… But he said, “Do it your way.” He said, “Don’t try to imitate me, don’t try to imitate anybody. Try to do it the way you think it should look.” And I tell that to the kids all the time. And I say, “This isn’t from me, this is from Jack Kirby.” [chuckle]

Jim: That’s great… Out of the mainstream comic people, would you say, he’s the one that had the most impact on you as a person?

Advertisement

Shaw!: I’d say, Jack and Neal Adams. And Neal because he was the first cartoonist, I met who wasn’t nice to me.

[chuckle]

He was intentionally not nice to me.

Jim: So, I assume, you hadn’t met Gil Kane before that then?

Shaw!: No, but Gil would come and hang out at my desk at Marvel Productions when he dropped stuff off. First of all, I’m looking up at him so I’m looking into Gil Kane’s nostrils, which was kind of…

Jim: Ironic.

Shaw!: Yes, but also, curious because we talked before at shows and he knew I liked his stuff and we got along fine. But he’s sitting there, doing his “My boy thing”, and I’m like struggling to get something done, and I’m thinking, “I’d never thought I’d think this but, I wish Gil Kane would leave me alone…”

[chuckles]

Where were we before that?

Jim: You were talking about Neal Adams.

Shaw!: It was at the convention… Let me see, third year, I believe. By that time, I was kind of not a star cartoonist, but within San Diego fandom, John Pound and I were the two guys who were kind of we’re everybody had their eye on as possibly being candidates to be professionals.

So, I had my portfolio, and Neal is there. We’re not in the viewers’ room, we were in a room… I remember the carpet, so I bent down and just spread my portfolio open on the floor because it was really big. And there was a whole group of people gathered around us. Not the best way to be showing somebody your work, but it just happened that way.

So, I’m flipping it, I said, “This okay?” “Yeah, yeah.” He’s looking down at it, and the only thing I knew that Neal had ever drawn as humors were those Bob Hope and Jerry Lewis comics. I just wanted his advice. I mean, every cartoonist has advice, right? And I show him everything and I get back up and I say, “So, Mr. Adams, what do you think? You think I have a chance?” And he says, “Well,” and he kind of pretends to ponder, and he looks at me right in the eye and says, “The best thing I can advise is that you give it up.”

And you know that shot in Ghostbusters that they did with Sigourney Weaver sitting on a chair and it was on a track so it looked like everything’s pulling away from her? That’s exactly how I felt.

Alex: What was this, 1974 or something? ‘75?

Shaw!: ’73. I think.

Alex: ’73.

Shaw!: And so, anyway… Neal gets this look in his face like, “Holy crap! This kid is having a heart attack.” And he suddenly goes, “Well, I mean, maybe you could talk to Joe Orlando. Maybe you could talk to Sol Harrison.” And I was like, “I don’t want to talk to anybody else right now. [chuckling] It’s like you got in my head.” Because all the cartoonists I’ve met by that time were nice guys. I didn’t realize I’d meet Neal as a nice guy.

So, anyway, I don’t even remember exactly how it ended. I think I thanked him. I mean, I was just like, “What was that?”

[00:45:05]

But about… I don’t know, it was probably in late 1980s, Neal took me and my wife, and Frank Miller and Lynn Varley out to dinner. And after we all ordered, he stands up, and he goes, “Well, see, it worked.” Apparently, Neal said that to anybody he thought had potential.

Jim: Wow… I wondered about that. If he were going to say that.

Shaw!: But he seems to think that that… Now, this is funny because I love Neal, but Neal, like every cartoonist has a very healthy ego. We have to. “Here’s some lines on a paper, would you please give me some money?” You know what I mean? Takes a bit of nerve to even ask that. But Neal has worked in advertising, much longer than I have, and he really knows how to sell something.

But he really thought that somehow, that him, telling us that was what gave us the drive, and the stamina, and the backbone to face it and do it. Now, nothing would have diverted me from my goal to do it, other than a lot of rejections from people that were hiring me. But the funny thing about Neal is he can really do good cartoons. In fact, the earliest stuff he did, I think was for Archie, and Atomic Mouse.

Alex: I think his first panel was the transformative fly that he did, and it was like redoing a Kirby panel and they liked his panel better or something.

Shaw!: It was some of those one page-joke things for Archie.

Jim: Oh, right. Right. I remember those… So, Scott, I’m going to turn you over to Alex as soon as we do the Hanna-Barbera stuff, and then I’ll come back to comics, after he talks about animation.

Let’s talk about working for Marvel, when they got the license to Yogi Bear and the Flintstones, and Laff-A-Lympics. I was buying all of those at the time that you were drawing those, because I bought everything Marvel did at that time. How did you get that job and what were you doing with it?

Shaw!: Well, that was because Mark Evanier, suggested me to Chase Craig. I was still doing underground comics pretty much, and I was working at the comic book store down the street from Hanna-Barbera.

Jim: Which store was that, by the way?

Shaw!: It was called The American Book Company, and they did mail orders so, I did all the art cartoons for the catalogs and stuff. As I’ve said, the main reason I took that gig was because it was near Hanna-Barbera, and I knew I’d wind up being picked, and indeed, it happened.

But Mark was actually the guy that put my name and phone number on the editor’s desk. My first job was to ink something with tissues, over a light board which I’d never done before; and is really, burns out your eyeballs, trying to ink looking down with the light coming out through it. But that was kind of nerve-wracking.

After that, I started inking a lot of stuff, and then that editor decided to retire and Mark took over. So, he started giving me penciling and writing stuff too. We were also doing a ton of stuff for overseas, which is even better because then if I screw it up, at least nobody here had to see it so I wasn’t as embarrassed.

Shaw!: But we weren’t really working for Marvel. Marvel was buying these things but it kind of was almost like Western Publishing packaging for Dell. Mark would write out the whole thing, pretty much put it together. They wanted to edit it. I don’t know if you even remember, but somewhere I’ve got it, there’s an ad for the Hanna-Barbera Comics that I think Marie Severin drew without any model sheets. And It shows why they had to get us.

The reason, by the way that Hanna-Barbera and Marvel were involved, was the previous license holder, was Charlton Comics. They just paid. These are just simple little cartoon characters anybody could draw them. And frankly, 90% of them are just horrible. And the people overseas that were reprinting them, noticed they were horrible too, and started complaining to Hanna-Barbera. They said, “We’re not going to print them unless you get somebody that draws these”, because overseas, they appreciate good humor art a lot more than American comics.

I never understood why, I think it might have something to do with comic fans being criticized that they’re just like that baby stuff, for reading comics. But why is Garfield like incredibly, not the greatest thing, but I worked on it with Mark Evanier writing, makes it easy to do. But Garfield is so successful outside of comics. But if you have gotten Jim Davis show up at Comic-Con, he’d probably be sitting there waiting for people to notice him.

It’s strange. Now, it’s kind of evening out because fandom and public acknowledgement of the stuff is kind of infusing each other. But for a long time, I couldn’t figure out why comedy and humor stuff was not embraced by comic fans.

In fact, the first adult that I found out that liked humor comics like me was Maggie and Don Thompson. They used to send out a one-paged fanzine called Beautiful Balloons. And some friends of mine subscribed to it was like, “Holy crap! Here’s an adult older than me that likes Uncle Scrooge every bit as much as I do.”

[00:50:08]

Alex: Okay, so when the Marvel/Hanna-Barbera Comics were being done, was Jim Shooter editor in chief then? Because that’s ’78. Was it more like Archie Goodwin?

Shaw!: I never had any contact.

Alex: No real contact, okay.

Shaw!: Quite honestly, he didn’t answer. They wanted to do the letters page, they wanted to do all that stuff, and Mark just said, “No.” and apparently, they had a very specific contract, because all of the books ended at the same time. I don’t know what they were selling but based on the number of them that are out there that are just… Beat to hell. I imagine they sold pretty well. But Marvel was doing that at that time too, to grab up stuff that nobody else had the license on. They did Dennis the Menace for a while.

Jim: I have a question about, in relation to this, had you followed, and were you a fan of some of the comic strip artists that were doing things like that. I think of people like Harvey Eisenberg; who I think was very good.

Shaw!: I think Harvey Eisenberg is one of the finest guys that has ever drawn comics. I just wish he could have written his own stuff. I would have loved to have seen what that was like. I’m good friends with the son, who is also an outstanding cartoonist, Jerry. And Jerry designed a lot of the early Hanna-Barbera characters.

Harvey Eisenberg, I think the earliest stuff of his I can find is from Timely stuff. But he just, even the Hanna-Barbera stuff, these flat designs that really didn’t move around much, he gave them life and dimension. In fact, the Hanna-Barbera movie, Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear, in their model sheets for the movie, they actually just asked… Because he was working for the studio too. He actually just loaned them some of his tissues. They’d cut them up and made just his rough drawings of Yogi Bear into the model sheets.

I think, he, Gene Hazelton, and Ed Benedict, I think they’re the three best ones during those times.

I got to tell you something. Now, that MeTV! is showing them chronologically, I can only even handle watching the first two and a half seasons, after a certain point, they were horrible. And yet, even at the time, I didn’t really notice it as a kid. But really, once you had produced and direct cartoons, you notice.

Jim: So, were people aware? Like when you were drawing Yogi Bear, did people say, “Oh”, they knew who Eisenberg was? Did they understood that the people you were… Like at Marvel, or anybody that you were talking to? Was he a known person?

Shaw!: Mark Evanier was the only person who knew who Harvey Eisenberg was, or Pete Alvarado, or any of the guy that were drawing those comics. I mean, I collected the good Hanna-Barbera Comics, really until maybe 1970.

Jim: And the Flintstones too. I mean, there were good stuff coming out of the comic strip stuff, more than the comics up to a certain point.

Shaw!: He was writing and drawing it for a long time, but a lot of times, he would hire Harvey to do the final pencils. I don’t know if he was inking them or not. He had a couple of inkers that he liked or they had or liked them there on Western. In the comic book, Pete Alvarado was also doing them. A fellow named Phil DeLara was doing a lot them, who had worked for Warner Bros. Almost all the guys at Western had worked on these characters in one way or another for the studios, except for Eisenberg who walked away from animation, pretty much, except as an adviser, on occasion.

Jim: Were you thinking that this was going to be a stepping stone into a Marvel career where you were going to be drawing Spider-Man or something? I’m being facetious but did you see it was a way to get in to the big two through this? Or was this, you realized what this was, was a continuation of your cartoonish funny animal kinds of things, only just on a more commercial level.

Shaw!: Well, it’s interesting because I didn’t really expect Marvel to hire me. But about the same time as I was doing those comics, I was still working and managing the comic shop. In fact, it used to be a dentist office so it had a bunch of little rooms, in the back. And the back one was my studio. It’s really my place… At least the first place, I’m sure there’d been many since, where the comic went from being a blank piece of paper to a back issue.

But I mentioned earlier that that’s where I got to know Roy Thomas. And Roy and I met at, when he came out to Comic-Con, I think in ’75. But he admitted he didn’t remember me. Every kid wanted to meet Roy Thomas then. He was the best writer. He and Denny O’Neil were the two top guys at the time. In time, we had Kirby, Steranko, O’Neil, and Adams there at the same time, and they were all the most guys everybody was looking at in that wing.

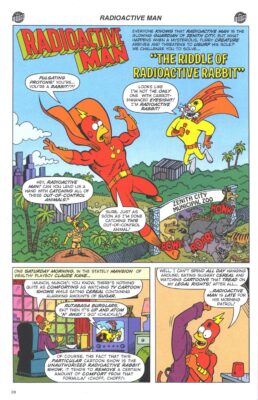

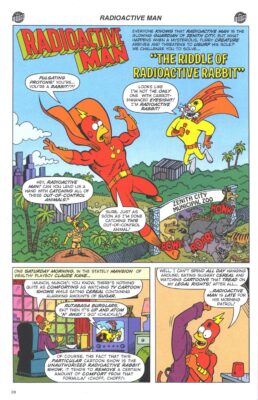

Roy came in a couple of times, and we hit it off and he asked me if I wanted to do a back-up in What If. And I pitched him, what if a radioactive spider was bitten by a radioactive human? And he liked it, and I did it up… I had a panel with Peter Parker and I got my neighbor Dave Stevens to draw.

[00:55:01]

When I moved to LA from San Diego, I brought Dave up with me, kind of… He was probably three or four years younger than me. We had an apartment. My apartment building, so I kind of look after him a little bit. He could help me out. We had four cartoonists by the end of… My wife throwing me out, we had four different cartoonists living in that building.

The Man-Spider thing has been reprinted I think three times by Marvel because they’d never done anything with it. I think it has something to do with the fact that I wrote it and drew it. And because I did it during the period where you had to sign the back of your check.

Jim: This is the last question, and then I’ll take it back up with Captain Carrot when I come back. But when you were associated with Destroyer Duck, were you at all concerned, you were burning a bridge, or that Marvel was going to be mad at you for any association? I know you were friends with both Gerber and Kirby, so it was a natural thing for you to contribute to.

Shaw!: Well, I was an underground cartoonist. I didn’t care whether Marvel liked me or not. I kind of assumed if they want to hire me, it’s going to be on my ability but it never was a problem. I mean, I want to support Steve and if Jack Kirby was in on it, it was fine with me.

Jim: And can you talk about that? Because not everybody has had access to and has read that. What was the story that you did for the first issue of Destroyer Duck?

Shaw!: I just inked it, really. It was something that Marty Pasco had written. And I was really excited though to ink Joe Staton because I think I bought the first issue of Primus because it was like, “Whoa, this guy is…This guy draws differently. He kind of draws the way I draw, if I drew…”

Jim: We did an interview with him. It was one of my favorites. I’m a huge fan of his work, going all the way back to the beginning as well.

Shaw!: We have something in common in that… Well, a couple of things. One is that we both got to grow up to draw our favorite characters. But also, after Roy and I had developed Captain Carrot to a certain degree, and had pitched it to DC, and they seemed to want to do it, because they kind of asked Roy to come up with something that they might be able to use as a cartoon show.

Without telling me, they went to some other people, including Joe, and asked them if they’d like to draw it. So, I assumed they were kind of planning to rip me off. By the way, I’m not mad at Marvel about anything, DC is a whole another story.

[chuckle]

Jim: Well get to that.

Shaw!: Since I don’t expect to get a call from them soon, I’m happy to talk about that. And then Joe Orlando came back to me and he had all these drawings of the characters drawn in a DC Comics, pseudo-Jack Kirby style, as opposed to the way I draw them, which looked like cartoon characters. Then I suddenly had to learn how to be their cartoon, George Perez and that’s kind of why I had ultimately lost the gig. Because I just couldn’t draw fast enough to add all that useless hay on everything.

I mean, they wanted it to look like a certain way and I really did my best to deliver. And besides, they kept saying, “If you meet your deadlines, we’ll pay you more.” I said, “No, I have to take other jobs to meet my rent deadlines.” So that was another problem, I wasn’t young enough to have three roommates like most young comic book artists.

Alex: Yeah. That story by Marty Pasco, that Staton penciled and you inked, that’s the satire of Alex Toth throwing Julie Schwartz out the window, right?

Shaw!: Or Bob Canniger, or whoever you might want to think it is.

Alex: Yeah. Because the original story suggest the check issue between Toth and Schwartz but then, Staton drew Canniger out the window, in that story.

Shaw!: Yeah, well I heard the story told so many ways, I think he just decided, let’s make it an amalgam of the two best known.

Alex: Of the two people that were kind of there… Yeah. Did Staton draw the French hat on Toth or did you add that?

Shaw!: No, he was wearing a beret when I penciled, I didn’t edit. But what’s funny is, it’s always the guy that’s going to get thrown out the window, that changes, but it’s always Toth.

Alex: [chuckle] Yeah, it’s always Toth doing it. Did you know Toth too? Because he was out in the West Coast also.

Shaw!: Yeah, he was in Hanna-Barbera when I was there.

Alex: Yeah.

Shaw!: He was, I think, bi-polar. He’d go by, I’d go hang out in his office with him. Once in a while, we’d be talking and stuff. He was very friendly. Next day, he walked by me and kind of, “Scott Shaw!… Hmpf…” and stick his nose up in the air. Like he decided I was a communist, overnight or something. Every birdie I know, said he’s like that, he likes you and then he decides he doesn’t like you.

Alex: Yeah, I’ve read and heard that.

Shaw!: Yeah, because he was one of those guys that fans didn’t really notice but other cartoonists respected Alex, tremendously.

Jim: Sure. Rightfully so.

Shaw!: He could do a little bit of everything. He was so hard on himself though. You know why everybody has the page that Alex gave them is always out of the Lost World adaptation, because he hated it. So, he’d just give those away to anybody he knew.

Oh, by the way, one day, Mark Evanier and I, we’re going to go up to see Alex. Mark had set it up at his house, and it’s up by the Hollywood Hills. So, we get up there, Mark raps on the door. Nobody answers. Nobody answers.

[01:00:04]

We weren’t bearing groceries, I don’t think. I mean, he used to invite people in if they brought him groceries. But Alex just would have these moods where he didn’t want to talk to anybody. I don’t know what Mark had, but he brought something for Alex.

We go back out to Mark’s car. He opens up the trunk of his car. He put something in, the trunk’s still open, and this car pulls up, that has a realtor sign on the side. “Do you boys know where to find so and so?” And Mark says, “No, we don’t live in this neighborhood so we don’t know.” And I said, “Yeah, anyway, we’re just doing a drug deal.”

And the car peals out of there. I’ve never seen Mark without a comment. He didn’t look mad, he didn’t look… He just looked like, “What’s going on here?” [chuckle]… So at least Alex gave me a funny story.

Alex: As you’re doing the Hanna-Barbera Comics, you were then hired as layout and character designer for the 1979 New Fred and Barney Show. Is that right? How’d that come about?

Shaw!: I got a call, one day, and I don’t remember who it was from. But they asked me if I was interested in coming and working in Hanna-Barbera, and I really didn’t know what to say, because I was working freelancer and I was young. And it was like, “Wow, I get to hang out. I can draw on my underwear; I can sleep in late. I don’t know if I want to punch a clock again.” I said, “Well, I don’t know.” Then they said, “We’re going to be doing a new Flintstone show.” I say, “When do I start?”

Alex: Yeah, because you like the Flintstones. Yeah.

Shaw!: And people think I just innately like anything Flintstones. As I’ve gotten older, it’s really, I just like about the first two and a half years of the show. I like the best toys. But it’s not like Hanna-Barbera every strove for perfection, so an awful lot of that stuff… It’s like you don’t know how many people on Facebook send me pictures of people with shitty Flintstones cars. Please, no more of those.

Alex: [chuckle] You hear that, ladies and gentlemen? No more.

Shaw!: I know what the real one looks like. You don’t have need to show me anybody trying to make it look like that… But the Hanna-Barbera thing, they brought me in almost immediately, but it wasn’t to work on the Flintstones. They hadn’t gotten the go ahead yet, so they didn’t even have any scripts yet. But they know it was the same. And they had seen my stuff on comics books, and they liked my comics, which is interesting because the year…

Advertisement

I don’t know how many years, maybe three or four years, but for when I came up to make my first big trip to LA to show off my portfolio, I met Hanna-Barbera who was an ex-Marine, and apparently, everybody said he was the meanest sonofabitch of the place. And he was an ex-Marine, and I was a hippie. And yet, I think, because I was so used to being a Navy kid, I was so used to calling him sir.

Alex: Yeah, yeah, because of your dad who was in the military.

Shaw!: Yeah. I messed with him. He’s like, “Why is this hippie respecting me?”

But in any event, he was very kind and he said, “Look, I just don’t think that you’re ready. You’re showing me stuff that’s underground comic type stuff, we need to see drawings of you drawing our characters.” And I was like, “Oh, I never even thought about that. Can’t you tell that I can draw them?” “No.” That poor man, by the way, died on the toilet at Hanna-Barbera.

Alex: He lived and breathed his work, it sounds like. And digested his work as well.

Shaw!: He was granted out some more work at Hanna-Barbera… Anyway, the job turned out to be in layout, but they also were having me do a lot of the character and prop design. They’re trying to find out what my strengths were, and they were trying to train me at the same time. That happened the entire time I worked for Hanna-Barbera.

I left for a while to do Captain Carrot and I came back after that, and after working at Marvel. I saw people get fired or laid off all the time, it was just part of animation. Everybody has to spend the summer doing something else because we don’t get the pick-ups until late summer, start getting the shows ready. And I never realized until many, many years later that Bill and Joe showed a great loyalty to me because they were trying to train me. I mean, I went from being a layout guy to be a producer.

Alex: Right, they saw the potential. Right. They wanted you to use your talents.

Shaw!: Floyd Norman got laid off and I was kept on, and he was my roommate. I’m thinking, “What is going on here?” Because Floyd had done all kinds of things. He knew how to make cartoons. He had his own studio at one time. I’m just a kid, why are you keeping me? But they had me working in publicity. They had me working in presentation. I eventually became a writer. And I thought they’re just making sure I can do every job in the place, but animate. Because by that time, I would have had to be an Asian to be animating because they were sending them all over to Asia.

But that was kind of my version of college. I was having too much fun in college to learn anything. But at Hanna-Barbera, it was like, I was so happy to be there.

[01:05:00]

A lot of the old timers… I mean, I worked with guys, not only work with them but they had to kind of show me their work. And I think that was one reason I was given that job, to be a layout supervisor. It was that way; I’d be exposed to guys that knew what they were doing. And some of these guys have worked on Snow White and Pinocchio.

Alex: Yeah, the seven old men, or something?

Shaw!: Oh, no. None of them were there. But the guys that have long histories with every… I mean, at one time, there weren’t people trying to get in to animation, it was kind of a finite society so if a guy quit at one studio… It was like musical chairs. Okay, somebody would go over there… It’s just like, “Oh, I’m going to see my different group of buddies at the other studio.”

Now, kids are being told that it’s like being a rock star, and I’m usually actually trying not to tell kids, “Oh, you’re going to get the job.” I say, “Do this for fun. And if you get a job, that’s a bonus.” Because that’s a much more realistic thing now.

But these guys thought it was hilarious that I was so impressed to be working with them. Because I knew all their names from the old Hanna-Barbera credits. They were kind of laughing behind my back but not in a put down way. They felt like, “Who is this kid? He actually thinks that this place makes good cartoons. “

[chuckle]

At that time, I knew they weren’t making good cartoons, but those guys taught me how to draw. That’s when my works started getting better. And it wasn’t good yet, but it was getting a lot better because I was looking at, and working with people who had forgotten more than I’ll ever know.

Owen Fitzgerald, he did a lot of comic books, and really good comic books. Jack Manning was there. Pete Alvarado was there. I was working with all them. Also, there were guys like Tony Rivera who had been a layout guy at Hanna-Barbera since the very beginning. He one time came in, Floyd sitting there, and we’re checking layouts and writing stuff down then Tony comes in and he pretends to be confused. He was an old guy. But he wasn’t confused, he knew what he was doing. He said, “Scott,”… He made his voice sound kind of like he was more helpless. I was like, “That’s bullshit, Tony.” But he comes in and says, “I need some help on this layout.”

And it was a pan, and I forget exactly what the element was but it was what we called a bicycle thing. So, one thing was holding still while we’re panning by, and the other things are passing through. And so, you had to do it on certain pegs because the camera guys needed to be able to shift the stuff around so it wasn’t a problem for them after we peg everything.

Anyway, so he does it three different ways, and spreads them out and shows them to me and I’m like, “Why is he asking me?” And then it clicks on, “No, he’s teaching you, you idiot. Pay attention.” Anyway, he’s done and say, “What do you think?” I said, “Well, Tony, I think the way you’re showing it, this is the only way that it makes any sense, right?” And he looks up at Floyd and he goes, “Ah, this kid’s good.” And just walked out of the room. It’s like, he didn’t get paid for that. Nobody said, “Hey, Tony, would you show Scott how to do this?”

Now, it’s kind of like the Thunderdome, everybody’s trying to get everybody else’s job, and everybody’s looking over their shoulder. And two, studios are no longer like a cartoon studio, where you can pin stuff up on the walls and play practical jokes on each other. I mean, we weren’t like Termite Terrace but we got pretty rowdy at times. Bill and Joe understood one thing, “Leave us alone.” If we’re hitting their marks, and we’re not asking for more money, “Leave them alone.” But we were all overaged children. We had a contest once, to see who could cause the biggest crash, that they’d hear it downstairs in the ink and printing department.

[chuckle]

That was our goal during the day, not getting the work done, that we just did. Floyd once told me this, coming from the guy with his experience means a lot. He said that of all the studios he worked in; he didn’t look forward to going in any studio like he looked forward to coming in HB. That was my break into the business.

Alex: Yeah. That’s where all the connection start… So, then in the ‘80s, Harvey Comics basically fallen apart, but the Richie Rich cartoon went from 1980 to 1984, and you had some involvement in that as well, is that correct?

Shaw!: Yeah, I helped develop it. I think they knew, because I’d worked in comics and I might see some things. I wasn’t responsible for the show, at least the backgrounds looked more like the comic. But it wasn’t my idea to trace Dollar the dog’s features over a model of Pluto for example, who did it, I’m not saying. They did have a problem with Richie Rich’s age. And the main reason for that wasn’t his age in particular, they didn’t like the idea that his head was like three times bigger than his father’s.

[01:10:02]

Shaw!: In the comic, they always kind of had him on the foreground and the dad on the background or the dad on the foreground and the kid way in the background. So, you aren’t really noticing them standing together, but in Saturday Morning, there’s a lot of characters just kind of standing in the same lines, looking at each other.

In the development, I had to draw Richie, at six-month intervals between the ages of six and 16, which was really hard. How do you age somebody that barely has any features? With that Dagwood haircut… maybe do something with it…

[chuckle]

But it sold, and then they came to me and had me develop a Baby Huey too. I had mixed feelings about that because I never liked Richie Rich as a kid either. I was a big Uncle Scrooge fan so it wasn’t the money thing, it was just… Harvey Comics, even as a kid, struck me as the comics that your grandmother would give you. They were just too babyish for me, even when I was practically a baby. It was like they’re well drawn, they’re well written, but they’re just too safe.

Well I do have one that shows that those guys were reading other comics. I’ve got one where, I think it’s Casper or Spooky, but the monster is a big swamp monster named Voodoodoo???

[chuckles]

People comment on me drawing the turd, “Hey, here’s a Harvey Comic that’s not…

Alex: Voodoodoo. Yeah. It’s clever. I like that.

Shaw!: [chuckle] But don’t tell Bob Overstreet, he’ll mark it up.

Alex: [chuckle] So, now, also another cartoon I really loved as a kid, and actually, the New Fred and Barney, Richie Rich, then this next one Muppet Babies, I mean, I watched all that stuff as a kid. Formative, for me because I really didn’t read the Harvey Comics but I watched the cartoons. But let’s talk a little bit about the Muppet Babies. Now, that one, from 1984 to 1991. I loved that there was like old black and white clips of old movies mixed in to it. Like that was actually, I think, where I actually figured out that there was the universal monsters, because it would have stuff like that. Tell us about your involvement in the Muppet Babies cartoons.

Shaw!: I was always a fan of the Muppets, but I really became a fan of the Muppets, once I was working on that show. We never worked directly with Jim Henson. Michael Frith was the main guy that we worked with, who was one of the guys that’ve been with Henson’s company for years. He was an outstanding illustrator himself. Lots of kids’ books and lots of the Sesame Street books, and things like… He kind of did the ones that Jack Davis didn’t do there when they first were new.

Shaw!: Anyway, we would get very thoughtful notes. We were dealing with people who’d never worked for Saturday Morning, who’d never worked for the cheaper, tawdrier aspects of kids’ entertainment. By the way, when Sesame Street came out, I was in college, and I’d lay in bed all day, on Saturday, they’d show all of it for the week. I was convinced that this is going to change animation forever. Every show’s going to be in a completely different style. No, that didn’t happen. And I wound up in Hanna-Barbera, so there.

Anyway, the Muppet thing, first of all, we had a producer who understood… He never said this, he wasn’t the kind of guy that make little speeches, but he essentially made it clear that a good idea is a good idea, doesn’t matter where it came from. There was a season, for example, where he told everybody… I think it was the second season, we had an hour’s worth, to do for each week. A half hour showed an hour when we got our first in and the ratings were good too.

He was buying spring boards. He was paying I think $100 for spring boards, he wouldn’t pay out of his pocket but some of the assistant gophers were getting them. They became writers, one of the editors did them, and I became a writer for them too. And I’ve been writing anyway, but it was the first time somebody said, “Hey, we’d like you to write, this.”

What it was, was, this was a good example to have everything. I mean, I switched around, because I was also the overseer of the model sheets… By the way, Chris Sanders, the guy who created Lilo and Stitch, I was his first boss. He’s still speaking to me so I guess I was okay.

Alex: Sounds like it was a positive experience.

Shaw!: Yeah, but this was fairly far in on Muppet Babies. And this was the same time that Marvel had taken on a ton of work relating to toys, and they also made a deal with King Features, to do this… In my opinion, terrible show that was kind of a rip-off, in a way, of Masters of the Universe, called Defenders of the Earth. I think. And it was kind of like all their classic quasi-superheroes: Mandrake the Magician, and I forget who…

Alex: Flash Gordon was in it too.

Shaw!: If they were smart, they would have added Popeye, they were all fighting Ming the Merciless, they all had teenage sidekicks, it was just horrible. Everybody at the studio assumed that, “Oh, we have the rights to Flash Gordon.” Now, they didn’t seem to understand how these contracts work.

[01:15:00]

“No, it’s for this particular project, you have the rights to Flash Gordon.” So, they wrote, and they went through a script that was all Muppet Babies stuff, based on one specific Flash Gordon serial. And so, we get the whole thing boarded and the producer gets a call, and he calls me, and he says, “Guess what, we can’t use that movie because we never signed for it.” Though he said, “But we have something you might like even better.”