Comic Book Historians

Gary Groth Interview: Publisher, Comics Critic, Historian part 2 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Fantagraphics publisher, The Comics Journal co-founder, and Genius in Literature Award recipient Gary Groth, in part 2 of a 2 parter covering his full publishing career starting at age 13, his greatest accomplishments and failures, feuds and friends, journalistic influences and ideals, lawsuits and controversies. Learn which category best describes ventures like Fantastic Fanzine, Metro Con ‘71, The Rock n Roll Expo ’75, Amazing Heroes, Honk!, Eros Comics, Peanuts, Dennis the Menace, Love and Rockets, Jacques Tardi, Neat Stuff and the famous Jack Kirby interview; and personalities like Jim Steranko, Pauline Kael,Harlan Ellison, Hunter S. Thompson, Kim Thompson, CC Beck, Jim Shooter, Alan Light and Jules Feiffer. Plus, Groth expresses his opinions ... on everything! Edited & Produced by Alex Grand.

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, Photo ©Chris Anthony Diaz CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Music - standard license, Lost European.

CBH Interview Series

Comic Book Historians Podcast

#TheComicsJournal #GaryGroth #Fantagraphics

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Fantagraphics publisher, The Comics Journal co-founder, and Genius in Literature Award recipient Gary Groth, in part 2 of a 2 parter covering his full publishing career starting at age 13, his greatest accomplishments and failures, feuds and friends, journalistic influences and ideals, lawsuits and controversies. Learn which category best describes ventures like Fantastic Fanzine, Metro Con ‘71, The Rock n Roll Expo ’75, Amazing Heroes, Honk!, Eros Comics, Peanuts, Dennis the Menace, Love and Rockets, Jacques Tardi, Neat Stuff and the famous Jack Kirby interview; and personalities like Jim Steranko, Pauline Kael,Harlan Ellison, Hunter S. Thompson, Kim Thompson, CC Beck, Jim Shooter, Alan Light and Jules Feiffer. Plus, Groth expresses his opinions ... on everything! Edited & Produced by Alex Grand.

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, Photo ©Chris Anthony Diaz CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Music - standard license, Lost European.

CBH Interview Series

Comic Book Historians Podcast

#TheComicsJournal #GaryGroth #Fantagraphics

[01:25:00]

Groth: Well, our interviews, yeah… I think there was a point where we started… Maybe it took a few years, but I always wanted to publish good interviews.

Alex: And just some names, just so the audience… I don’t know if they know, but Bill Gaines, Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Robert Crumb, Howard Chaykin, I mean, a slew of people; amazing, unique people. And you guys really got them to thought provoking discussions with them.

Groth: Yeah, and we interviewed a spectrum of artists. Like people in the previous generation… This is a detour but I am somewhat disheartened by what I perceive to be the ahistorical vent of the younger generation. So many younger cartoonists just don’t seem to care about what’s preceded them.

Alex: And where it all came from.

Groth: Unless they can criticize the political or cultural content of it, which is easy to do. But I remember, when I was a kid, I was interviewing guys who were 20s older, 30 years older than me and I was… And as I got older, and I got in to my 20s, I became much more curious about people like Harvey Kurtzman.

Alex: You guys had C. C. Beck saying quite a few interesting things.

Groth: Yeah, yeah. I interviewed C. C. Beck in his place in Florida. And he was a much older guy that me at that time. He was in his… Well, he was probably about my age now, but I was probably about in my late 20s, and I was intensely curious about his career and his life, and what doing comics was like when he was doing them in the ‘40s and 50’s.

Alex: Yeah, it’s interesting because even though you’re obviously of a left-wing political mindset, you still were printing interesting things from creators like… Because C. C. Beck was writing more right-wing stuff sometimes. Right?

Groth: Well, he was more curmudgeonly than right-wing. I think. I don’t think he had any coherent ideology.

Alex: [chuckle] I understand. Okay.

Groth: Though a little more conservative but he was a cranky guy and I appreciated that.

Alex: And then Rick Marschall, whom we’ve had on the show before.

Groth: Rick does have a coherent right-wing ideology. Yeah.

Alex: But he’s also an amazing historian. Right?

Groth: He’s a great historian, yeah. He knows more about comics than most people are going to ever, ever know.

Jim: I was nervous about that interview. I thought it was going… Because his politics are not mine. And it’s one of my favorite interviews that we did on this. He’s just a delight to talk to for hours and hours.

Groth: Yeah, yeah.

Alex: I kind of had to twist Jim’s arm to do it… A little bit. But he got in to it actually, a lot.

Groth: Well, Rick and I keep our politics, mostly, separate. And we bonded, frankly, over our love of comics and our love of the same artists. I mean, Rick is really peculiar because he’s one of the few members of the right-wing who’s actually cultivated.

Alex: Right.

[chuckle]

He knows a lot.

Groth: Yeah.

Jim: [chuckle] That was my impression. I just didn’t say it out loud.

Groth: I’ll say all these things out loud.

[chuckle]

But he’s got wonderful taste, he’s got exquisite taste, and he’s a great historian. We transcended out political differences.

Alex: Right. And you’ve published quite a few things with his name on it. Obviously, it’s a clue that there’s a mutual respect. And I think, the younger generation needs to learn from these kinds of interactions.

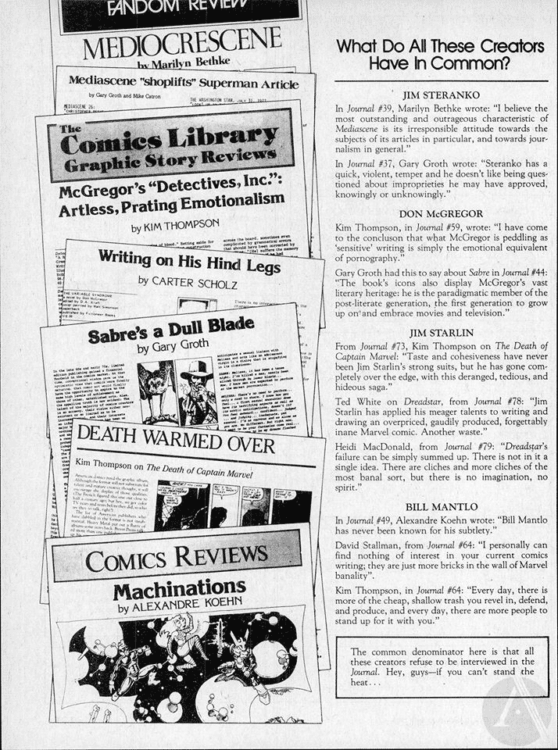

But I’m going to throw out some sentences that are a little, I don’t want to say controversial, but you probably know some of these, I’m sure. But there were times when The Comics Journal would really bust someone’s chops, pretty good. So, obviously, you wrote in issue #37, “Steranko has a quick, violent temper. He doesn’t like being questioned about improprieties he may have approved knowingly or unknowingly, about Don McGregor in the Journal #44. This book’s icon also displays McGregor’s vast literary heritage. He is the paradigmatic member of the post literate generation; the first generation to grow up on abrasive movie and television, which isn’t bad.”

You said about… Okay, not, you didn’t but someone else did about Jim Starlin. “Starlin has applied his meager talents to writing and drawing an overpriced gaudily produced, forgettably inane Marvel comic.” That one’s harsh, a little bit. But I think of Bill Mantlo, someone wrote, “Everyday, there is more of the cheap, shallow trash you revel in, defend and produced. And every day, there are more people to stand up for it with you.” I personally… And then someone else wrote, “I can find nothing of interest of your current comics writing. They are just more bricks on the wall of Marvel banality.”

Groth: You want me to comment on that?

Alex: [laughs] Well, I’m just saying, it’s an interesting trend in that… Yeah, like you guys would zero in on this stuff.

Groth: I think that was all absolutely essential to put it out there. I think these comics had gone far too long without being criticized…

[01:30:01]

And finally, the time had come, to apply mature critical standards to what were essentially relentlessly idiotic and adolescent crap, that comics traded in for its entire existence, with very few exceptions.

Comics is such a peculiar medium and industry. Comic books, I’m talking about, specifically. But the history of comics books is just a history of such just crap. And my feeling then, was that it doesn’t have to be that way. I mean, there can be work of genuine aesthetic value.

Alex: What do you think of this sentence? “McGregor is peddling as sensitive writing is just the emotional equivalent of pornography.” Looking back do you feel like these are true statements?

Groth: I think they’re defensible and arguable critical statements, yeah.

Jim: Did Kim Thompson, moderate you a little bit in terms of that? I mean, when he was there… Because I’ve heard him in interviews, explain things that you’d say. He would say, “I understand why people were offended by Gary’s piece, but they’re not quite hearing it right… “How helpful or how essential was he to Comics Journal at this point. Partly because of that tempering of your, let’s say, honesty.

Groth: Well, several of the harshest things that you just read were by Kim.

[chuckle]

Alex: Yeah, that one was. The porno McGregor… Hashtag porno McGregor… Now, it would just be just be #pornomcgregor, is how that would be now, with the current generation.

Groth: Right, I recalled that when you read that. It’s Kim who actually wrote that.

Alex: That’s cool.

Groth: Kim’s not a moderating influence at that time… Actually, he was never a moderating influence. He might have tried to be, occasionally but he probably never succeeded. I probably became more militant, and Kim became less, militant over the years. Now, it’s funny because you’re talking about… You just quoted Kim’s review of Don McGregor’s… What was the name of the book? Was it Detective Inc.?

Jim: Yeah, probably.

Alex: Yeah. Probably, because that was Journal #59.

Groth: But now, Kim loved McGregor’s work. Absolutely loved it. I mean, if you go back, to fanzines that Kim contributed to, I guess in the early ‘70s, you’ll see a lot of rave reviews of Don McGregor from Kim. And Kim too, had the scales lifted from his eyes at some point and recognized that McGregor was a terrible writer.

So, I think we were both undergoing an education throughout the early days of The Comics Journal. And we’re very much in sync. I think Kim started moderating his views at some point, and at some point, I think I hardened my views.

Alex: Okay, so you hardened them, as in like you feel more specifically and more intensely about the same kind of thing.

Groth: Yeah, yeah. I felt more strongly than ever. That the comics were capable of a certain level of aesthetic expression, and the artists who were doing lousy work… We’re really confounding the medium by doing that.

Alex: Right. Because, I mean, just because a 12-year-old kid buys it, doesn’t mean it’s good. Right?

Groth: Yeah, but it can be. It can be good comics for 12-year-olds, but yeah, of course. Of course. I mean, comics will always appeal to children, and that’s why they’ve gotten away with so much junk.

Alex: There’s so much good information here that we’re going to have to carry this into a sequel episode. Stay tuned everybody, in two weeks, for part two of the Gary Groth interview.

[01:33:54]

PART 2

Alex: Welcome back for part two of the Gary Groth interview. Let’s continue.

Jim: I’ve an interview I wanted specifically ask you about for a second, which was the Jack Kirby interview that you did. My only concern about that was, the point in time that he was at, it seemed like he said things that have later been used against him to impact his credibility to say, “Well, he didn’t really do all of that.” and you can’t say that, “No one else ever did anything creative.” and so forth. It was a hard interview as you were doing it, as a journalist, do you feel like you’re supposed to protect the subject?

I would say, “No, you shouldn’t”, but at the same time the fan person in me was like, “Oh man. this is going to have ramifications. People are going to quote this on Facebook 50 years from now”, because I was that prescient, and so I worry about that. When you were doing journalism, did you ever think about those aspects? The impact it was going to have.

Groth: Well… I was certainly aware of them, but I’m also from the Oriana Fallaci school of interviewing, where I think that the interview subject has to stand or fall from what he says. I mean, have I cut out stuff from an interview that I think for prudential reasons, I probably have. I can’t think of any anything at the top of my head, but I probably have. But with Kirby, I caught him at a specific time, and he was angry. And of course, I think he had a right to be angry.

Alex: Right.

Groth: I wanted to capture that anger too, because Jack did not express his anger often. He kept it in. He repressed his anger. And at this point, for whatever reason he decided to let go. And yeah, I mean, he said some things that were exaggerations. He said Stanley didn’t write a word, that’s not true.

I understood what he was saying, and I think anyone who understands the history of Kirby and Lee’s relationship, knows what he was saying, which was of course, that he wrote the stories in the sense that he laid them out, and he wrote notes on the sides of the pages explaining what the action. So, he in effect, wrote the stories but it was Stan Lee who wrote all the dialogue for the stories. And I think everyone knows that. So, that was an exaggeration, or a lie depending on how you want to spin it.

Alex: Like when he said he created Spider-Man’s costume, were you kind of thinking, “Okay, no you didn’t” but you let him keep talking? How’d that go?

Groth: I can’t tell you what I was thinking at that moment, I really don’t. Looking back over that interview, I actually wish that I had prepared more thoroughly than I did. I don’t know, you might notice… I did that interview in ’86? Something like that…

Alex: No, it was like ‘91 or so… No, ’90…

Jim: No.

Groth: No, it had to be before ’89… I’m not sure if it’s ’86 or ‘87 maybe?… But I wish I’d prepared a little bit more so I could’ve delved more deeply into some of the things he said. But I’m not unhappy with that. I think it shows a side of Jack that is too often not shown.

Alex: Do you still have that audio tape of it?

Groth: Yeah.

Alex: Wow, that’s cool… Two questions about TCJ real quick… So, Jim Shooter, there was a lot of articles on him in the ‘80s, obviously. Do you feel… There’s this whole thing of cancelling a person these days; cancel culture, or whatever. But it wasn’t really like to that degree back then, maybe it wasn’t there really in any real way, but a lot of the articles I was just kind of looking back on, about Jim Shooter and about work for hire, it seemed maybe… And I could be wrong, and you can correct me if I am, is that it seemed like they were kind of conflating the Kirby original art and lack of creator status, and evil Marvel corporate people, and then conflating it with Shooter and kind of his OCD personality, and kind of combining it in a way where- could it have been that you had potentially stained his reputation with the baby boomer generation that was reading that, to the point where now, he wasn’t as viable? And now, he’s in a poor house now because he’s not as viable?

Groth: You mean about now?

Alex: No, I mean like… He’s still alive, right?

Groth: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Alex: I mean, so the stuff that happened back then, did it mess up the fan base, where now, like no one was interested in him anymore? Or did he genuinely was his own worst enemy in that sense?

Groth: Well has he been cancelled.

Alex: I don’t think… No. I’m saying is like when people read enough bad things about a person and they don’t want to deal with him anymore. That’s what I’m talking about.

Groth: Yeah, yeah. Let me just say that I am thoroughly opposed to cancel culture. I find it odious and pernicious. And that’s not what we were doing, and that’s not what we attempted to do. I did think Shooter was sort of the poster boy for a semi-literate philistine buffoonish comic book editor at that time, with his kind of simple-minded views of what constituted a story, what constituted acceptable comics. A thoroughly mediocre editor who is imposing that mediocrity on his staff.

[00:05:00]

I mean there are two aspects to this, one is, whatever criticism we ran about him, and the other side was, journalistically, the sheer number of people that were angry for whatever reason. Whether they were angry for him firing them or letting them go, or in their opinion ruining the books they were working on and so forth.

He got a lot of heat, no doubt about it. But as I recall, there were an awful lot of people who defended him and… I haven’t paid any attention to him in a long time… But as of a few years ago, he still seems to have a fan base.

Alex: Yeah, he still has a fan base.

Groth: Years ago, he still has sort of a blog where he’s writing his revision as history, and he still seems to be sufficiently worshipped.

Jim: He has a voice, that’s for sure. And he does write his own way of telling all of that.

Groth: Yeah, his own view of history. So no, I think we probably just gave an alternative perspective.

Alex: I got you, and that’s good.

Jim: I have a question. Since Alex brought up cancel culture and then we’ll go back. I’m going to take this off the rails for a minute… Did you read this morning’s Daily Beast Story about the sex aspects of things?

Groth: No. I heard about it, but I haven’t read it yet. I heard it’s a good summary…

Jim: It’s a very good summary, it’s very cohesive and everything, but it links all of that to a lot of the things that you were worried about and talking about, when Comics Journal started. I mean it talks about Kirby and his art. It talks about pay and how people are cheated. And that sexual discrimination and sexual harassment are born from those labor issues of the earlier times, that it’s all part of the same mix. And I thought of you as I was preparing for this, and I read that. The question that I would come to from that is… Because I also know you signed the letter, this week or last week, about cancel culture and things… Didn’t you sign that petition?

Groth: I would have loved to, but I didn’t. I mean I wasn’t asked to.

Jim: Okay.

Groth: I would have though.

Jim: When these people are doing these things, the Warren Ellis kind of example, or whatever.

Advertisement

Groth: Yeah.

Jim: Where they have a long history of this. It’s not to say, that we should support cancelling but where do you stand on that, in terms of, do we just not talk about it? Do we let them go forward with it? Or what do you do? Is cancel culture a problematic go-to, just like PC was, years and years ago, where it becomes a way to distract from actually doing things that are important to accomplish. That would be my question.

Groth: I think you have to distinguish between the artist and his work. And I’m not intimately familiar with… I mean, I’m aware that Warren Ellis has been accused of a number of transgressions, and I’m going to read that piece… I mean it’s difficult, what you shouldn’t do is conflate the person with the work, and cancel the work. I don’t know if I’m trying to pick some… Everyone one of these is so unique to themselves so, it’s hard to choose anyone. But I mean, I guess what I object to is… Let me take an artist who I admire, who’s Robert Crumb.

Jim: That’s a good one.

Groth: He’s the poster boy of cancel culture. You probably know that a room at a convention in Massachusetts… I think the convention is called MICE. They had rooms that were named after cartoonists. They had Eisner Room and maybe the McCay Room, and they had the Crumb Room. They recently renamed the Crumb Room because he’s seen as a misogynist and a racist. Why the Eisner Room is still there, is something we should talk about.

Alex: Well, that might not be for, in the future.

Groth: Do you know that?

Alex: Well because there’s these people saying, with his character from the ‘40s…

Groth: Ebony, yeah.

Alex: There are people out there putting a petition to get rid of his name and stuff like that.

Alex: Right. That wouldn’t surprise me at all. Obviously, there’s this backlash against Crumb. And you’re probably aware that he was… His name, not even him, but his name was booed at the Ignatz Awards, like two years ago. I don’t think Crumb is above criticism, but I do think that it’s kind of mob mentality. This kind of reductionist mob mentality that fixates on one very narrow part of his comics career. It’s intellectually, and morally reductionist, and does not serve the purposes of viewing an artist in his entirety.

It is this kind of intellectual and moral reductionism that bothers me so much. That it’s focused on to the exclusion of everything else. And I’m not saying that that can’t be argued and that it can’t be debated.

Jim: We were talking about that at Comic Fest in San Diego, recently. Mary Fleener and I were on a panel. She brought up the Crumb example of exactly that, and people standing up and protesting, and saying they were going to leave if he was there. Things that seem just outrageous and very dangerous. Where it gets complicated is, when you’re not separating the art from the person.

[00:10:04]

But where you have editorial, something like Shooter’s misdeeds and handling of people while he was at Marvel. There isn’t enough art to justify that I mean editorial policy is a problem that has to be corrected. And if it’s not correct, if it’s not cancelled, because of how they’re behaving in their job which is what that is, I think that’s a different thing. And the problem is, it all gets conflated in to one discussion, sometimes.

Groth: Yeah, I’m not sure what part of Shooter you’re talking about…

Jim: No, he was just an example. I mean, just how he behaved towards people.

Groth: He was let go, right? He was eventually let got.

Alex: Yeah, ’87.

Groth: I think that was just like a corporate policy that he caused so many problems and then… I don’t know, they were tired of him. You know, the Trump Syndrome, you just get tired of them and you want them out. That’s something very different, I don’t really have much of an opinion about that. I don’t think Shooter was poorly treated by anybody really; he swam with sharks and… But someone like Crumb is a much more complex case. It’s the level and the tenure that I think literally, reduces the level of discourse in the world. And it’s what I just find so embarrassing.

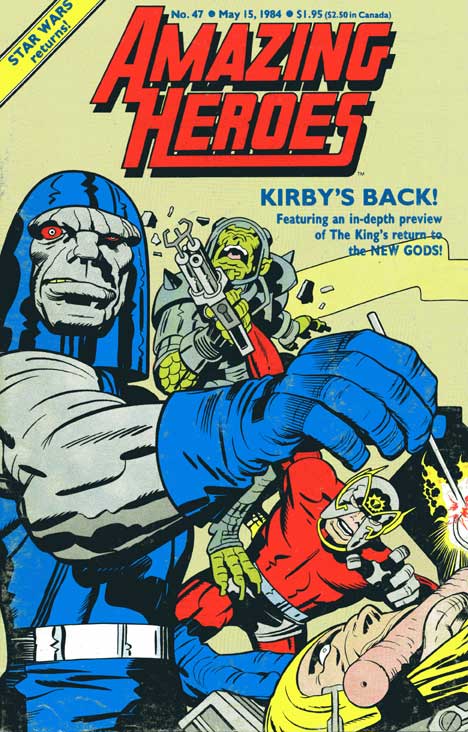

Jim: Well on a lighter note, how about that Amazing Heroes, Alex?

Alex: Yeah… Exactly.

Groth: Speaking of embarrassing…

[chuckles]

Alex: Okay, so again… Yeah, because you’re not into the superhero thing. Although The Comics Journal did provide the high-brow criticism that the industry probably needed, and I think to an extent, you help the comic industry grow up, to some degree. I think that that is true. But there was a shortfall in money. It’s kind of like when Bill Gaines couldn’t make money on the sci-fi, he was doing the horror stuff, you put out Amazing Heroes from ‘81 to ’92. It was more of a superhero fanzine, to make up for the cash deficit, and also kind of take maybe some of the fan base from The Comics Reader.

What was your perspective on doing that? Were you kind of biting your tongue with every issue? Or were you like, “No, this is, some of the fans like it. It is what it is”? I mean, what were you thinking with that?

Groth: Well, I mean we published some Amazing Heroes in order to bring in cash, so we could support the rest of what we were doing. And so, the question we asked ourselves… And this was roughly ’82, when it started?

Alex: Yeah, ’81 is what I have.

Groth: Can we publish a reasonably intelligent magazine about mainstream comics? And one that would bring in some cash. Kim [Thompson] edited it for most of its run, and this where we go back to Kim having a much more moderate view of comics.

Honestly, I never paid any attention to Amazing Heroes because it was entirely Kim’s baby. He edited it, and I would occasionally read a piece. And yeah, it did run some good stuff. I mean we would run interviews with Steve Rude, or Howard Chaykin, or a variety of other artists. They would certainly be on a better level than The Buyers Guide and all the other fan magazines that were out there. To me, it was just this thing that happened in another part of the office that I didn’t pay a lot of attention to.

Alex: I see. So, you weren’t that close enough to it to detest it.

Groth: No. I was detesting too much, you know, else.

Alex: [chuckle] As long as you’re detesting something.

Groth: It covered the whole mainstream arena. It covered it, as well as it can be covered, as intelligently as it could be covered, but my feeling was that… I didn’t even want that to exist. The less I knew about that the better. It was sort of oxymoronic to me to cover that area of comics intelligently, even though we were doing that. I mean I was a little schizophrenic about it, but we did all kinds of things like that in order to keep our heads above water. We were always, always on the precipice of financial ruin.

Alex: Yeah, and that helped to keep it going.

Groth: And Amazing Heroes was always… It turned into a bi-weekly. And it was definitely a profit center so, it helps support us through hard times and helps support us finance projects that we wanted to do. It was a really good steady money maker. And we never shied away from doing stuff like that. In 1981, ‘82, we published a couple of books called the X-Men Companion.

Alex: That’s right.

Jim: Yeah. I have those.

Groth: Which I absolutely have no interest in myself, but we figured, “Okay, they’ll make money.” Peter Sanderson edited them, we published them… I never really had a problem publishing stuff that made money that would allow us to publish work that we believed in and that would lose money. I accepted that very early on.

Jim: I have a question just real quick. As a person doing, not the Amazing Heroes, but the other stuff… As a divorce lawyer, I get used to people hating me to the point where it’s just- it’s part of the job. It’s almost a point of pride sometimes, because you know that you did a good job because of that. I was reading reports by people that were talking positively about you, but talking about how much other people in the industry- Marvel and DC detested you.

[00:15:02]

Where, if your name came up… I forgot who it was, but they were sharing a car with Bob Layton and with Jim Shooter, and the person defended you slightly… What was it he said… He said something about, “Their rectums tightened up so much that it was a reverse fart.” Barry Smith, I think.

Groth: That was Barry Windsor-Smith.

Jim: That’s right. What was that like? And do you miss it? Because you’re not hated as much these days, because of age or whatever. Do you miss it? [chuckle]

Groth: I do miss it, in a way. I mean, in a way, I’m quite happy. I’ve achieved a Zen-like calm. I don’t have to wake up in the morning wondering, what backlash it was going to be…

Alex: And you’re not wayward teen anymore.

Groth: Yeah, right. I’m a wayward dotard.

[chuckles]

I do miss it. I mean, you have to understand, I didn’t do that in order to be hated. It was just a logical consequence to what I felt I had to do. And I always felt like I was hated by the right people that was very important.

Alex: Right. If Kirby hated you, that’d be different.

Groth: Yeah, that would be devastating. But really, the people who hated me were the people that I had very little respect for and so, in that sense, it worked out very well. It was a very organic part of my life, walking into a room and figuring out how many people in this room hate me.

Alex: So, Amazing Heroes coming to an end in 1992, kind of like the way you had kind of suck some of the fan base from The Comics Reader. Was it in the ‘90s, there was so much of a glut of comics and magazines, and yada, yada; Wizard came out, did that basically contribute to the end of Amazing Heroes?

Groth: Yeah, Wizard, and I think there’s was a magazine called HERO Magazine.

Alex: Okay.

Groth: It’s kind of a mini Wizard. It was like a Wizard alternative. They were just far stupider than Amazing Heroes, and they therefore captured that market.

Alex: Right. Okay.

Groth: Our circulation was kind of going down… When I say Amazing Heroes was so profitable, I don’t mean immensely profitable, but by our meager standards, it was profitable. So, it went down, if the sales went down a couple thousand then it was a marginal, and no longer profitable. They just fade away.

Comics just became stupider and stupider. And the fact that the comics community, the comic fans, however you want to characterize it, they could no longer support a magazine like Amazing Heroes. I think it’s a great barometer for just how stupid the comics subculture became. You had The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, that was the beginning of the time when black and white became stupid.

Then you add Image. Now, I don’t know… I think Wizard came out before Image, if I remember correctly.

Alex: Yeah. I think of them as kind of together, for some reason, but yeah.

Groth: Yeah, I do too. But one had to be before the other. I think it was Wizard. But it was just this fucking locomotive of stupidity, and it couldn’t be stopped. I mean Image was sort of the apex of idiocy and hypocrisy.

Alex: Do you feel like Image got better though, like now?

Groth: Well, probably yeah. I know it transformed, of course. Honestly, I don’t follow it. Now, it seems like instead of just doing brainless Marvel knock off comics, they’re doing middle brow genre stuff.

[chuckle]

Jim: It’s how Chaykin can work, because he certainly isn’t going to get anything at Marvel or DC.

Groth: Well, didn’t he just do something for DC?

Alex: Howard kind of has been a victim of this cancelled mob as well.

Groth: Do you think so?

Alex: Yeah. His Divided States of Hysteria…

Jim: He thinks so.

Alex: Yeah, because we did a one on one interview with him, or rather two on one, me and Jim did. He goes into detail about that. He felt stabbed in the back by people.

Groth: I’d like to know more about that. I remember when that happened. That’d only happened like a couple of years ago, right? Three years ago?… I remember sending him an email saying, “Why don’t you tell everyone to go fuck off.” It seemed like he was treated shabbily by his publisher.

Jim: Yeah.

Alex: They didn’t speak up for him.

Jim: But they did publish his Hey Kids! book.

Groth: Well because it was safe. But I mean, they didn’t stand behind him when they needed to, when he needed them to.

Jim: No, a lot of creators didn’t either. I mean he feels very stabbed in the back by people that he thought he was friends with as well.

Groth: I can understand that. I was going to say, I think Howard thinks he’s more uncommercial than he is. I think he still has a lot of commercial cache.

Alex: Oh yeah, I love Howard’s stuff. So, one more question about The Comics Journal, then Jim’s going to go talk about publishing and things. So, The Comics Journal, and you were involved in some lawsuits with various creators…

Groth: [chuckles] Yeah.

Alex: Harlan Ellison, and Fleisher… First, we’re those scary for you at all? And then, two, just going through them, what can you share with us as far as surviving all that stuff.

Jim: And do you hate lawyers?

Groth: Oh my god, I hate all lawyers, except my own. I have a great lawyer. The lawyer who fought all that litigation for me, a stellar lawyer. I still speak to him about legal issues. It’s such a different period. It’s hard to explain to people who didn’t live through that and didn’t understand. We were sued three times within the course of about… I think they all came within 18 months. The first lawsuit suit was instigated in 1980, and then two more quickly followed.

[00:20:01]

I think they thought, they might as well jump on here. And I think the aim of these lawsuits was to put us out of business. They want to bury us.

Jim: Was Fleisher the first one?

Groth: Michael Fleisher was the first one. His lawsuit was based on an interview I did with Harlan Ellison, about which, we could have a separate videocast.

Jim: Can we? Because I would like to go into great detail about… Because you guys had a huge falling out over that, and then he sued you, and then it was in letter pages forever. I read everything about it through The Comics Journal.

Alex: Did you?… Okay, yeah. Knowing Ellison, you have to watch your back at all times. So, I interviewed Ellison… You know Ellison’s another guy… We should talk about people who I met and whose friendship and professional relationship I treasure and love, but Ellison… You know, I looked up to Ellison too, and did a long interview with him. And Michael Fleisher sued us based on that interview.

Ellison made a couple of assertions that could be either considered factor or opinion, depending on how you looked at it, and said that Fleisher, based on his work was crazy as a bed bug. Based on that, Fleisher sued us. He asserted that Ellison was saying that he was clinical insane, and damaged his reputation, as a result.

Then a short while later, Alan Light sued me for an editorial I wrote. This was on the occasion of Alan Light selling The Buyers Guide to that company in Michigan or wherever it was.

Alex: Yeah, Krause [Publications] or something like that.

Groth: Yeah, Krause. And it was sort of my farewell editorial, and I accused him of engendering spiritual squalor. He sued me for that. And then Rich Buckler, you remember Rich Buckler? He sued us for asserting that he plagiarized Jack Kirby. And that was an article written by Ted White, who I had previously told you, was our music columnist in Sounds Fine.

So, we had three lawsuits going on at the same time, and I was… When we were sued initially, I think I was 25, that would’ve been in 1980. I think I was 25 when Fleisher sued us. I mean, we were just scraping by. We had absolutely no money. We could barely just survive. We could barely pay out rent. It was maybe three or four of us comprising the company. We weren’t putting out Amazing Heroes… I think we’re only putting out The Comics Journal in 1980. So, it was only probably two or three of us working in this little office. And so, he sued us for $2 million.

I think you asked me if I was scared. I don’t remember being scared. I remember being exhilarated, and I remember thinking, we should win this, if we had the money to fight it. I remember being invigorated. I mean somehow, we just thought we were going to somehow win this. The problem is, we had no money. So, that’s a big problem… As a divorce attorney must know.

Jim: Yes.

Groth: So, Fleisher sued us first, a $2 million lawsuit. And I read about it. I think I read about it in Publishers Weekly. Before we were served, I read…

[chuckles]

Advertisement

… This notice that he sued us. I mean somebody brought it to my attention because I’m sure I wasn’t reading Publishers Weekly at the time. But somebody brought it to my attention and said, “Hey, you know Fleisher said he filed suit against you.” I say, “What are you talking about?” And he sends me the article, and I call up Ellison.

Ellison, in his usual bravado says, “Don’t worry about him. Fuck him. He’s not going to sue us.” And I say, “Well, it says he sued us.” “Well, don’t worry about it.” So, I said, “Well, you know I’m a little concerned about this.” And he said, “Don’t worry about it.” He said, “I’m with you in this. If he sues you, I am with you 100%. And I was saying, “Well, I don’t have any money to fight a lawsuit.” He said, “I’m with you. I’ll help.” Then he reassured me, I felt good about that.

So, a few weeks later, we were served and then Ellison was served. I didn’t know what to do. We didn’t even have a lawyer. So, I called up Ellison, and I said, “We’ve both been served.” I said, “What do we do?” And he said, “Well, you got to find a lawyer.” And I said, “Well, I don’t know how to do that. I don’t know how to pay a lawyer. Can you help us with this? You said you’re going to be behind us with this.” We’re on the phone, I’m in Connecticut. He’s in LA. I am freaking out a little bit and he said, “Look man, I’m watching TV. I’m busy I got to go.” And that was it.

I’m like on the phone… I thought this guy was behind us. He has money. He had just won like $200,000 from a lawsuit of his own, so I figured, when he said he could help us, he meant he could help me financially. So, I didn’t know what to do.

So, we hired a lawyer. We found lawyers in New York, and these were high powered lawyers. So, I employed them. I didn’t know anything about lawyers, lawyering, and so there were some initial motions back and forth. And I remember, about six months to a year in the lawsuit… And again, keep in mind I’m like 25, maybe 26, and I go into my lawyer’s office in New York. I go to visit him, and there’s some motions back and forth already, and this guy was like… He was a slick operator. This guy was smart, and he’d been around, and of course, I wanted to win this because there was a first amendment issue at stake.

[00:25:04]

He said, “Look…” He got me into a conference room; one of those big conference rooms with a 20-foot table. I sat there, and he said, “Look, we can get this guy in a deposition, and I can annihilate him, but he could still win. So, I think you should cut a deal.” And I kind of walked out. I mean I was just kind of in a daze, because here’s my lawyer advising me to cut a deal. So, that didn’t sit well with me, so…

I don’t want to drag this out too long… But I didn’t know what to do, so I called the Playboy Foundation which was Hugh Hefner’s First Amendment organization. And I talked to a guy there named Bert Joseph, who was a First Amendment advocate and he worked there. I explained the situation. I said, “I don’t have any money. We publish a magazine about comic books.” And he said, “What?” I said, “Yeah, comic books.” He said, “All right.” He said, “Here’s the name of a lawyer. First Amendment attorney in New York. Call him. I know him. He’s a friend of mine and he might take you on.”

And that lawyer’s name was Ken Norwood. I went into Ken’s office, laid the whole situation out for him, showed him the magazine, and he looked at it, and he said, “We could win this. I’ll do it. I’ll take it on.”

Then we had to figure out how to pay him. But he was a little loose about that, he said, “You know got to pay me, but we can figure it out.” So, he took us on, and we fought that lawsuit suit for seven years until we finally, in a jury trial in the Southern District Court of New York, won. It was a brutal fight. It was seven years of our lives. It was tremendous amounts of depositions, many people in the comics industry was subpoenaed, many people were deposed. We were subpoenaing people left and right. It just went on and on, on; the deposition lasted for weeks. The jury trial was four weeks long. It was just an amazing brawl.

Jim: Seven years is an incredible amount of time to be caught up, emotionally, in that.

Groth: Yeah. Well thank God, we’re young. And it divided the comics industry. Here’s what’s possibly more interesting, is that it divided the comics of history. It divided them into two camps, one was ours, and one was by default, Fleisher’s. And the reason people were supporting Fleisher… Fleisher really wasn’t part of the comics community; I mean nobody really knew him very well. He didn’t hang out with other comics creators. He wasn’t particularly liked, he wasn’t disliked but, he just wasn’t part of that community. But people wanted to see us destroyed, and so as a result, they supported him.

Jim: So, they weren’t on his side as much as they were not on your side.

Groth: Right. They weren’t on it for his side per se. They just hated us so much that he was a convenient bludgeon.

Jim: But you had to fight it, because the impact if you hadn’t would be, how do you do criticism of anybody’s work if you have to worry about getting sued for saying something derogatory about that.

Groth: Well, I felt strongly about that. First of all, of course, we’d go out of business, I mean there would be no Comics Journal.

Jim: But what happened to Harlan? Because he was named in it too.

Groth: He was there throughout most of the suit, and our falling out was due to certain machinations throughout the lawsuit. He was my co-defendant, but he was so utterly fucking treacherous that I had this one guy suing me, and I had a co-defendant who would stick a knife and my back at the nearest opportunity. I had to watch both of them.

Jim: He eventually sued you himself, didn’t he? Over something?

Groth: That was in 2006, I think. And that was about something else entirely, yeah. That’s a whole other story.

Jim: I could do this all day because I have all these follow up questions. In The Comics Journal, one of the things I respect most about it has been not just your lawsuits but other important lawsuits you have covered in a very smart way, that I could appreciate as a lawyer. Your depositions that you include, the transcript things like that, that nobody else does. And I think it’s very important to do.

I want to move on to the publishing part, rather than The Comics Journal part, although I wish we had more time to do both. Maybe we can do another interview.

Groth: I could bore your viewership into a blind stupor.

Jim: [chuckle] Two points on The Comics Journal, and then I’ll move… Three actually. Honk! I want to ask you about Honk! I have all the issues of Honk! and I really enjoy that. What made you do that and why was it not successful?

Groth: All I can do is tell you not enough people bought it. It was an oddball humor magazine published … Let me see, that’ll be ’85 to ’88, something like that… ’86 to, yeah, something like that. I mean it was just an oddball magazine that very few people at that time are going to buy. And success or failure depended on like a thousand people. I mean, if a thousand more people bought it, it would continue. And I don’t remember… You’d have to look in the… You don’t have a copy handy, I guess. Tom Mason who worked on our art department might have started that magazine. And if that’s the case, I think he edited it. Either he started it, and edited it from the beginning, or he took it over at some point.

[00:30:00]

But I think he just came to me. He was a designer, worked in the art department, and I think he just came to me and said, “I’d like to put this magazine together. And it’ll include this, and this this, and these kinds of artists. This is the direction, and what about it.” And sounded good to make.

Jim: I say it partly as a segue to what we’re going to talk about publishing because in the issue that I believe it was the one that had Warp Stuff as Smokeman on the cover. An interview there. It was a European comic, the name is escaping me of him, but it was about the giraffe, and it was playing with panels… You know the one I’m talking about?

Groth: Is this something we published?

Jim: Yes, this was in Honk!.

Groth: Okay, okay.

Jim: It was entitled The Giraffe, and it was like a nine-panel grid but the character kept moving around through the nine panels. It’s a famous European artist. There were things like that that we’re quirky… I’ll let you know who it is… I’m just blanking.

Groth: Yeah…

Jim: But you guys were introducing material that nobody saw anywhere else with that.

Groth: Could that have been Franken? André Franken.

Jim: Yes, it totally was. And you can’t see my books, unfortunately.

Groth: No, no. I can’t see your books though…

Jim: But you did publish this recently?

Groth: Yeah… [overlap talk]

Jim: You can die laughing…

Alex: But they do exist. The books do actually exist.

Groth: It’s like a Steranko effect.

Jim: Yes. I just want to say, you were interested in publishing, and I know Kim Thompson was a lead in a lot of this. But that’s something I want to talk about, that part… Before I leave Comics Journal, a couple of things… What was it like to actually get… We talked about people that liked you, they’ve got mad at you, or whatever. What was it like to get yelled at by Jules Feiffer, over your Eisner’s comments?

Groth: It was intimidating.

Jim: I’m a huge fan of Feiffer.

Groth: Me too.

Jim: It would make me cry if I got yelled at by him.

Groth: Yeah, it was intimidating.

Jim: And maybe we should explain to the listeners what I’m talking about. You had written something about Eisner that called into question his actual ability. Like you were critical of his actual art which a lot of people stay away from, to some degree.

Groth: Right.

Jim: And Feiffer wrote to you or did he call you?

Groth: No, this was in an interview I did with Jules. I wrote a review of three books by Eisner, and this was his post Spirit graphic novel phase, when he started doing A Contract With God in ’78, I think it was.

Jim: The Building, I think was one of them.

Groth: The Building was one them. They did a succession of graphic novels after that. I think my review appeared in ’89. It was review of a couple of his books, including his autobiographical book called The Dreamer.

Jim: Right, which other people are critical of as well.

Groth: At which, it was really truly a miserable book. I mean, just fundamentally dishonest. And I wrote as much. So, a few years later, maybe only a year or two later, I’m interviewing Jules, who was one of my heroes. Of course, I had seen Colonel Knowledge before I had seen Feiffer’s cartoons.

So, anyway, this was a big opportunity for me, I thought. I mean interviewing Jules. And Jules was, he was exactly the kind of cartoonist I wanted to get in The Comics Journal. I wanted to get outside of comic books, and I wanted to get out of comic strips, and want to do editorial cartoonists. And I wanted to do uncategorizable cartoons like Jules or Ralph Steadman.

That was important to me, so I was in Jules’ studio we were talking, and I forget how it came up. It seems like he must have brought it up because I don’t think I would have brought it up. But he told me that he thought I was wrong; my assessment of Eisner was wrong. And I defended myself, but I mean, it was a forceful attack on the review. He attacked and I defended myself. But I don’t think I expected that. He goes back a long way with Eisner.

Jim: From the beginning, yes.

Groth: Yeah. Eisner was the guy who hired him when he was 14 years old or something. And so, he has a great sentimental attachment to Eisner. I think that, more than anything else, is why he felt the need to the defend Eisner.

Jim: One other question. Just to go back to the lawsuits and things, as a journalist was it difficult for you, for The Comics Journal to be covering The Comics Journal? How do you, as a journalist write about something, when you’re in the middle of it, where you are part of the story?

Groth: Well, I don’t remember who wrote the news pieces about the Journal’s own lawsuits. I don’t know if we got anyone outside the Journal to do it. It never bothered me, the whole conflict of interest between us publishing books, and The Comics Journal reviewing books never bothered me, one wit. I always felt that I had the ability to stand outside of both The Comics Journal and our book publishing to be objective about that.

And I think that’s proven, if anyone, if any academic, has taken this on and it’s done a survey of all the books of ours that we’ve reviewed. I think they’ll find that we do not favor our books. So, I never had a problem with that. We got a negative review on a book that I love. We publish a negative review of Love and Rockets very early on. Because I wrote a very positive review of it before we started publishing it, and then we started publishing it. And about a year in we ran a very negative review of Love and Rockets, for example.

[00:35:04]

And I also had this, in retrospect, a naive view that the artists we publish were so good, and so, sort of incontestably good, that they wouldn’t care if we ran a negative review of their work. Now I think, in retrospect, that was not true. But I felt compelled to do that, like if we got a review in, unsolicited, and if it was a negative review of one of our books, and I thought it was intellectually defensible, not just a hatchet job, I would run it.

It was a difficult place to be.

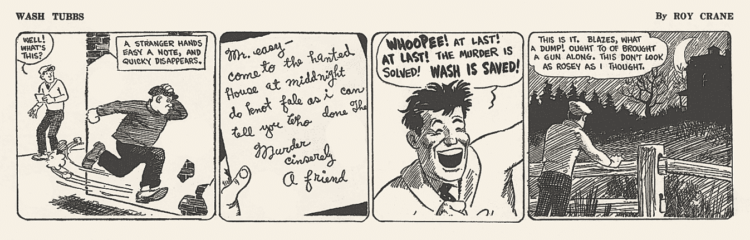

Alex: So, tell us about reprinting newspaper comic strips like Prince Valiant, and whatnot. First, how do you make something like that profitable?

[chuckle]

Because sometimes it isn’t.

Groth: Yeah, well your premise is false, you don’t make it profitable.

Alex: There you go.

Groth: I’m just kidding.

Jim: You made money on Peanuts.

Groth: Some of it is and so of it isn’t… Yeah, absolutely. Well, okay, here’s the thing, when we started publishing comics in 1981, Kim’s and my idea was just to publish great cartooning. It didn’t matter if it was European cartooning or old newspaper strips or contemporary work like Love and Rockets, to us it was just all a good cartooning.

So, we didn’t make a hard distinction between, this is our classics line, and this is this line, that’s line. To us it was just all a great cartooning, and that’s all we wanted to publish. So, Rick Marschall came on the scene in like 1980 or ’81, and he proposed Nemo to us; the magazine about comics.

Alex: Right.

Groth: Which we published 31 issues of and which he edited. Amazing magazine.

Alex: Yeah, and that was influential. There’s a lot of historian on the Facebook group that they were influenced by those.

Groth: It’s a tremendous monument to Rick’s knowledge and passion.

So, Rick bought a few books to us. We publish a Redbery Book, I don’t know why Rick brought Redbery Book to us, maybe he was in Public Domain or something. But we publish a Redbery Book. We published Popeye… I’m not sure if Popeye was Rick’s idea or was it Bill Blackbeard’s idea, I’m not sure.

Started publishing Popeye in like 1982… my dates might be off by a year or so. So, we started publishing Prince Valiant around ‘82. The reason we published all of these is just because we love great cartooning. We just wanted to publish good cartooning, it didn’t matter where it came from or what it was. So, to us, it was just all a part of the whole.

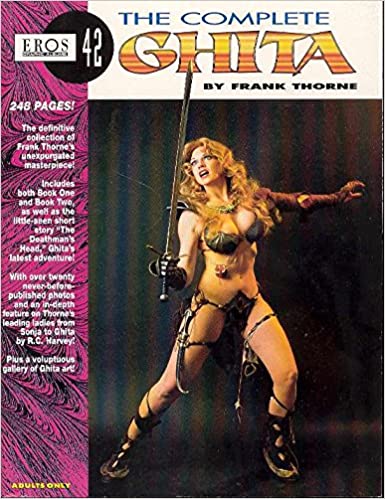

Alex: Now, as far as making up for stuff that is losing money, you talked about doing Amazing Heroes in the ‘80s, and we briefly mentioned it before. But in the ‘90s then, as Amazing Heroes goes to the wayside, you guys start publishing Eros, the pornographic comics to bring in some money. Does that basically, then help fund, and did it help fund as effectively as Amazing Heroes did in the ‘80s? Eros in the nin’90s to fund the other publishing ventures.

Groth: It was far more effective than Amazing Heroes.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Groth: We were losing money. We went through a period of like, I would say almost two years, where we were just losing ground. Starting around ’89. And I could see us losing ground, and I just couldn’t think of anything to do about it. Neither Kim nor I, we’re good at coming up with money making schemes. We just weren’t good at it. We were good at kind of guerilla publishing what we wanted to publish. But we weren’t good at just coming up with something that would make a lot of money.

If you look at most publishers, they always have these tent-pole projects that make a lot of money. We were just back sliding for year and a half, two years. We didn’t know what to do about it. We saw that was happening and we couldn’t figure it out. So, unbelievably, one day I just came up with this brilliant idea the sex sells. Just dawned on me.

Alex: Right, out of the blue.

Groth: I thought, “Well, shit, we’ll publish erotic comics.” There was Omaha the Cat Dancer that did well. God, I don’t know was Cherry around then? I mean, there were a few erotic comics. I think Chaykin had done Black Kiss by then.

Alex: Right, right. Yeah.

Groth: So, there were like a little sprinkle of erotic comics, and coincidentally, they all sold well. And it really took me a while to put two and two together.

[chuckles]

Maybe we should do this…

Alex: Martin Goodman would’ve jumped all over that, a lot sooner.

Groth: I’m surprised Al Goldstein didn’t… So, I talked to Kim about it, and we agonized over this decision. It’s like. “Well. should we do this?… It’s porn…” And I would talk to other people about it. Everyone I talked to said, “You know, if you have to do it, do it.”

I remember talking to Robert Crumb about it. I said, “Well, you know, we’re struggling with this. We might do this. I’m not sure… I’m not sure I feel good about this.” He said, “Jesus, you know get over it. Just do it.” I mean he was just so, “like what are you complaining about?”

Alex: Yeah, I don’t see how he would say no to that, anyway.

Groth: Right. I mean what he did wasn’t porn, but it was pornographic.

Alex: Would you say they’re similar to Tijuana bibles, what you guys did? I guess not.

Groth: Mostly not. No. What we did, it ran the gamut, I mean, if you studied Eros, it just ran the gamut.

Advertisement

Alex: I used to see those at Virgin Megastore when I was in high school. I didn’t buy any because my mom would get mad at me but I flipped through it.

[00:40:01]

I didn’t put it down, I mean, I was flipping through it.

Groth: Well depending on what you looked at I mean it could be just extraordinary.

Alex: Yeah.

Groth: If it was something like by Frank Thorne or Francisco Solano-Lopez, it could be really superb work, or it could just be weird brainless sex stuff.

Alex: Yeah, like orgies and stuff. I remember thinking, “I didn’t know penises could have these many veins.”

Groth: Right, or this person had these many penises.

[chuckle]

But we started it. We sent out a call. We sent out… I don’t know how we did it… What we did, there weren’t emails back then, so we sent out letters to cartoonists saying, “We’re starting an erotic line of comics, and if you have any ideas, and if you ever wanted to do one, let us know.” Well, apparently, there were all these repressed cartoonists out there.

Alex: Ready to go…

Groth: We were inundated with submissions. Frank Thorne was in the original wave. We published several erotic comics; I think it was 1991. And I am not exaggerating, in nine months, we had dug ourselves out of the hole. Nine months of publishing Eros comics.

Alex: That’s like direct market to stores and stuff, right?

Groth: It was the comic stores, who many of them created an erotic section that was composed mostly of our books, and we did a huge mail order business too. So, then we just went all in. We had an Eros editor, that became his division. As far as I was concerned, it was like Amazing Heroes. It was like this division I didn’t have to pay too much attention to it, we had an Eros editor. And we publish like mountain of filth. It was just an unbelievable tsunami of erotic stuff, and some of it was great and some of it was lousy. We just cranked it out, and that supported all of the grossly uncommercial alternative work that we wanted to publish during that period.

Alex: Yeah, and you guys were reprinting or have reprinted Barks, EC, foreign material like Crepax, and whatnot. So, it’s nice to have something that can fund that sort of artistic… Because you were introducing a whole generation of Americans to this stuff. To the good stuff, I mean, and maybe the bad stuff.

Groth: We are introducing a whole generation of Americans to pornography too.

[chuckle]

Jim: Is that why The Washington Newspaper gave you the Genius Award?

Groth: For which one?

Jim: One of them announced you were the genius of the moment or the genius something.

Groth: Yeah, I got the Genius Award. I mean for which one? Pornography…

Jim: For figuring out that sex sells. [chuckle]

Groth: Yeah, that’s it.

Alex: But you applied it in an effective way to survive and that’s admirable. I like that.

Groth: We did. We did. It’s just one of the few things we actually did, you could say Amazing Heroes was another one, and scattering of things once in a while, but that was a huge thing. The other thing you’ll learn, if you become a pornographer, every other phrase out of your mouth, is a double entendre whether you intend it or not.

Alex: [chuckle] So, your mind’s in the gutter all the time.

Groth: You can’t go three sentences without saying something.

When we were at the height, this is pre-digital, we had like piles of original art from… Frank Thorne, all these artists, and it was amazing… Robert Crumb. And we did seek out good work. I mean we obviously had to publish a certain amount of this stuff to stay afloat, but we really did seek out good work. We sought out gay erotica, lesbian erotica, good artists. Gilbert Hernandez did a book that was fantastic. We tried our best, but yeah, we were cranking it out.

Alex: But I wouldn’t call you a pornographer because it’s not like you actually got women in a studio and making them do stuff, right? That’s a different thing.

Groth: I use that term ironically.

Alex: But it’s a fun irony.

Groth: It took me while, but I got a kick out of it.

[chuckle]

It was all drawn.

Alex: Yeah, that’s true.

Groth: No one was exploited in the making of this.

Alex: Right, right. That’s the thing. That’s the key difference. Yeah.

Groth: A lot in comics…

Jim: On the subject of comic strip reprints, I got a couple of questions. I brought out Peanuts and I know that was a very profitable one, that you actually publish the entire run. There are others where I don’t know… Did you run out of steam with the Dennis the Menace books? Because I was buying every one of those.

Groth: I didn’t. I think the readers ran out steam.

Jim: I bought them all. The sales were going down, that was why the decision was made?

Groth: Yeah, pretty much. I think we’ve published five or six volumes. It really dropped like a stone. The first volume sold really well, and then you always experience a drop in series, but then you hope it plateaus and just maintains a decent sales level. And Dennis the Menace just kept dropping. I think after the third volume, most of the world had come to the conclusion that they had enough of Dennis the Menace.

I thought that was very unfortunate because I love that stuff, and I thought [Hank] Ketcham’s work was just extraordinary. The drawing is beautiful.

Jim: His line work is just so good.

Groth: It’s stunning. I mean everything about him, his gesture, the ink line, even the gags were good. Maybe they got worse later on, I’m not sure about that, but it wasn’t just a dopey panel, the gags were funny and they’re witty.

Jim: Does this mean I may not find out how Barnaby ultimately ends?

Groth: It will not mean that. I think the vast volume of Barnaby is going to the printer.

Jim: Oh, that’s great.

Groth: Yeah.

Jim: I’ve really enjoyed that as well.

[00:45:01]

Groth: Yeah, another masterpiece… I think the best thing Crockett Johnson ever did.

Jim: Yeah, and what about… Is Pogo selling well?

Groth: Pogo sells reasonably well, and we’ll continue that for the duration. Yeah.

Jim: Okay. So, Dennis the Menace was almost an outlier, in terms of that.

Groth: It was, yeah. I mean I can’t think of another… Well, Roy Crane, I can’t sell Roy Crane.

Alex: Which shocks me, because I love Roy Crane stuff.

Groth: Yeah, Roy Crane, is a brilliant cartoonist, but my god, we can’t sell him.

Jim: Do these books stay in print, and why do some go out of print? I’m specifically talking about the ones, of the Popeye volumes. There’s the one that I can’t get… Unless you can give it to me.

Groth: Of our Popeye series… I think there are eight volumes. I think seven are out of print.

Jim: Oh, now they are? I was victim of only one going out of print, I had all the others.

Alex: Yeah, but Jim, you’re talking about the one with the Jeep in it.

Groth: No. I think there might be more than that out of print. There might be a few copies in our warehouse, few volumes, but I looked at the inventory and they’re all almost all out of print. There’s only one we have a significant inventory on. And the problem is, you can’t reprint those. They’re too expensive to reprint.

Jim: And that would be my segue to something I’ve wanted to ask you since we interviewed the Trina Robbins and we were talking about Nell Brinkley… What is the reason that a book like that, that I think is so important … And I know there’s a new Flapper book coming up, but the Nell Brinkley book, I bought probably five copies of it, and gave it to people for holidays, and things. Every niece, every girl that I knew that a young woman, I wanted her to read that. Why isn’t that still in print? Is it just too expensive?

Groth: Well, the only reason that a book isn’t in print is because the publisher doesn’t think you can sell enough copies to warrant the reprint. And now you’re getting into a little bit of a minutiae here, where a reprint always costs more to print than the original printing.

Jim: Oh, I didn’t know that.

Groth: Yeah, because you’re going to be printing fewer copies. Okay, if you can print five thousand copies of a book initially, when you reprint it, you’re going to be printing two. And that’s because when you print a book initially, you have a big bump in sales. The minute it comes out, it’s going to sell a lot. And then it’s going to become a backlist, and it’s going to sell more slowly over time.

While when you reprint a book, you start off selling it slow. You do not have that initial sale. So, you have to be able to warrant the cost of a reprint by the sales over the course of 12 to 18 months. And if you can’t do that, you can’t afford to reprint that book. That’s really the only reason a book isn’t reprinted.

Jim: With the renaissance in printing of the important comic strips, is there something out there that you think that you haven’t gotten or no one has printed that you think needs to be done or have we pretty much completed the set?

Groth: I’m not sure. I think about this, of course, because I’m always interested in… One of the great joys of my job is to find new work, even if that’s old work. And I’m not sure if there much in the way of entire strips that need to be reprinted at this point. I think there might be some strips that you could put in an omnibus that ought to be available, but they aren’t up the first tier. They’re sort of like second or third tier strips but still display enough craft or enough wit, or ingenuity or something, that they ought to be available to readers who want to see them.

One thing, I think, is that there are number of artists out there whose work should be reprinted. Tomi Ungerer, for example, who I interviewed a couple years ago.

Jim: Yeah. I have that issue. I read his books to my kid; my seven-year-old.

Groth: Oh, do you?

Jim: I love those books.

Groth: Great children’s books.

Jim: From the early ones to Fog Island, and everything in between.

Groth: Yeah, Fog Island is terrific. We were reprinting his satirical books which are a particular favorite of mine. So, we just published his underground sketch, and we have a book of his called The Party. I think just went press. We’re getting his satirical books back into print.

Jim: Oh, that’s fantastic.

Groth: There are other artists like Robert Osborn. We just published Art Young.

Jim: I have that. You guys did a great job on that. That’s a fantastic book.

Groth: Are you talking about Inferno?

Jim: No, I’m talking about the other one that came out… I’ve ordered Inferno. I haven’t gotten that yet.

Groth: Yeah. I think there a lot of artists whose work should be put back into print, but it’s tough because there is only a limited number of people like you.

Alex: That’s true, and I can attest to that.

[chuckle]

Groth: Yeah, I bet you can.

Jim: Thanks, Alex. Let’s talk about people that you published over the years, that have made tremendous impact on us. Love and Rockets, obviously, is one of the most important books and creators that you published. Who else? Would it be Neat Stuff? Would it be Naughty Bits? Would it be Meat Cake, Jim up to Hip-Hop Family Tree, there’s so many things. What are the things that you’re most proud of?

Groth: I hate this, because I’m going to forget so, so many people, which I don’t want to do. I mean you mentioned Love and Rockets. I had no idea when we started publishing Love and Rockets that Jaime, and Gilbert would become two of the greatest cartoonists alive. I was excited about their work. I consider Love and Rockets our flagship publication.

Jim: Who knew it was going to grow?… I love the early stuff, but boy, they just went like a rocket off into other places.

[00:50:03]

Groth: They both did. I remember being so exhilarated by their work that was the kind of work that I was envisioning, as to what comics could be. They actually evolved into to that kind of work too. I mean I saw it in their earliest work but then they just grew in my own conception of what comics could be, which is a medium that directs its expressive possibilities toward the human conditions. Towards all of the things that are so… That are most important to us, in our lives. That’s what they do.

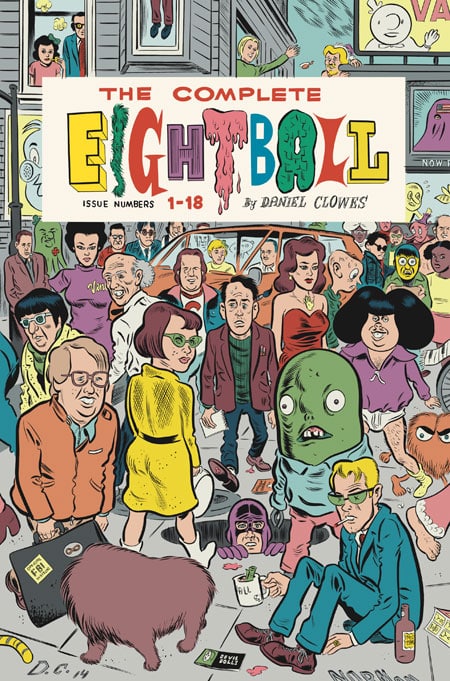

When we published Gilbert and Jaime, shortly after that we published Pete Bagge’s Neat Stuff and then Pete grew into one of the great satirical artists. Then shortly after that Dan Clowes. Dan started off with Lloyd Llewellyn. I saw such an absolute control over the media, and what he was trying to … I mean Lloyd isn’t great, I mean he went on. Dan went on to do great work. But what I saw on Lloyd Llewellyn was just that he knew what he wanted to communicate and he knew what he wanted to convey he did it perfectly. But I had no idea he could do anything more than that. And then he went on to deepen and broaden in his range.

Joe Sacco.

Jim: Oh, yeah. I didn’t mention him and I should have.

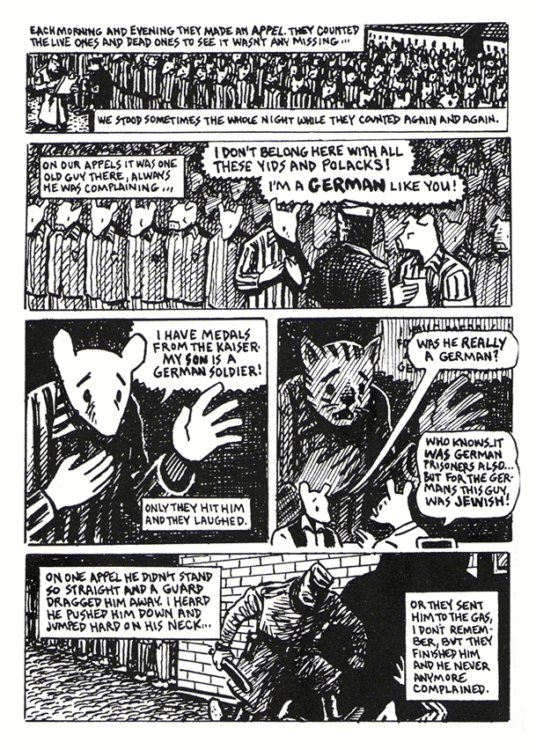

Groth: Joe worked in our office. He wrote news for The Comics Journal. He was a staff writer for The Comics Journal in 1985, I think. He would show us his comics, every once in a while, me and Kim. And they were okay. We started publishing Yahoo, his anthology comic around ’87, something like that, ’86, ’87. And there were short stories, and autobiographical stories, and he was really just kind of finding his voice. And then of course, he went to Israel and Palestine, and started drawing Palestine. When did that start? ’88, ’89, something like that. Anyway, he found what he was meant to do, which was comics journalism. And he virtually invented that category. Joe has been a good pal since then.

Kim is the one who discovered Chris Ware. he showed me his work in the Chicago Reader, it would have been around 1990, maybe. I had read Chris’ story in Raw before, but I didn’t actually put the two together. Chris did this kind of super hero-ey satirical take on superheroes. But then Kim showed me the work in the Chicago Reader, and I remember saying, “Well this is pretty interesting.” But it was Kim who really brought him in, and contacted Chris, and arranged for Chris to do books for us. I think we published… I don’t know, six or seven Acme Novelty Libraries before Chris went off on his own.

There’s so many. I mean, Carol Tyler, we’ve been publishing for a long time and she’s extraordinary. Boy, I think we published Aline, Aline Kominsky-Crumb in the late ‘80s. We published a collection of her work. I’m proud of the fact that we published a lot of women cartoonists in the 1980s when there were so few women.

Advertisement

Jim: Oh, yeah. did you do Julie Doucet stuff?

Groth: No, we didn’t.

Jim: That’d be Drawn & Quarterly, wasn’t it?

Groth: D&Q did Julie, think starting around 1990 or ’91.

Jim: That’s right.

Groth: It’s hard to believe, people in their 20s just can’t even consider this, but there were so few women in comics in 1980s.

Jim: You did La Perdida.

Groth: Sure, Jessica Abel’s work… Yes.

Jim: Jessica Abel’s work. Yeah, I remember that. That was great.

Groth: We published that, and I think we published two books by Jessica before that as well.

Jim: You brought up Raw. I wanted to ask you that. What’s the difference in your publishing philosophy? Or what you’re trying to put out there compared to what Spiegelman was doing? Because it seems, you’ve got some crossover like Gary Panter.

Groth: Sure.

Jim: Were you approaching a different notion of audience or a different kind?

Groth: Well, if Art did come to us and said, “I want you to publish Raw”, we would have published it in a New York minute. Because it was certainly the kind of work that we thought was inspirational. But Art has, Art and Françoise who co-edited it. They had their own very distinct sensibility, which might be more experimental and less narrative driven than mine and Kim’s was, I think. Which is kind of paradoxical because Maus is very narrative driven, but there was a lot of work in Raw. I mean in ranged.

I mean there were narratives, Kim Deitch in there, Charles Burns was in there. But there was work where the form took center stage and was possibly more important than the actual narrative. I think Art probably had a greater and more intense interest in form than we did.

Jim: Oh, that’s interesting.

Groth: I mean we did. We cared about the form, and I think we have published some more experimental work, but he really sought it out. I think if there’s any distinction between us, it’s probably his emphasis on form.

Jim: I asked you, in relation to comic strips, if there was other things you thought needed to be published or what? And there’s not the obvious missing greatness. Fantagraphics has started printing more and more European comics and foreign material.

[00:55:04]

What are the things out there that are your targets that you want to really, really cover besides the Crepax books, which have been great? What else are you looking for?

Groth: Well I don’t think I can cite specific artists we’re looking for. A lot of great cartoonists, have already been covered, like Hugo Pratt. I mean I would publish him in a minute but I think somebody’s publishing him, IDW or Dark Horse.

Jim: Jacques Tardi, you also have done his…

Groth: Jacques Tardi was Kim’s author. Kim said once that he thought Tardi was the greatest cartoonist in the world. I remember replying that, “Not as long as Crumb is around”. But we would have aesthetic…

Jim: Oh, that’s great that was your conversation?

Groth: Yeah, yeah. But I love Tardi, I want to make that clear. But that’s how big an admirer Kim was of Tardi. So, Kim started publishing Tardi, and we’re continuing doing that. Tardi has a lot more work. We have two books in house right now by Tardi, and he’s certainly one of the great European cartoonists.

Crepax was someone I was very happy to publish. I was familiar with his work for many, many years ago, but his work had been so… Catalan, I think it was, published a book of his called The Man in (From) Harlem and that was a fantastic book. No erotica whatsoever. It was just a drama about the situation in Harlem. And so, I was a big Crepax fan, but most of the big historic European cartoonists, I think, have been published here, or are being published here.

Jim: Not European, but I want to see (Alberto) Breccia get a full publishing of everything.

Groth: Oh, yeah, well he is. We’re publishing all of his work.

Jim: He’s probably my favorite.

Groth: Well, he is a genius. Stylistically, he’s breathtaking because he doesn’t have one style, he has multiple styles. I mean he is so… Words fail me. I mean, he’s just so amazing. And every single book he does is so stylistically distinctive. He is masterful, the works in themselves, each individual work, is extraordinary. So, far we’ve published Perramus, and we’ve published Mort Cinder. And we have The Eternaut 1969.

Jim: Can’t wait for that.

Alex: Yeah.

Jim: Alex like gave me the German copy translation, so I actually have the work, but not in English.

Groth: Oh, you do. Yeah.

Alex: I like both Eternauts. Although there are some stuffs after, but that ’69, it’s not as long as the first one, but it’s beautiful panels. And I actually had to type it in German to English in Google just to kind of get what was going on, but it’s good.

Groth: But soon you will.

Alex: Yeah, exactly.

Groth: I mean, Breccia’s an artist that… We published Perramus in the ‘80s. Kim spearheaded that. We published four issues of Perramus, I think they were 48-page magazines. And here’s a funny little story. So, I wanted to publish the whole book Perramus, and I’d read our own four-issues series of Perramus when we published it in the ‘80s. And so anyway, we got the license to publish all of Alberto Breccia’s work. So, Perramus is on the list, I thought, “Okay, good. We’ll publish Perramus. It’s already translated.” Kim translated it when we published it in the ‘80s, and what he translated was about 180 pages. So, I’m digging in, and doing my Breccia research, and I discover, it’s only one third of the book.

[chuckle]

And I never knew that. I assumed Kim knew that, but never told me. And I don’t know why we didn’t publish the rest of it, maybe wasn’t selling that well. But Kim had his own reasons. But I thought it was the whole book and it wasn’t the whole book. So, we had, of course, to re-translate the entire books. We had not had the head start, I thought we did. But I’m excited about Breccia, but I’m not sure there’s anyone else of his comparable stature that’s out there. I’d love people to drop me a line let me know.

And right now, we’re looking at more contemporary work. I mean we publish cartoonist Manuel Fiore; we publish Giuppe, a lot of European cartoonists that we’re publishing, a couple of South American cartoonists, of course, a very slim but selective Manga line.

Jim: What’s the one, Wandering Son?

Groth: Wandering Son. Yes.

Jim: I have those. I like those quite a bit. They’re very good.

Groth: Eight volumes, yes.

Jim: Well, I could do this all day.

Alex: I want to ask some money questions, since I’m relegated as the porn money person…

[chuckle]

But I want to continue the theme a little, so in 1977, I read a couple like landmarks as far as Fantagraphics was about to fall apart, and then money came in to basically save the company. So, in ’77, Kim Thompson came in, using his inheritance to keep the money afloat. In 2003, Fantagraphics almost went out of business, a former employee said, it was financially disorganized. And then fans contributed with a lot of orders to get it back up into the positives. Then Kim Thompson died in 2013, there’s a void at Fantagraphics. And Kickstarter brought in 150,000 into the company.

First, are these correct statements, and then second, is that just kind of always a concern? And is this a repeating thing that you just always have to do? And that fans have supported you. What’s know what your take on all that?

Groth: I think it was all more or less correct. I mean I’d love to add some nuance, but you miss about two dozen other crises.

[01:00:03]

Alex: Right. There’s a lot.

Groth: It’s always been difficult. It got a lot easier when we started publishing Peanuts. Peanuts was a regularly published book, and that helped us lot. Prior to that, it was just economically debilitating. We were always under the gun. We would go for a year or maybe two years without suffering any financial problems, but then we would always hit a wall and we always had to figure out something to do to make enough money to keep going. The ones you mentioned we’re probably just the most acute financial crises.

Alex: Yeah, sudden and then there’s a sudden fix.

Groth: Because there were numerous, numerous financial problems… You have to understand that neither Kim nor I were business people. We didn’t have a clue about business. It was all by the seat of our pants. We had to learn how to do this. I had to learn how to read a P&L statement. I had to learn cash flow. It was all intuitive, and we never had any master plan. And I think Kim and I were both temperamentally unsuited to be in a position of business. But it was the only way we could fulfill what we wanted to do. We wanted… like originally, I mean, Kim came on after The Comics Journal started but he was fully on board. And we wanted to create this magazine of criticism and serious journalism, and the only way we could do it is by creating it ourselves. That meant creating a business.

Alex: Are you more of a business person now than you were?

Groth: Yeah, if nothing else by dent of the fact that I’ve done it for so long, and I can navigate these difficulties.

Alex: Yeah. So, just out of necessity, you’ve had to kind of become more the business person that used to be.

Groth: Yeah, it’s by necessity. I don’t love it. So, people love business, and I’m not one of those.

Alex: Last question from me, that I have is, I’ve talked to other people who published magazines with interviews, and I’ve heard of stories that they would… Let’s say tape, and because they didn’t have enough tapes, they would tape over someone else’s interview with another person’s interview just so they can get the transcript in. Do you actually have every audio taped interview that you’ve done? Or most of them?

Groth: We have most of them. There might have been a few that have been lost, but we have hundreds and hundreds of tapes.

Alex: What do you plan on doing with all those?

Groth: Well, we’re digitizing them now.

Alex: Okay, so you are doing that.

Groth: But it’s a long process, and it’s a lot of labor, and we have limited resources. So, it’s a very slow process. It stops and starts, and stops, and starts. Yeah, we’re just keeping them. I mean we’re keeping them safe, and we are digitizing them.