Comic Book Historians

As featured on LEGO.com, Marvel.com, Slugfest, NPR, Wall Street Journal and the Today Show, host & series producer Alex Grand, author of the best seller, Understanding Superhero Comic Books (with various co-hosts Bill Field, David Armstrong, N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., Jim Thompson) and guests engage in a Journalistic Comic Book Historical discussion between professionals, historians and scholars in determining what happened and when in comics, from strips and pulps to the platinum age comic book, through golden, silver, bronze and then toward modern

Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians.

Read Alex Grand's Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland & Company here at: https://a.co/d/2PlsODN

Series directed, produced & edited by Alex Grand

All episodes ©Comic Book Historians LLC.

Comic Book Historians

Tony Puryear Afro-Futurism Interview Part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

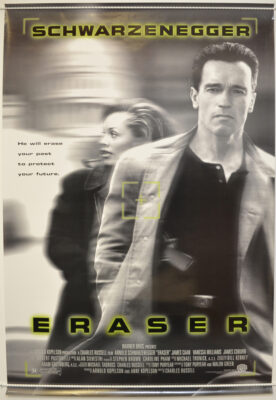

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Tony Puryear, Hollywood screenwriter and Comic book writer/artist, discussing key phases of his diverse career, from his childhood encounters with Jack Kirby & Phil Seuling, his advertising career under the mentorship of James Patterson, directing music videos for 80s hip hop stars, becoming the first African-American screenwriter to pen a $100 million grossing film, Schwarzenegger’s “Eraser,” intertwining his art with political activism in the 2008 Hillary Clinton campaign, partnering with post-Marvel Stan Lee, and co-writing, drawing, coloring and lettering the critically acclaimed Afro-futuristic comic series, Concrete Park. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand.

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians.

#afrofuturism #concretepark #eraser

Alex: Welcome again to the Comic Book Historians Podcast, I’m Alex Grand with my co-host Jim Thompson. Today we have a very special guest, Mr. Tony Puryear, who has a very diverse and extensive career; first as a chef, then in advertising, directing music videos, writing films for Hollywood, and also being an artist and co-writer on his hit comic series, Concrete Park. Thank you, Tony, for joining us today….

Tony, thanks so much for joining us today.

Puryear: I’m happy to be here, you guys. Thank you.

Jim: So, let’s start at the beginning. You grew up in the Bronx. Is that correct?

Puryear: No. Actually, I’m from Queens, in New York.

Jim: You’re from Queens, you went to school in the Bronx.

Puryear: I went to high school in the Bronx… So, in that regard, I am like the rep who currently represents that district, Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez who represents both, a piece of the Bronx but also Northern Queens, where I grew up. I grew up in a neighborhood called Corona; East Elmhurst, Corona in Queens.

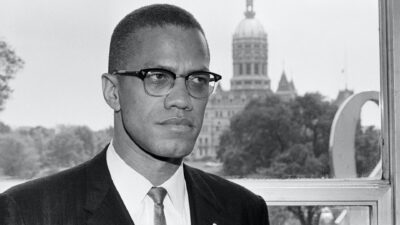

I’m 63 years old, so I’m old enough that Malcolm X was our neighbor down the block.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Puryear: And Malcolm X died in 1965, so that really dates me, but we knew Malcolm X. Also, I knew Louis Armstrong. Because Louis Armstrong lived in our neighborhood, lived in Corona. That was a great honor. I only realized years later how awesome he was. We knew him as the local celebrity, Louis Armstrong.

I grew up in Queens, went to high school in the Bronx, this high school called Bronx Science. So, it’s a big commute, you’d have to take the subway; a long way. I’m a bi-racial kid at the time when there weren’t as many bi-racial kids as there are now. My dad’s black, my mom’s white; we live in a black neighborhood in Queens. The white side of my family, my mother’s family, had disowned her for marrying a black guy. They told everybody she was dead.

So, I grew in a black context, I went to segregated schools. You have to understand, I was born before the Voting Rights Act was enacted.

Alex: Your parents got together in the ’50s? 1950s then?

Puryear: Yes, they did. They were married in 1955. You understand, their marriage wasn’t even legal in the United States, in many states of the union till 1966; I think with the Loving decision.

Jim: Yeah, that’s right?

Puryear: So, we lived in New York, which was very accepting, and very polyglot, and mixed-up. My old neighborhood now is very Latino, and is Indian, and everything else. But back then, it was a black neighborhood and we were very accepted. Yet we never traveled South. We never went to visit the south or anything because my parents’ marriage was illegal and bad things could’ve happened.

So, in that regard, I’m like Obama, Obama’s born the day before me, on August fourth. My birthday just passed, it’s August fifth. So, his parents were thinking along those lines too, obviously. He’s a little older than me.

Alex: That’s true.

Puryear: But in my time, that marriage was not so popular or common.

Alex: And you came out very light…

Puryear: Very light.

Alex: But with that and with your light eyes, you identify as African American, is that right?

Puryear: Absolutely. And it’s very funny, on Zoom, I come out very, very pink but either way, I’m light. Look at me…

[chuckle]

Jim: Yes.

Puryear: I’m like this old secret agent of blackness because I could pass or whatever, but that was never a life choice. I could have made it. It was the ‘60s. I mean you have to understand, my first school was a segregated school; de jure, by law it was segregated. By 1964, integration came to the North, I was literally in the first busing in the north which eased racial integration. I remember the white parents throwing garbage on us and everything.

Alex: Wow.

Puryear: So, my life choices were kind of made back then. I was a black kid. And of course, New York City is full of black people, ‘who look like me’. What is race anyway? It’s like a weird social construct but because of the times I come from, I’ve always identified as black.

Alex: There’s definitely cultural aspect to that. There’s an ethnic aspect. So, it’s not just the color of the skin, a lot of time.

Puryear: Yes… Uh-huh.

Jim: So, Tony have a question, before going back into like early comics and things, it’s related. How was it when your ex-wife Erika would say to the press, things like, “He’s the blackest white man I’ve ever known” and those kinds of things. Sometimes, you get labeled as white. Does it bother you at all?

Puryear: No, no. As I say, I should write a book because race is this interesting social construct in America. I just read a beautiful article by a light skinned black woman, who was talking about taking down confederate monuments. She said, “You want to see a confederate monument, look at me.” She said, “I have light colored skin.”

There’s this weird reason, because of slavery, because that one drop rule where if a child had one drop of black blood, they were black. Well, that obviously served white masters who needed as many slave bodies as possible. So, that old master can have several bastard black children, they all became his slaves no matter how light they were, etcetera, etcetera.

I come from a line of lighter skinned black people, but again, race being a social construct, but also a social category and a cultural category. Yes, I grew up identifying as a black child, the school integration did that to me as well. I don’t of mind whatever people want to call me, that’s fine.

Jim: That was a great piece on the “I’m a confederate statue”.

Puryear: Yes, here I am. I’m America’s legacy. Most black people in this country have some mixture of white in them.

[00:05:00]

Jim: So, when you were growing up, did you face any prejudice or any issues on the other side? Were you ever derogatorily called white by others?

Puryear: No.

Jim: You were fully embraced.

Puryear: I was very lucky, and the black community has traditionally been embracing by large. I’ll hear light skinned black people say, “Oh I had a tough…”, that wasn’t my experience. I was a lucky kid. I grew up in a context… New York City, I mean there’s lots of Puerto Rican kids who look like me. There’s lots of mixed kids in New York and the black community was very accepting. So, I never had an issue on that side of the street. No.

Jim: Yeah, I’m about the same age as you, one or two years younger. And I grew up in Richmond, Virginia where those statues are.

Puryear: Oh my god!

Jim: So, in my mind they all talk about preserving history, to me taking them down is the historical moment. That’s the thing that’s history.

Puryear: Exactly right. History is a continuity. It doesn’t stop in 1865 with the demise of the Lost Cause and all that stuff. No, no, no, no. History goes on. I’m history, and what I do here matters. What we do here matters. That’s history too.

Jim: Let’s talk about comics for a little bit…

Puryear: Yes, sir.

Jim: Because I know the time period that you’re coming on because it’s not different from mine. When did you start reading?

Puryear: When I was a little kid, there were comics in the barber shop. There were comics everywhere. There were comics at the drug store and comics at Woolworths? Remember Woolworths and all that kind of stuff?

Jim: Oh, yeah.

Alex: Is this the early ‘60s then?

Puryear: Yes, sir. I grew up loving comics. From a very early age, I was a Marvel fan, and not a DC fan. I found the DC Comics of the early ‘60s to be very corny. Lightning Lad and those sort of 20 stories…

[chuckles]

The imaginary stories they had to have Superman having you… “What if Superman was married to Lois Lane?” All that kind of stuff. I thought the Marvel Comics of the early ‘60s, of course, this was the Silver Age, they were amazing, and they were cool. The superheroes operated in a recognizable New York City, and I loved that. I love that there was Spider-Man swinging through Manhattan. There was the Fantastic Four, they had a building. To me, that was very grounded, very real, they all had problems, etcetera. I was a Marvel guy from early on, in the early ‘60s.

Alex: Did you like the Kirby-Ditko aesthetic? Were you looking for any particularly thing when you’re looking at that stuff?

Puryear: At the time, at first, I didn’t recognize the names of it all. Didn’t mean anything to me. But the Marvel Comics also has a certain look, and to me that was all Kirby, Kirby, Kirby. The way Fantastic Four looked. The way Thor, swinging his hammer, could reach all the way back, way back here in a way no DC superhero ever did. Because they drew from a very square sort of proscenium arch looking at Superman. Superman back then was being draw by people like Wayne Boring and…

Carmine Infantino was about as good as it got in DC comics. I mean, he’d have the Flash running like this. But that was nothing to the amazing perspective, the amazing cosmic feel of Thor, and Fantastic Four and all those comics. It’s amazing how many of those comics Jack Kirby was drawing in any given month… But that’s the look I like. I later realized who it was that was doing all that.

Jim: Your parents were both artists?

Puryear: Yes, but my dad worked as a salesman. My father was a liquor salesman, and he was a black guy who’d go out into black markets in places like Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit; these for his markets. Buffalo the real tent towns of the Midwest. And my father was the guy from the head office, who’d come out to the liquor stores and wholesalers in the black market, and say, “Come on, we got a special two for one on Dewar’s White Label Scotch.” That’s what my father did. He’d been a photographer. He had been a photographer in World War II. He was over there in Europe; he landed at D-Day, all that stuff.

My mother went to art school. She went to what was then called Carnegie Tech. She went to school there with Andy Warhol. She was from that generation, back when his name was Warhola you know, Polish kid in her arts school…

Alex: Yeah. That’s cool.

Puryear: They both were artist, and so I could draw from an early age. They always had me making stuff up and doing stuff with my hands. So, that was my background, yeah.

Jim: But at the same time your Mom wasn’t thrilled about your interest in comics, right?

Puryear: You’ve got my whole biography here, somehow. You’re like probably from the CIA or something… That’s exactly right. Like many kids of that time, I would take my allowance and I was supposed to get my new milk or whatever at lunch, or what have you, at school, and I would go and buy comic books. Then I’d have to hide them from my mom. And every mom who’s ever had a boy kid knows that the kid is hiding the comics under the bed or somewhere in the closet. They on to me, but we have this sort of charade, where I would hide the comics and my mother would tacitly, I guess, go along.

Jim: You’ve talked about Kirby it seems, like more than Ditko or Romita, or any of the others. We’re going to get to that more when we get to Concrete Park because I think Kirby is a huge influence.

Puryear: He’s a huge influence. And I knew him as a kid so…

Jim: That was what I was going to ask you. I had read that you had met him as a kid in New York?

Puryear: Yes, sir.

Jim: Please tell us about that.

Puryear: Okay, somehow the interest in comics kept all through… I’m talking about 10, 11, 12 years old, those key ages. I started to realize who was who, as far as on the method. I like the Ditko work a lot too, and I loved… Ditko had like the most incredible hands in the whole comic book business. Like when Doctor Strange would cast his spell. You know the Ditko hands, right?

[00:10:02]

Jim: Absolutely.

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: When Spider-Man would shoot the web.

Alex: Yeah, it’s perfect.

Puryear: I like the Ditko stuff very much too, and he only did a small run really, when you look at the whole industry. A small run on Spider-Man, who was amazing. And everybody knows the Ditko thing where Spider-Man is lifting the giant piece of machinery, you know he has to…

Alex: Right.

Puryear: Great. I love all that stuff… And Doctor Strange looks so scary the way Ditko drew him with his narrow face. He drew him like a super villain, to me.

Alex: Yeah, like Vincent Price or something, right?

Puryear: Yeah, yeah. But the stuff I like. the stuff that caught my imagination as a storyteller, as a kid, was Kirby, Kirby, Kirby. Tales of Asgard, amazing. And they used to sell these little paperback books. They’d be about this big, The Collected Tales of Asgard, for instance, and in black and white. And even in black and white, the artwork was so dynamic.

So just to make a long story short, by the time I was in junior high school, and then high school; I’m talking about 1971, ’72, ’73. They were having some of the first New York Comic Cons, and really, these were crude, crude affairs where people just sold crates of comic books. That was really it. It’ll be in some crummy hotel. There was a hotel that’s built next to Grand Central Station. It was called the Commodore, after Commodore Vanderbilt. It’s now Trump blah, blah, blah, Trump International or something. Trump bought it in the ‘70s.

But back then, it was a crummy smoke-filled hotel. People smoked indoors it’s hard to even breath. Conjure that world… But they would have these Comic Cons and they’d have these guys with their racks and racks, or crates and crates of comics. Then they would also have ballroom events in the hotel. There you can see Jack Kirby, and he would speak.

Alex: What year do you think this was?

Puryear: ’71, ’72?

Alex: Okay, early ‘70s.

Puryear: It was the guy, Phil Seuling who would have these big Comic Cons.

Alex: Yeah, so this was the Seuling convention then.

Puryear: Right. And I knew Phil through a kid who I went to high school with. But even at the time, like ’71, so I was still in junior high, Kirby would speak. Kirby had this really weird backwards way of talking; that didn’t make a lot of sense, I got to say, as a kid.

Alex: Yeah. Like Yoda or something.

Puryear: Right. The one thing I ever heard him say that made sense was, “You know, when you and I get angry, we kick a can down the street or something. When Thor gets angry, he knocks the top off a mountain. That’s the whole thing.” He says, “Look at The Hulk, he just gets mad all the time.” Well that made sense, but a lot of stuff Kirby said, I couldn’t even can follow it because it was very non-seq or whatever.

But you could also see him half an hour later in the room with the guys with the crates of comics. He’d just be standing there holding court, and kids like me would bring our drawings, and he’d look at them… And my drawings were awful… And he’d be encouraging. He’d say, “Yeah, so yeah try a little harder. I think you’re lazy. You have to… Like that. “ So, he was a real mentor figure to a whole flick of kids, and we’d go day after day to see Jack Kirby. It’s just a subway ride away for me on the #7 train. So, I would see Jack Kirby.

Can I tell you a Jack Kirby story? I’ve told this…

Jim: Please… Absolutely.

Alex: Please.

Puryear: One day, we’re in one of those rooms, he smoking a cigar, everybody’s smoking. It’s a little room, and these guys with crates of comic books. And New York being New York, there was always some edge of violence. I’m there, showing Kirby my drawings, suddenly from across the room you hear someone say, “Mother fucker!” And then, boom, boom, boom, and you hear the sound of a flight. Just boom, and the violence fills the room. Someone was stealing a comic or something, and two guys are a punch off. On the carpet, this ugly stained carpeting, they’re fighting and they’re grabbing each other shirts like men do. There’s blood coming up, and Kirby…

Advertisement

We’re all, for a moment like this, were frozen. I’m a little kid, and I was short for my age. And Kirby, who was very short… Kirby goes… He takes me by the hand, he goes, “Come here. I think we can take these guys.”

[laughter]

“I think we can take these.” I’m like terrified. I’m a kid. He pulls me across the room… This is a true story… And he confronts these guys. He says, “Hey, why don’t you guys pick on someone your own size.” And he meant it. He absolutely meant it, like he would fight these two guys right then and there. And because he was Jack Kirby and because he had that authority, because he had gray on his hair, and for a lot of reasons, they stopped.

Alex: He was probably 45 or something at that time?

Puryear: He was born, I think, 1917?

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: So, he’d be 53, 54.

Alex: 53, 54, okay.

Puryear: Poor little guy with a cigar, but just as tough as hell.

Jim: Oh, that’s great.

Puryear: An authentically tough guy. And he says, “Why don’t you pick on somebody your own size.” A line of dialogue from a Cagney movie, as corny as that. “Why don’t you guys pick on somebody your own size.” They stopped the fight and then they carry on and everything, and Kirby, we go back over and start talking about comics and drawing. At that moment, I thought he was god. He walked on water, to me. That was my idol.

Jim: When you came out here in 1990, to Los Angeles, did you look him up? Did you see him…?

Puryear: No. I didn’t think to, at all. At that time, I was very much in this ‘movie head’. I had been directing music videos back in New York. And so, when I got here, I was so happy, and I was living in the valley, working for Disney, then I moved to Venice. To this day, I don’t drive. I don’t know how to drive. I never learned how.

Jim: I was just going to ask you that because Variety mentioned that in their article in 1995.

Puryear: Yeah, yeah, never learned how to drive so it didn’t even occur to me to go out to where Kirby was in Thousand Oaks, or any of that stuff. No, didn’t do it and I regret that.

[00:15:02]

Jim: Okay, so when do you sort of age out of comics as a kid? High school or…? Did you follow Kirby over to DC, when he made the move?

Puryear: Oh, man. I thought that was the greatest thing ever. I remember writing papers in high school at Bronx Science, I was a very dis-affected kid. By that point, I wasn’t going to a lot of high school, I was a real truant. I was a real trouble maker. I was spraying my name on… Bronx High School of Science, if you look at it, it still is diagonally across the street from what was then called the Pelham Subway Yard, where they parked all the #6 trains, and then all the IRT trains were parked right there when it was the 1870s. We’d sneak into the subway yard.

So, I didn’t do a lot in high school, but the thing that engaged me was English class and sure enough I was up here writing papers, and then homework about the new gods and all that stuff. I thought that was great.

Jim: That’s really interesting because I had read where you said you trained yourself to not draw like Kirby. That it was important to you…

Puryear: Yeah.

Jim: Not to do that. And I mean this is a compliment. I think you write like Kirby in some sections.

[chuckle]

There’s a quote in Concrete Park, “The stranger’s too fast, too strong. Kill him and kill Silas for wealth and power.” And it’s like the cadence of that, and the rhythm is so Kirby-esk.

Puryear: Thank you. I never would’ve have thought of that. But that’s a good point. That’s true. People talk shit about how he wrote the Fourth World comics. I thought they were great. I thought the P.A.C.K., are you kidding me?

Jim: Oh, yeah. No, absolutely one of my favorite comics of all time. And there you have it, you read that dialogue, and just for a couple of parts, it’s there.

[chuckle]

We’ll talk about it later, but the other part you do on that, is when you get to the gate.

Puryear: Yeah. The Kurtzberg Gate.

Jim: The Kurtzberg Gate. I think it’s not really… I mean obviously, it’s not a gate. It’s a person but I think it’s almost you having to face the Kirby heritage.

Puryear: That’s exactly what it was. You hit the nail on the head because, it’s just what Miles Davis would say about Louis Armstrong. Louis Armstrong played more horn than anybody else has ever played. And if you pick up that horn, you must deal with that giant mountain in your road which is Louis Armstrong. You can go against him, you can go with him, but you must deal with it. Black people have this great expression in the black church, that you’ve heard repeated in R&B songs, when speaking of God, they say, “So tall, you can’t get go over him. So low, you can’t get under him. So wide you can’t get around him. You must come in through the door.”

And so, the Kurtzberg Gate is my way of saying, “Kirby is there on the road, you must come in through the door. You can’t get around him.”

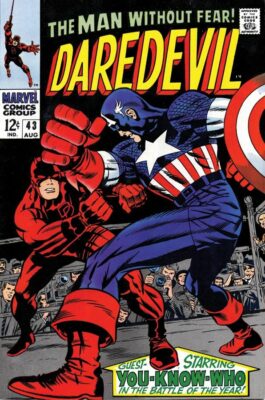

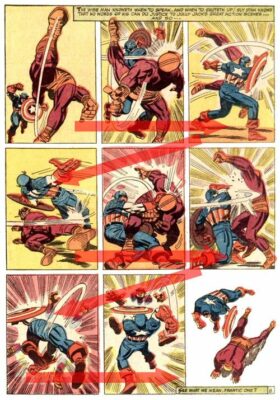

Jim: And you do it with the nine-panel fight grid.

Puryear: Yes.

Jim: That is so iconic. I saw that, and I was like, I know exactly what he’s doing.

Puryear: Thank you. And that was an amateur’s crude attempt. You’re exactly right. Just sort of process that, that thing of Captain America fighting Batroc.

Jim: Yep.

Puryear: Unbelievable. The Two-Gun Kid, I think, gets one like that too.

Jim: Exactly. I was going to say the same thing. I think there’s a Bullseye one, too in the ‘50s. Yeah, there’s a few.

Puryear: Kirby influenced me in so many ways, including he did a thing that I love in another author, Charles Dickens. Where Charles Dickens will have these great names, Magwitch and Mr. Sowerberry, and Oliver Twist, those great names. And Kirby would do that over and over again with Armagetto, and even, the great one is Scott Free, Mister Miracle, Super Escape Artist. That’s a great Dickens-esk name. So, if you look at Concrete Park, we have Scare City, which is to me, channeling Kirby.

Jim: Clack-clack guns, the weapons?

Puryear: Oh, the guns, they’re also called like that, yes. Onomatopoeia, thank you.

Alex: In Kamandi there’s an insect with that name, right?

Puryear: Oh, click-click.

Jim: Yeah.

Puryear: It’s a cricket.

Jim: But clack-clack in the sound effects.

Puryear: Yes.

Jim: It’s so Kirby.

Puryear: Yes, and I’ll tell the world. I mean, when I came up with the name Scare City, for a minute, I went, “Thank you, Jack.” To me that’s kind of a Kirby-esk beat.

Alex: Yeah. That’s like a city on Apocalypse or something.

Puryear: Yes, Apocalypse. Armagetto. Scott Free, what a great name. Kamandi is a hysterical name.

Jim: For me, reading that, I thought it was like, you know how Kirby took over The Losers at DC, I felt like Kirby had been hired to redo 100 Bullets. That’s what your book was, to some degree.

Puryear: There is a strong, strong Kirby influence. As a kid, he opened up my imagination. He did that thing writers were supposed to do, it’s to make you want to be a writer. You know how the Beatles made more people want to join bands and be in bands. And similarly, for the punk movement. In 1976, ’77, The Ramones tour England, suddenly every kid in England has got a punk band. That’s Kirby. It’s like he makes you want to have a comic book.

Jim: We were interviewing Gary Groth, and he talked about the influence of Woodward and Bernstein sending everybody, of his era, to journalism school.

Puryear: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Jim: Which is what I majored in, for that exact reason.

Puryear: Oh really, how about that. That was a myth for our time, wasn’t it? In the ‘70s.

[chuckles]

Jim: Sadly.

[00:20:00]

Puryear: That was a real beautiful myth.

Jim: All right, I only got like five minutes to get us through your advertising career. So, you go to Brown as an art major?

Puryear: Yes,

Jim: But at this point, not to do comics, obviously.

Puryear: No, no. I’m the world’s biggest goof off. I kind of goofed off at Brown too. But the Brown Art Department is built on the site of H. P. Lovecraft’s old house.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Puryear: I always like that you know.

[chuckle]

Alex: You’re channeling Kirby energy and that’s a metaphysical other worldly, Lovecraft-y and things too, every now and then.

Puryear: In a different world, that perfect son of Lovecraft and Kirby is Mike Mignola.

Alex: [chuckle] There you go. That’s true.

Puryear: Look at his work… Yes. I went Brown, became a chef there. That’s where I got into the chef-ing thing. I paid my way through school by working in restaurants, and afterwards…

Jim: You got suspended a few times too, right?

Puryear: Kicked out of Brown five times, I still don’t have a college degree after four complete years of Brown. I’m a high school graduate, but I was doing a political organizing in everything that there was, I was against it. There was apartheid, there was nuclear power, there was everything. I was that guy. So, I was cooking in restaurants, and going all over New England, speaking…

Alex: What year is this part?

Puryear: This is ’78 through ’83.

Jim: So, why cooking? How did that come about?

Puryear: We had cooks in the family. Again, light skinned black people who got to work in the house. My father’s people, his mother and all his aunts, they were those big fat black women who’d come to Thanksgiving with the two Turkey in the van… It was those women. And I learned to cook from them. And I cooked at Brown in the dining hall. It was awful. You would see a beautiful meal would come by, I’m doing the dishes, a beautiful plate… Somebody just stubbed out a cigarette in it because the privilege of Ivy League kids… But I learned to cook. And so, I ended up, till about 1983 being the chef at this gourmet seafood joint.

A lot of mob guys came in. That influenced my later career. I wrote Eraser because I knew these mob guys. So, I was a cook. And then I went to New York City, and summer of ’83, a very important summer because I was also working as a DJ in clubs. Suddenly, music video came in, and 1983 was the summer of Michael Jackson’s Beat It. Huge video. Billie Jean. Kids would pay to come to venues I would host, just to see the videos. Because a lot of kids, especially black kids, in Providence, Rhode Island, didn’t have MTV yet. But they’d come and pay me a couple of bucks at the door to go see these videos and dance to Michael Jackson.

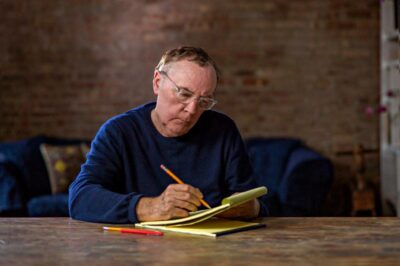

Then I got the idea, “Oh man, I’d love to be a music video director. So, I went to New York City in the summer of ’83. And I’d heard that all these guys directing these videos had worked in advertising. So, that sort of got in my head, so I applied for work at some of these ad agencies. And the place where I got the most traction was a place called J. Walter Thompson. Big ad agency, they had the Marines and Ford Motors and Kodak, all these big brands. And the creative director there was Jim Patterson. He’s now James Patterson, this big novelist. The world’s bestselling author.

Jim: So, he didn’t seek you out, some reports have that he sought your food designs…

Puryear: No, no, no.

Jim: You went and applied for the job.

Puryear: Yeah, and I didn’t know what I was doing, but I had some storyboards I had drawn, thinking that would be the thing. And they kept passing me up the line, the different art directors at Thompson said, “Oh, you ought to talk to Jim”, and I’m like, “Who the fuck is Jim?” I’m being fobbed off to some Jim guy.

[chuckle]

Jim turned out to be James Patterson, and he was the creative director. And he had written the jingle Aren’t You Hungry for Burger King Now. He was the guy who realized that everybody watching TV late night, they were stoned, they were hungry. So, he would have Elisabeth Shue, the Burger King girl. She became later, the movie star, Elisabeth Shue. But she would be like, they’d show big food, like this… and then she’d go, “Come on, we gotcha. Didn’t we get you’re hungry?… You know you’re hungry.”

Jim: So, this was after Burger King went through its flame broiled period, and then hired two different ad agencies, and there was a real attempt to up their awareness? Was this a new ad campaign that you were working on?

Puryear: No, I mean this was… Let’s see… ’83, ’84, ’85, ‘86 when I was working on, Thompson had the Burger King account and had successfully positioned themselves as tasting better than McDonald’s.

Jim: Right, the burger wars.

Puryear: The burger wars. That was exactly the time, and Patterson hired me among other things because he liked the fact, I had no advertising background. They had a lot of people working there who had gone to school at the University of Texas and all these other schools that have advertising majors. He thought it was cool to have an amateur, and also somebody who’d been a chef. He said, “Just make the food look pretty, man. Come on”, because the food didn’t look as pretty as it should.

Alex: So, because of you being a chef, and your sense of food design is what caught his eye then.

Puryear: Yes, and also, I could express myself visually. I could draw story boards, and I don’t know, he was that kind guy who would hire a weirdo hire…

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: Almost to pissed his other creatives off, to be like, “Look I’m hiring guys off the street who’re chefs, so you guys better step up your game.” I was partly a strategic hire too. I don’t know what I was doing.

Jim: Did you do Goodyear as well?

Puryear: Yes, I worked on Goodyear for a while but Goodyear was the most corporate client we had. I did print ads for Goodyear. Man, they were so conservative. I mean, Burger King was conservative.

Advertisement

I’ll tell you a quick story. We would go flying down to meet the franchisee of Burger King. Their headquarters were in Miami, and you meet these guys, they were all from the Midwest with plaid pants and white belts, and white shoes. Those were the clients. They would look at our work for Burger King and say, “You know boys, it’s creative… It’s a little too creative. So, can you scale it back by about 20%?”

[00:25:06]

[chuckle]

That was the brief, 20% less creative. Yes, sir. That was advertising.

Jim: I’m going to turn you over to Alex. You’re there, we know what you’re doing, but then you have some kind of eye injury, or something, an accident…

Puryear: Oh my god!

Alex: So, you’re working on advertising, design, and then there was a temporary blinding. What exactly happened?

Puryear: If you can imagine this. I mean, I was being paid nothing too. They used to say advertising is a great job, if your parents can afford to send you. I was making $16,000 a year, but Patterson gave me the assignment of making the corporate film every year. There’s like a corporate Christmas film. So, you can imagine there were 2,000 people working there in this big Madison Avenue headquarters. It was on Lexington but it was very much in Madison Avenue. And so, I made the Christmas film.

One day, I’m filming the Christmas film with a Super 8 camera because we did different media, Super 8 video. And I scratched my eye with the rubber eyepiece of the camera.

Alex: Okay, like a corneal abrasion or a corneal ulcer, something like that.

Puryear: Scratched my cornea, simple as that. Scratched my cornea, and got a bad infection. The infection went my other eye as well…

Alex: Oh, no.

Puryear: Because tear ducts communicate.

Alex: Were you wearing contact lenses?

Puryear: No. I just scraped my cornea, and kept on working. But by that night, I was like, “Urgh…” In incredible pain. It’s very painful. I went to the Emergency Room, I had this high fever, blah, blah, blah.

Alex: Oh, really.

Puryear: They had to pack my body in ice and all this dramatic shit. The fever came down, blah, blah, blah. I had bandages on both my eyes. When I went to the eye doctor afterwards…I had an old German Jewish eye doctor, named Dr. Frankfurt, who been in the camps. He had a big purple tattoo on his arm, Dr. Frankfurt. So, he didn’t give you any bullshit. He looked at my eyes and he was like, “I’m very sorry, you’ll never see again.” “What?” He said, “I’m sorry you’ll never see it again.”

Alex: So, this was like there’s a lot of corneal scarring and things.

Puryear: Yes, in both eyes, it was black. Just fucking black. Forgive my language, that’s how I talk, I’m from New York.

Jim: It’s okay.

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: Yeah, so it was very bad, and very scary. But over the course of a year, he sent me to see these specialists… They freeze the surface of your cornea, and they scrape them with a scalpel, literally, like the torture of the damned. It was crazy. But over the course of the year, I got my eyesight back.

Alex: Yeah, that’s good. They scrape the scar tissue off, it kind of heals. They’d give you some drops and things. It’s a long-term process.

Puryear: Yes, like plastic surgery. Let’s diminish that scar. You got it exactly right. And it was weird because I’m tapping my way through midtown Manhattan, on Lexington Avenue with my little cane and Patterson was like, “You know I can’t fire you. That would really be against the law because you’re handicapped. I can’t fire you. But now, you can’t be an art director anymore, so you got to write the commercials.”

So, he had me writing commercials. And he was really a writing mentor. He’s a very mean… You know I love him. But he’s a mean, unforgiving son of a bitch too.

Alex: Was he very East Coast in his mentality?

Puryear: I don’t know… East Coast. I mean he was very… How do I say this?… I’ve met people who are smarter than Jim Patterson. But I never met anybody who used more of his intellectual horsepower for his work. His mind was very organized like that. Everything was on yellow legal pads. This day, he has 15 books being written by different ghost writers and he’s got them all on legal pads, and he’s just organized, and focused, and hard working. And he was very unforgiving of people who didn’t work hard like that. So, his work ethic was like … Like this.

Alex: I see.

Puryear: And he scared us all to death. We were all scared to disappoint him. So, that made me a writer. And he would take a blue pencil through your shit and just be like, “No. you said that already. It’s redundant. You don’t have to say that yah, yah, yah, yah.” He’s a great editor.

Alex: But he trained you at writing. Is that what you were saying?

Puryear: Yes, very much, very much. and so, by ‘87, I was trying to write my first screen plays, and they were bad. I remember, once going to Patterson asking him to invest, because ‘87 was like the summer of, She’s Gotta Have It. I want to make a movie like that too. I said, I could do that. I need investors.

Alex: So, basic writing and directing, all that was going on your mind in the late ‘80s.

Puryear: Yes, sir.

Alex: Were you also directing the music videos around this timer, or was that before that?

Puryear: A couple of years later, probably about ’88, ’89, ’90.

Alex: Oh, it was later. Okay, cool.

Puryear: But by ’87, I’m thinking I want to be Spike Lee. And I wrote a script, I went to Patterson, asked him to invest and he said, “It’s just not funny.” I was just like, “Ouch, that’s so…??? And he said, “And from my nickel, which by the way you’re not getting…”

[chuckles]

“You need to rewrite this whole thing.” That’s how he would speak to you. He was so tough, but without a tough Obi-Wan Kenobi like that or whatever, without a tough mentor, I wouldn’t be the writer I am. I think I have a decent work ethic now, but it’s thanks to him.

Alex: I see. That’s great. So, you would say you more creative rather than rigid and disciplined, but then he kind of put some of that discipline in to you.

Puryear: Oh my God. creative work means nothing if you don’t organize your shit, and make sure… It’s great to have something creative but we need to fund it. And 9:30 on Monday won’t do; the meeting’s at 9:00, period. It’s the stuff like that. So, yes, we worked weekends. We all wanted to please him, and it made me a good writer, I think. I mean, it made me at least, a hard-working writer.

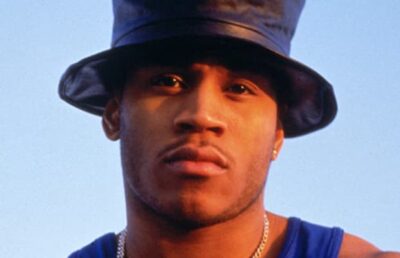

Alex: Yeah, that’s awesome, that work ethic, I think is really important. Tell us about the aspirations to become the next Spike Lee, and then start to direct the music videos, because they’re music videos LL Cool J, K-Solo, EPMD.

[00:30:07]

Puryear: That’s correct.

Alex: Tell us about that.

Puryear: Because I could draw storyboards, at that time music videos were blowing up. I knew a couple of people so I’d go… You know that song Rhinestone Cowboy, where you’re walking down the streets of Broadway, that was me. I swore I was never going to be like my father like a salesman, but here I was on Broadway with my little chase of samples, in this case, storyboards. [overlap talk]

Alex: [chuckle] Like an encyclopedia salesman.

Puryear: Yes! Like Willy fucking Loman. And I’m knocking on the door of like, Russell Simmons Def Jam, and other record labels that were all on Broadway, or either on Time Square, or on Lower Broadway, down in the village.

I’ve never got a job from Russell Simmons. To this day I hold a grudge. But I started getting jobs from these other small hip hop labels. There was a label up in Broadway called Sleeping Bag Records. I did their corporate film, and then I did a video for them with Biz Markie, KRS-One, they worked for Sleeping Bag. And then finally, I got to do EPD who was their big artist. You know EPMD? Did that video, and that led to doing K-Solo. The EPMD video had LL Cool J and it’s how I got to work on the LL Cool J project.

So suddenly, I was working, but the budgets for these were microscopic, and if you went over budget, that came out of your pocket. So, I think I lost money on all the videos I ever did but…

Alex: Oh man, okay, but definitely probably learning experience. I’m sure.

Puryear: Great learning experience, great to be in the editorial, when you’re putting it together and you realize, “Oh God, I didn’t shoot my coverage. What am I going to do?” The video I did for EPMD was called You Had Too Much to Drink. And it’s a simple thing about a guy getting drunk. The chorus is, “You over did it, homes. You had too much to drink.” I’m sitting in the editorial bay, and the editor is saying to me, “You didn’t shoot it, homes. We don’t have enough to cut.” So, those were learning experiences.

[chuckle]

Alex: How was LL Cool J and Biz Markie in them, to work with in the late ‘80s.

Puryear: Oh my… I mean EPMD, one guy was hardcore business, Parrish Smith. He was hardcore. His partner Erick Sermon. Erick Sermon had kind of mush mouth, he talked like this, “Waz up, how yah doin… Wuzza dancers at. I wanna see the dancers. Wuz the dancers?… “ You know, like that. But they were business like.

LL Cool J, lovely guy, but he would come on set and get everybody high, 11:00am the set is working really great. We’re filming, everything’s great. Noon, everybody’s having lunch, LL Cool J brings all this weed. By one o’clock, everybody’s like, “Let’s shoot it.” They’re like null and void.

Alex: [chuckle] That’s amazing.

Puryear: I like LL Cool J, he’s from Queens, like me. But LL Cool J brought the buzz, and everybody got high and then everybody was useless.

Alex: I don’t know about you ladies and gentlemen, but I’m having a great time. Jack Kirby, LL Cool J, all in one thing. This is a lot of fun. I’m telling you.

Puryear: I’ve lived a long time, and I’ve had this weird colorful life. That’s true. I’m very lucky.

Alex: [chuckle] So, now this is kind of a sec order to 1990, but Jim and I were discussing your 1995 Variety article, Yesterday, but there is a sentence, “Can a former chef and Madison Avenue man”, that’s the advertising reference, “A self-proclaimed dilatant who paints, writes, cooks, composes, and computes but never learned how to drive, find happiness in Hollywood?” Tell us about five years earlier, in 1990, you were selected for the inaugural class of the Walt Disney Company’s Writer Program. There’s a lot of interesting writers that came out of that as well; writers from Mad Men, Once Upon a Time, Psych, Chicago Fire. So, tell us about getting accepted into that. Walk us through that process.

Puryear: Sure. The picture I wrote, that wasn’t funny, that Jim Patterson said, I wasn’t getting his dime or his nickel, a black producer in New York City had read it, and she recommended me to the Disney Program. And it was 1990, they were looking for minority writers. And again, I mean here’s a whole question about race, a social construct. The Disney Program at the time was called the Disney Minority Writers Fellowship. It was that because Jeffrey Katzenberg really was stung by criticism. He was running the studio. He was stung by criticism from the NAACP that all of Hollywood studios had a horrible record behind the camera, in terms of hiring minorities. But Disney was the most egregious offender of all.

So, he created this program, very proactive. Let’s go get a bunch of black writers. Let’s train them up, minority writers of all kinds and all stripes. Let’s train them and really show the world that we’re committed.

Alex: Wow. That’s cool.

Puryear: So, they did that program, they had an agreement with the Writers Guild, paradoxically, that they couldn’t pay us what a normal guild writer would be getting then… Back then the Writers Guild minimum was like 50grand. They paid us 30grand or like three fifths of what a guild writer would normally get… [overlap talk]

[chuckles]

Alex: Really?… [overlap talk] What the heck?

Puryear: Right there. But for $30,000 I was very happy to take it. I was broke. I was missing teeth. In New York City, things were bad. I was starving. So, I came out to California, only to discover that the first class of the Disney Minority Writers’ Program looked a lot like me. In other words, it was a bunch of very, very light skinned, could pass for white almost, black writers and minority writers. There was a Latina writer, her name was Natalie Chaidez, whom I worked for just last year on Queen of South. But Natalie Chaidez is a blue-eyed blond, very Anglo-looking Latina. And there were several of them, Maya Forbes who could pass for white, looks like me, she ended up writing Monsters, Inc and all these pictures.

[00:35:03]

I sort of fit in, and I was one of those acceptable Hollywood black people for Disney… That got me started though. Learned a lot there.

Alex: So, there was like, “I’m glad to be here”, but then there’s also little like, “That’s a little suspicious that it’s like the light skin.”

Puryear: True. Yeah.

Alex: But I mean life’s double-edged, I guess, sometimes.

Puryear: Life is like that. And at the time, I was like, “Well I’ll take it.” They promised to get us into the guild. They promised to introduce us to a lot of people; that didn’t really happen but they did do things. Like they brought in Robert McKee, the guy who wrote that book Story for an intensive three-day thing. You’re locked in a room, for three days with Robert McKee, who was like an old alkie who like was late for his first drink.

[chuckles]

He was sort of like a mean guy… I hate to say this, I’m probably… What’s the word, slurring him or libeling him, but he’s a mean guy but his teaching was great. I mean, Robert McKee knows what he’s talking about for sure. Thanks to him I wrote pictures that got me some success. So, there you go.

Alex: So, now you were writing scripts for Disney.

Puryear: Yes, sir.

Alex: And how long was the program exactly?

Puryear: It was a year for each person, but they re-up me for a second year. So, we’re talking ’91, ‘92. It was a time when it was like the beginning of the downslide of Eddie Murphy’s career, but Eddie Murphy still the biggest black thing in Hollywood.

So, a typical pitch to me from a Disney executive would be, fill in the blank for the coded racism of all this… “Okay, it’s New York City, Leroy is a fast talking, jive talking New York street guy, okay. And he stumbles on to some gold.” I’m sitting there going, “No, I’m not writing this picture. This picture is already racist. Fuck you.” [chuckle] so but that’s the kind of pictures that they would pitch to us.

Literally, I ended up writing a picture of for Disney called Talk Fast which was about the black radio business. And I still ended up writing per their guidelines, a picture about a fast-talking young black guy who breaks into the black radio business.

Alex: So basically, they’re plotting ideas to you and then you write a script?

Puryear: They were pitching things to us; we also could pitch things to them. I come and go, “Okay, I’ve got script about the 1931 squadron of black women aviators in Alabama, who later went on to be in the Women’s Air Corps.” And they’d be like, “No.” Okay, so then we pitch them something else.

Alex: Fascinating. I also find that the terminology is interesting, because in comic world, that’s like they plot it. But in movie world, it’s called a pitch.

Puryear: Uh-hmm. And it’s a pitch because it may not go anywhere. It’s like, “Picture this, New York City, 1995…” It’s a pitch.

Alex: [chuckle] I love that.

Puryear: And then you learn the skill, this served me good in stints later on, of going in a room totally like a salesman again, and say, “Okay,” it’s like the opening scene of The Player, right? The guy comes in, “The scene is devastating. Rain coming down, umbrellas lit from below with the candles…” You pitch it. That’s a pitch.

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: So, we go on pitching back and forth at Disney, but they have a very narrow bandwidth about the kind of pictures they wanted their black writers to write.

Alex: It’s funny you’re bringing back all these emotions and memories, because I was a film minor in college, back in the ‘90s. So, it’s funny, you’re bringing back these feelings that I’ve forgotten about, actually.

So, now when you were writing scripts for that… So, Disney would retain ownership of those scripts?

Puryear: That’s correct.

Alex: Okay. Were there scripts that you’d had written, that’s part of that program that people may have seen later, that we’re produced?

Puryear: No, I don’t think any of us ever had a produced picture out of that. There were 30 writers in my class in the first Disney program. And partly, it’s because… I mean, it was window dressing. It was like, “Look NAACP, look all these negros we hired. How great we are.” There was that aspect to it too, but I think, just none of our pictures broke out. They weren’t that good. I don’t know… But no, the Disney machine kept on going without us.

Advertisement

Alex: I see what you’re saying. Were they as hard on you as Patterson was?

Puryear: No. Not at all. They were, not to criticize, but they were sort of sloppy, disorganized. They have this giant headquarter on their lot. They built this new building, that everybody called “Mouschwitz” because it looked like a giant… Like a thing in the cemetery where you put the coffins above ground, a mausoleum.

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: And they called it the “Mouseleum” too… And they had thousands of executives, spending billions of dollars, making hit or miss pictures. Although, coming out of that Disney program. I met somebody really great. I met Bonnie Bruckheimer, who I believe was Jerry Bruckheimer’s wife at some point, whatever. But she was business partners with Bette Midler, who was on the lot. And Bette Midler who, when Katzenberg and {Michael) Eisner took over that studio, Bette Midler helped them with a series of really good successful middle-brow pictures. She really was big for a moment.

Then Disney moved on, and when I met Bette Midler, she was sitting there complaining, “I helped build this. The new iteration of this studio, and now, they won’t answer my phone calls.”

Alex: Wow. Okay. The rise and fall of Bette Midler, who would have thought.

Puryear: Yeah, really. And I wrote a picture for her, that didn’t go anywhere. I guess, it didn’t make it in the end. But she was a great boss to work for, very funny. You know how there’s different kinds of, in baseball there’s both speed and quickness? Speed is how fast the guy runs the base pads but quickness is how fast they’re off the base. Bette Midler had quickness. Bette Midler was like this… and was sharp with the joke.

So, she was a great boss to work for. But our picture didn’t get made.

Alex Huh.

[00:40:00]

Jim: This was all Touchstone brand, right?

Puryear: Back then they also had a second label called Hollywood Pictures and that’s who I worked under. But yes, Bette Midler was affiliated with Touchstone, yes, that’s correct. Hollywood Pictures is no more.

Alex: Now, when did you start writing Eraser? When was that? And that’s the Arnold Schwarzenegger film, huge blockbuster. Vanessa Williams, someone I had a crush on in high school. When did you start writing that story? What year do you think?

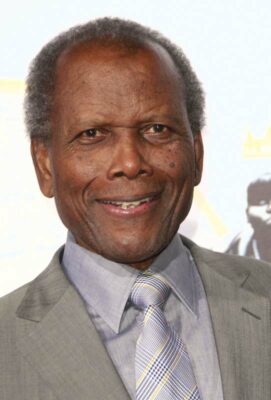

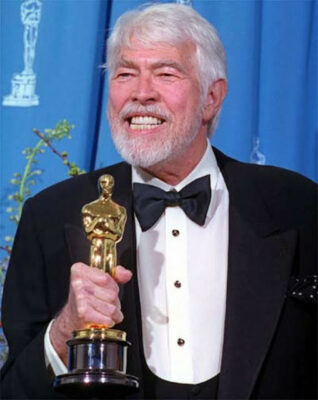

Puryear: Okay. Well, by ‘92 I’d written a picture for Bette Midler that didn’t go anywhere. I got hired by Sidney Poitier at Columbia to write a detective thriller for him. It was the last picture… He had to deal with… You heard of vanity deals, right?

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: Where a lot of stars… Back when Patrick Swayze had a vanity deal at some studio. Meaning they give him a secretary, they give him some offices, they pay them his overhead and they develop pictures which either do or don’t get made. A lot of those vanity deals, the pictures didn’t get made.

Well, Sidney have made a lot of great pictures for what was then Columbia Pictures that turned into Sony. So, they had Sidney Poitier on this deal, and I wrote a picture for him. It didn’t get made and they sort of gave him the kiss off, they named a building after him and then they ended his deal.

Alex: Oh wow. Was he a nice fellow?

Puryear: Very strict. I’d go to his house, and there would be the Oscar, that he got for Lilies of the Field. He should’ve have gotten it for Heat of the Night, but he didn’t. ’66, he got the Oscar. The Oscar was from 1966, and so many people had held it, that the gold rubbed off.

Alex: Oh, no.

Puryear: And you could see the lead. He used to say things to me like this, he would say… Actually, he didn’t say… He had a man to do his yelling for him. Sidney would get mad at me and stand up and leave the room. He wouldn’t debase himself to do the yelling, but he had a guy… He was from the Bahamas, and he had this other guy from the Bahamas who would say, “You know, Sidney is very, very angry with you. You’re such an impudent young man. You say everything that’s on your mind. Look at Sidney, he’s very angry. I don’t know if he’s going to come back.”

Then Sidney would always come back, and Sidney, his way of making peace with me, because he was so furious, he’d go, “You want a sandwich, kid?” I’ll be like, “Yeah.” So, Sidney Poitier would make me like a tuna fish sandwich.

Jim: That’s amazing. It’s like the Key & Peele routine with Obama, where he was half the angry guy.

Puryear: Yeah, yeah. Sidney had this guy named Cedric who was another Bahamian… And you know, by the way, here’s the root of it. Though Sidney grew up dirt poor in Miami, Florida. He was from Cat Island in the Bahamas. Grew up real poor, couldn’t even read blah blah blah. Still from that British Bahamian upbringing, there’s certain ways you speak to your social betters and your social inferiors.

Alex: Yeah, yeah.

Puryear: So, Sidney spoke to me like I was the pool boy, a little bit. At the same time, I’m an American, no man is my better. So even though he was Sidney Poitier, and I’m very intimidated by him, he’s To Sir With Love. I mean, he’s Sidney Poitier. I’m going to speak my mind and say, “Sidney, I don’t think that’s a great idea.” And Sidney would turn purple and stand up, and leave the room… Because the pool boy had spoken out of turn.

[chuckles]

Alex: Ha! Amazing.

Puryear: So, I seen him around. I haven’t seen him in years, but I mean I would see around after that and he was always very kind to me. He’s a great guy. He’s a gentleman but he was mad at the way I spoke.

Alex: Yeah, he had a British sense of social structure, it sounds.

Puryear: Yes, very much. So, by ’94, I had agents, they were awful. They were gonif. You guys speak Yiddish? A gonif, like a thief. These guys will steal your front teeth. They were my agents. That’s the agent I got. And I was writing all these big science fiction stuff, and they were like, “Why don’t you write something simple, like boy meets girl. Something we could sell.”

I thought, I can’t write boy meets girl. I don’t know how to do that. But I could write boy saves girl, that I could get my head around something simple. And I’ve been reading a lot of John le Carré. I love John le Carré’s books. He’s this amazing writer. He has good secrets that he holds back and deploys like little atom bombs. I thought that’s great.

I had known all these mob guys up in Providence, Rhode Island, and they always told me as like a joke that the Witness Protection Program was bullshit. The Witness Protection Program was Swiss cheese. Those marshals make $40,000 a year or whatever they make; they make nothing. You just slip a guy like that a fazool, and he’ll tell you where the witness is.

Alex: Ha! For a fazool, no less.

Puryear: For a fazool, yeah.

[chuckle]

So, I thought, okay, the Witness Protection Program is no good, but there should be like this super marshal, who will save you, no matter what. By the way, also this is partly coming from Ian Fleming. Ian Fleming’s conception of James Bond, he said was a guy who will break your neck, a killer. But he’s also Saint George of England. He’s also that guy.

I wanted to make a hero like that, so I created the Eraser. The guy that will hide you, and save you in the Witness Protection Program, no matter what. He’ll break a neck, but he’s Saint George of England. I wrote that in ’94. ’94 was the summer of Speed, when Speed had come out and renewed the action picture

Alex: True.

Puryear: And I knew a woman who knew the guy who managed Keanu Reeves, and she read Eraser. She thought it was good… It took me a year to write it. I couldn’t have written it without the lessons of Robert McKee, and I thought it was a tight, good little John le Carré influenced thing with good secrets.

Alex: And you didn’t have Arnold in mind, when you wrote it.

Puryear: Not at all.

Alex: I mean you’ve seen the movie Commando with Rae Dawn Chong, and then The Bodyguard with Whitney Houston. Was any of these in your mind? Or was it more in the spy – federal genre?

[00:45:09]

Puryear: It was dark and little… To me. I thought of a guy, the Eraser, as a guy you wouldn’t notice sitting in an airport. Whereas you would notice Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Alex: Yes. So, almost, it’s a little off script, a little bit there.

Puryear: Yeah, yeah, I mean, we used to say, who’s my favorite producer? The producer who buys my movie. Who’s my favorite movie star? The movie star that gets my movie made. So, if they’d have put Jackie Chan in the movie, I would’ve have been happy if it got made.

Alex: [chuckle] That’s true too. Yeah… Just get the movie done, yeah.

Puryear: Here’s a true story, if you got time.

Alex: Yeah, of course.

Puryear: About the tale of Eraser.

Alex: We’re having a great time. Yeah. Keep talking.

Puryear: I was broke, living in Los Angeles, behind on my rent, living with a roommate, we had lived through the Northridge earthquake, but I took a year to write Eraser.

I knew a woman who knew the manager for Keanu Reeves. She read it. She liked it. She took it to this young manager at that firm, and he was like a reptile. His name was Daniel. And he called me T. He was like, “T, this script is very commercial. I can sell this tomorrow. It’s very commercial. Let me sell it, buddy. I’ll sell it for you.”

[chuckle]

I’m like, “Yeah, yeah. Please.”

So, the next day, he put it out, in like this bid situation to a couple of studios. He had leaked it out, made a competitive bid, and by the end of the day it sold to Warner Bros, in a competitive situation with Fox. And the weird thing was, it was the day of the OJ Simpson low speed chase.

Alex: Okay. White Bronco Day.

Puryear: White Bronco, at five o’clock, there’s two competing bids for my script and we’re sweating it up… 5:05, the low speed chase starts. It’s a Friday, everyone’s glued to the TV, including us. Warner Bros stops. Fox stops. Everyone’s watching OJ. And that took two hours, going up highway. I’m like, “You’re going to screw the sale of my script! I need money, please.” Finally, OJ drove home, the cops arrested him… 7:30, Warner’s makes the final offer. They got the script. I sold the script on that day.

Alex: Now, are you able to say for how much they sold this script for?

Puryear: Yeah, yeah. It’s sold for a quarter of a million dollars.

Alex: Nice. That’s awesome.

Puryear: Which, I mean, I was going from zero, from less than zero… I remember at 7:30 that night, business affairs of Warner Bros had made their final offer, $245,000. And the manager, this new manager I just met, this reptile, he goes, “You know my client doesn’t want to tell his parents $245,000. He wants to say a quarter million dollars… Will you just kick in the extra 5,000 bucks, and we can all go home?”

[chuckles]

And so, they did. And that was how the deal was made. I was so afraid. I was so afraid that this guy would screw it up. But that’s how that deal was made. And I went from zero to a check for quarter million dollars. It blew my mind.

Alex: Yeah, the power of Hollywood. That’s awesome.

Puryear: Yeah. And then I hit the lottery a second time when Warner Bros slipped it to Arnold Schwarzenegger. Lorenzo di Bonaventura was the head guy there at Warner Bros, and he gave it to Arnold on a ski lift that winter. Arnold read it, and liked it. And Warner’s had never made a picture with Arnold. He’d made pictures everywhere else in town, so they were eager to get him. And he signed on.

He called me up one night, Arnold Schwarzenegger… I live right up the block from his office. I lived in Venice and right down the bottom of the block was his restaurant. And Arnold called me up one night, and he goes, “Hello, Tony, this is Arnold. How are you?”

[chuckles]

He says, “So, I read the script today. It’s very good. What do I wear?”

This a true story. And I’m thinking like a writer, I go, “Well, metaphorically, he’s a loner. He wears a veil of pain. He wears black a lot.” He said, “No, no, what do I wear? Because you know in Commando, I’m having the short haircut. And then in The Terminator I’m having the leather jacket. So, what do I wear?”

And I said, “Well, you wear a bunch of cool shit, man. You’re a marshal, you got to let your strap, you got a lot of guns.” “Thank you. Thank you. Okay.”

Alex: Yeah, guns I understand that. Yeah.

Puryear: And he goes, “Also, what is my gun?” I’m like, “Really? What do mean?” He said, “Well every time I’m working also with Jim Cameron, he’s giving me what is the latest gun.” So, I just bullshitted right there and then. “Well, maybe it’s a railgun where there it’s firing fucking ceramic projectile at a quarter of a million miles an hour.

[laughter]

“Thank you. Thank you.” So, he hung up. And then the next day, he signed on.

Alex: That’s great. The railgun. It gets it every time, right?

Jim: This makes such sense, because he was just coming off of True Lies.

Puryear: Yeah.

Jim: So, the guns and the wardrobe would make total sense…

Puryear: Yeah.

Jim: That he invested in that.

Puryear: Yeah, and he wasn’t thinking in metaphors. He wanted to know what he’s supposed to wear.

Alex: Yeah, very concrete question… So, were you excited to hear that he was part of the project? Or were you like, “I was thinking of a different guy? Was it more like the commercial aspect of you, was excited, or was it the artistic aspect of you was disappointed?

Puryear: I was happy to have a job. Him planning on to do the movie, meant the movie got the proverbial green light. That triggered a production bonus for me which was the same as what they paid me to buy the script.

Alex: Nice.

Puryear: That stroke of a pen, suddenly, I doubled my money. I don’t mean to be a mercenary about this but… that’s how it happens.

Alex: Survival.

Puryear: And then immediately, a phase of my contract kicked in, where I wrote a rewrite. Then they hired a bunch of other writers do rewrites. They hired me back. I wrote 13 different drafts of that script.

[00:50:02]

Alex: Oh, okay. So, you were doing the rewrite to that.

Puryear: But so did 13 other writers.

Alex: Okay.

Puryear: When we went to the Writers Guild for arbitration, they got a big crate with 56 different draft of Eraser. This is all taking place in a year.

Alex: Wow.

Puryear: And Frank Darabont wrote on it. Chuck Russell, who no one liked… I would say this honestly. Chuck Russell, the director, he did a lot of rewrites trying to write everybody off the page. In the end, the Writers Guild awarded me and a guy named Walon Green, credit for the picture. Walon Green wrote The Wild Bunch. Great writer and a real gentleman; lovely guy. But there were 13 other writers too in addition to me. But I kept getting paid to rewrite it. I got a lot of money just rewriting that damn picture, over and over again.

Alex: It was feeding you for a while.

Advertisement

Puryear: Oh dude, the weird thing was, that help me get other jobs because, A) my name was in the paper, like you saw on Variety, “He sold the picture”… but B) the word got around, that at least I acted professionally when it came time to do the rewrites. And I didn’t hold a grudge that I kept getting fired off the picture… But that’s life… Another the guy comes in, then you replace him.

So suddenly, I started getting other work, and booking other work because I had a decent reputation.

Alex: Did you write Vanessa Williams’ character, originally, as an African American woman?

Puryear: No, that’s Arnold. You notice, he had Rae Dawn Chong. He’s had Maria Conchita Alonso.

Alex: Yes, so that was Arnold. That’s cool.

Jim: That’s interesting.

Puryear: Because he was looking for somebody age appropriate, but also, he knew that a lot of his audience was people of color. Arnold always thought that.

Alex: Wow, that’s awesome. I like Arnold, so that’s cool.

Puryear: One weekend, we were locked in a hotel doing these rewrites, and we were sweating, and we were eating pizza, and it was two days of awfulness. Then we had to drive up to Arnold’s house to pitch him the new rewrite. And we go up there, Arnold has just been in Vail, Colorado somewhere, skiing. He comes in looking like a god, looking like the sun is shining just for him.

Alex: [chuckle] Perfect. Perfection.

Puryear: Including Lorenzo di Bonaventura from the studio. We’re all sweaty, beard stubble, and I say, “So Arnold, I think in the end, the train runs the guys over.”

“That’s great. Thank you. Thank you very much.” That was it. He was cool like that. I mean he’s a big movie star. That’s that story.

Jim: Did you ever talk politics with him?

Puryear: No. Like a lot of self-made men, he had a very disdainful attitude about people maybe who weren’t as self-made as him. There aren’t that many, who are as self-made as Arnold. So, I thought he thought politicians were grubby and sort of beneath him.

He was a classic Leo. I mean I’ve met guys like him, alpha dogs, big dogs like Bill Clinton, another Leo like that, self-made man. Arnold had a really strong sense of himself that he knew what he was doing and other people could be kind of stupid about things. There was that. So, there’s two different sides, an admirable guy in many, many ways but also a guy who’s like, “Look at this guy, he’s stupid.”

Here’s a story…

Alex: We’re going to add, impersonator on your resume here, because you are funny.

Puryear: Oh my god… Here’s the story… Beginning of the picture, everything was great… “My good friend Chuck Russell is directing this picture. He’s my good friend. I’ve been skiing with Chuck Russell. He’s great. He did The Mask.”

Okay, that was at the beginning of the picture. By the end, everybody hated Chuck Russell. I went on the set one night, and everybody is like non-cooperating with him as hard as they can. The grips were pushing the dolly or pushing as slowly as they can. Everybody hated, hated, hated Chuck Russell. And I was with Arnold one time, when he called up Terry Semel, I think, the head of the studio, about replacing Chuck Russell. And he’s going, “I don’t know what you’re going to do with this director…”

So suddenly, Chuck Russell had gone from being, “My good friend Chuck Russell”, to being, “This director”. And Arnold is going, “You know I hear Joel Schumacher is available.” Right in the middle of the picture, in the middle of production. It was like that. So, Arnold could be disdainful and impatient, like a self-made man. That was him. I liked him.

Alex: Yeah, kind of an artist in some ways, and he’s the muscle guy, Mister Universe, right? And there’s maybe a little bit of an aspect of a Henry Ford type of personality maybe in there.

Puryear: Self-made… And he partly won, if you’ve seen that movie Pumping Iron, he partly won by mind fucking all the other competitors.

Alex: That’s right.

Puryear: Lou Ferrigno couldn’t take it. He’s like, “Look at you Lou, you’re not in shape. I’m in shape. Why are you not in shape Lou?”

Alex: [chuckle] Yeah, I…

Puryear: And he kind of mind fucked him right out of the competition.

Alex: Yeah.

Puryear: That’s Arnold too, he can be mean.

Alex: Yeah, and kind of mischievous about it too, a little bit.

Puryear: Yeah, yeah, yeah. He lives in Columbus, Ohio, in front of their civic center. And there’s a giant steel sculpture of Arnold Schwarzenegger doing the pumping iron, posing… [overlap talk]

Alex: [chuckle] Perfection.

Puryear: That’s where he does his Arnold classic body building thing every year, in Columbus, Ohio, of all places.

Alex: Yeah. Of all places, but they love him there, go figure.

Puryear: Oh, his big. He’s big in Columbus.

Alex: I watched Eraser last night, just so you know.

Puryear: Oh my god.

Alex: But there’s a couple little points I wanted to go through which I found interesting. First, Alan Silvestri did the music to this and the Bodyguard. Did the producers kind of be like, “Okay, he did good music for them, let’s put them over here too.” Do you know about how he got involved in that?

Puryear: Alan Silvestri was good friends with Frank Darabont.

Alex: Okay, there you go.

Puryear: One of the writers brought on, and Frank Darabont was good friends with Chuck Russell. We all couldn’t understand why Frank and Chuck got along, because Chuck was not a nice human being. Frank Darabont is a true gentleman, a real good guy.

[00:55:00]

And so Silvestri was something they talked about together, and Frank Darabont had worked with Silvestri on other things, or just knew his work. They got Silvestri, they were very happy. And Frank Darabont was happy for his friend Silvestri to have the chance to write a big action score like this, with things blowing up. That’s how that happened, I think.

Alex: It’s not just Arnold, there’s some really notable actors in this. You got James Coburn. You’ve got James Caan. It’s cool to just see these people. These are classic people. These are people from the Bruce Lee era here, that are in this movie. Was that fun to see?

Puryear: Yes, and Caan and Coburn actually really go back, meaning like James Caan before The Godfather, he’s in the Howard Hawks picture. I can’t remember if it’s Rio Lobo or Rio Bravo with John Wayne.

Jim: It’s not Rio Bravo, it’s Rio Lobo.

Puryear: Okay. Thank you. [overlap talk]

Jim: Because it’s a James Caan thing, Mississippi.

Puryear: Mississippi. Thank you. So, James Caan is from back then, and of course, James Coburn from back in like Magnificent Seven. So, that was great. But of course, both of them were older too. So, Coburn, had nearly lost a couple of steps, that was interesting to see. And I’d really admire him very much. And then there was James Caan who was in that phase of his career where he’s playing everything… Like this…

[chuckle]

Kind of funny… “Hey, I don’t know… Bada-bing, bada-bing.”

Alex: Yeah. “Ay… Oh… Hey.”

Jim: But Coburn had slowed down by that point?

Puryear: I thought so.

Jim: That’s interesting because like years, years later he was in the Nick Nolte movie Affliction. He’s incredible in that movie.

Puryear: That’s right. That was great.

Jim: He’s great in that.

Puryear: Yeah, listen, when I say slowed down, I just mean, you meet your heroes, and some of them are exactly like you think they are. And then some of them are older, and they’re sitting in a chair, and they’re not moving that much, there’s that.

Alex: Right? There’s a bit of a mortality.

Jim: He wasn’t Magnificent anymore.

Puryear: Yeah. Magnificent… But then, the funny thing is I love James Caan, but I thought he was not scary.

Alex: Right, because him like fighting Arnold fisticuffs, but he’s very charismatic though.

Puryear: He’s charismatic but I had made the right… I had hoped for somebody more menacing.

For instance, this picture was produced by Arnold Holtz and Kopelson was just coming off of The Fugitive. Great picture, and Tommy Lee Jones has that great combination of intelligence and a kind of menace. That would’ve have been a great bad guy in Eraser. James Caan, I thought the minute he comes in, I thought, he’s kind of funny, He’s kind of likable… “Hey…” You know.

Alex: [chuckle] You’re great with these impersonations. I’m amazed.

Puryear: He had a certain rhythm going by then, that was not so scary.

Alex: Yeah, yeah. I see what you’re saying.

Jim: Although James Caan kicking the shit out of his brother in law, in Godfather…

Puryear: Oh, come on, James Caan back then was great.

Jim: Couldn’t be better.

Alex: That Rollerball… Remember Rollerball?

Puryear: Yeah. And he just great in Misery.

Alex: Oh yeah…

Puryear: He’s that middle-aged writer…

Alex: That’s right, oh my god.

Puryear: “Please, please, don’t cut my legs…”

Jim: Bottle Rocket also.

Puryear: That’s right.

Alex: Bottle Rocket, oh my god, yeah.

Jim: He’s great in Bottle Rocket.

Puryear: I liked him in Elf.

Jim: Oh yeah, me too.

Puryear: But, you know, I worked for Stan Lee for a while, and Stan Lee would never say a bad word about anybody. Stan Lee, the worst you’d ever get out of him was, “I didn’t care for it… I didn’t care for it.”

Alex: What year did you work for Stan Lee then?

Puryear: Oh god… Stan Lee, it’s like 15 years ago.

Alex: So, in like 2005 or so?

Puryear: Yeah.

Alex: What did you do for him?

Puryear: We were both clients at UTA, and I hated my agent, and Stan hated his agent. That’s the first thing Stan said to me. He’s like, “You with UTA?… I don’t care for them. I think I’m going to change.” But he had a project… This is a good story… And forgive me. This is what I do. I tell stories.

Alex: No. These are great stories.

Puryear: Stan had somehow been hooked up with Majel Barrett-Roddenberry, the widow of Gene Roddenberry, Nurse Chapel from Star Trek. And Majel Barrett-Roddenberry had this thing where she always was finding pieces of the true cross, you know what I’m saying? She would find a piece of writing that was presumably the last thing Gene Roddenberry ever wrote. Now, she did that a lot… [chuckle] So, I don’t know.

So, she had a piece that Gene Roddenberry had written, and she and Stan Lee were in business. And Stan was looking for a writer, so UTA sent me over, we got along real well. So, we worked for a year on this thing. It was called Galaxy’s End, it was called Stan Lee Presents Gene Roddenberry’s Galaxy’s End, created by Tony Puryear. It was a TV show, I get the created by, but they get the front credit.

So, we pitched this around, and it became obvious, back then, that every executive in town wanted to meet Stan Lee, and get their picture taken with Stan Lee, but nobody wanted be in business with him. Because he had bankruptcy, he had this guy who stole all his money.

Alex: Stan Lee Media, yeah.

Puryear: We worked together for a year. It was lovely. Lovely guy, and me as a partisan of Jack Kirby, in the whole Stan and Jack thing. I told him right up front, I said, “You know, I love Jack Kirby and I knew him as a kid, so in my mind, like you stole everything from Jack.” And people even warned me about working for Stan, like, “Stan has a way of getting the best out of you, and then he gets the credit.” That’s what they would say.

Alex: So, you told him this?

Puryear: I told him this in the nicest way I could.

Alex: What’d he say?

Advertisement

Puryear: “I know what you’re thinking. I know what you’re thinking. But this is a collaboration, Tony, you’re going to get a lot of credit.

Alex: Ha! Okay.

[01:00:00]

Puryear: He was lovely to me. Beautiful man.

Alex: So now, a couple other points of Eraser is the alligator scene. Did you write that scene, by the way?

Puryear: No.

Alex: That was part of the rewrite. The interesting thing was, that was like early CGI going on in that scene.

© 2020 Comic Book Historians