Comic Book Historians

As featured on LEGO.com, Marvel.com, Slugfest, NPR, Wall Street Journal and the Today Show, host & series producer Alex Grand, author of the best seller, Understanding Superhero Comic Books (with various co-hosts Bill Field, David Armstrong, N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., Jim Thompson) and guests engage in a Journalistic Comic Book Historical discussion between professionals, historians and scholars in determining what happened and when in comics, from strips and pulps to the platinum age comic book, through golden, silver, bronze and then toward modern

Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians.

Read Alex Grand's Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland & Company here at: https://a.co/d/2PlsODN

Series directed, produced & edited by Alex Grand

All episodes ©Comic Book Historians LLC.

Comic Book Historians

Professor William H. Foster III & African-Americans in Comics Part 1 by Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

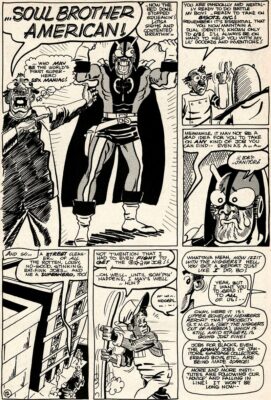

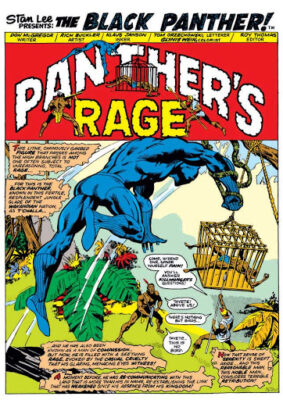

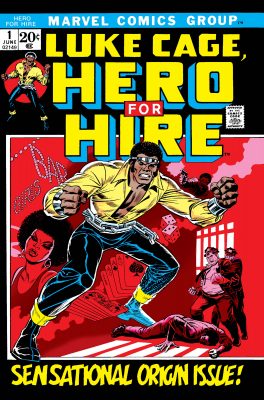

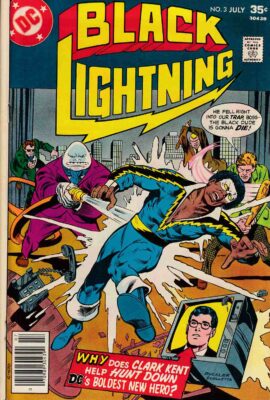

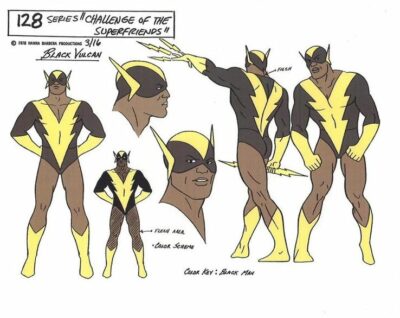

As featured in Roy Thomas’ Alter Ego Magazine, Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Professor William H. Foster III, published comic book historian, former Eisner judge and award-winning museum exhibit curator on the evolving roles of African Americans in Comics. William discusses his early forays into reading comics in the 1960s and 70s, then goes into a fascinating discussion of the portray and involvement of African American characters and creators in comics starting from the Yellow Kid, Krazy Kat, Ebony in Spirit, World's Finest, Sgt Fury, Fantastic Four's Black Panther, Luke Cage, Black Lightning, Black Vulcan, Fast Willie Jackson, Robert Crumb in Zap Comics, Storm of the X-Men, Sabre, Hypno Hustler, Milestone Comics, Trading Cards, Captain America, Thunder and ending into present day comic books. Originated, Edited & Produced by Alex Grand. Transcript available in Alter Ego 173.

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Music ©Lost European

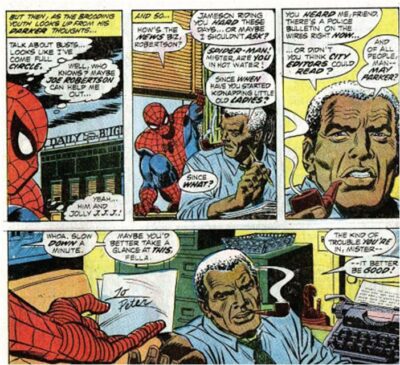

Professor Foster: My mind was blown, at the high school where Peter Parker went to, there were black students going, and he spoke to one of them. The guy said, “How’s it going today?” “Fine.” And that was enough for me. He can stop talking now. I like that idea that, it wasn’t like a special thing, “Oh, we’re going to a black school today.” He was part of an integrated school and you can’t imagine what that was like in the early 1960’s to see.

Alex: All right. Welcome again to the Comic Book Historian Podcast. Today, we have a very special guest, Professor William Foster III. A historian in comics that specializes African-American representation in comics. I’m Alex Grand, with my co-host Jim Thompson… Jim.

Jim: Hi, everybody.

Alex: Professor Foster, thanks so much for joining us today.

Professor Foster: Listen, it’s my absolute pleasure. Thank you, gentlemen, for extending the invitation.

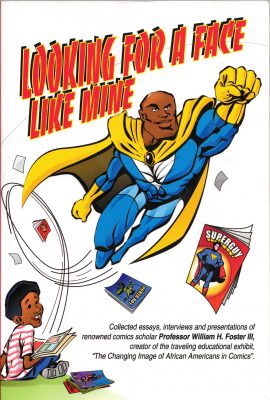

Alex: We’re going to start with kind of like your early involvement in comics. Jim is going to start off with that. Then we’re going to talk about your book, that I really enjoyed very much… We both enjoyed very much. Looking for a Face Like Mine, which is… Different articles of black representation in comics, which I found really moving and just really great history. Jim, go ahead and start with it.

Jim: Okay. So, Professor Foster, where are you from?

Professor Foster: Originally, Philadelphia.

Jim: Ah, and where did you move to.

Professor Foster: Oh, dude, how much time have you got?

[chuckles]

I went to school in Massachusetts, and then moved to Connecticut. I was working for Weekly Reader of all places. It doesn’t sound like a lot of fun but it was a lot of fun. And that’s where I am now, in Connecticut. Love it here.

Jim: Okay. All right, so no other parts of the country… Never lived in the South or anything like that?

Professor Foster: No. Detroit for a minute… And that was a blessing.

[chuckles]

I’m sorry. That’s wrong. But no, I got to tell you, I love New England, man. It really has an allure of its own

Jim: That’s nice. Yeah, I’m from Virginia, originally, so I’m a southerner. But…

Professor Foster: That’s where my dad’s from.

Jim: Oh, how about that. Where in Richmond?

Professor Foster: Richmond?...

[chuckles]

That’s the only family story I got.

[chuckles]

Jim: Okay… No, because which side of the river makes a great difference.

Professor Foster: [laughs] Doesn’t it always. Isn’t that true for every city.

Alex: I lived in Detroit for a year, but I was in Boston for a year, and you’re right. There is something about that New England vibe. I do love it too. It’s multicultural, it’s really interesting.

Professor Foster: I’m telling you, and it’s part of that New England… That northeastern brain trust that goes on in our country. I love that.

Jim: So, let’s talk about your entry to comics. When did you start reading? What books or lines were you interested in? That kind of information.

Professor Foster: No problem at all. I started when I was about 11, reading comics. But I was a voracious reader. I read… You know that old insult that you’d give somebody, “Eh, go read the encyclopedia.” That was me. I was the, “Eh, read me the encyclopedia” I couldn’t get enough.

And comic books were just great. I mean, they told a story vividly, and in bright colors. Superman and Batman were my two favorite characters… For the comics I could afford, I… And I was lucky I had a couple of buddies who are twin brothers, and their parents were a little higher, financial scale, so they bought them all the new comics, as soon as they came out. And I would come over and they’d let me read them. I’d say, “Hey, you guys are all right. I don’t care about what anybody else says about you.”

Jim: What era of Superman and Batman are you reading? Because I don’t know your age.

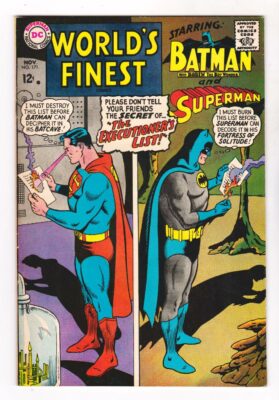

Professor Foster: Silver age. It was like the early ‘60s, and Curt Swan is my favorite Superman artist.

Alex: So, what’s the year of your birth then?

Professor Foster: 1953.

Alex: Yeah, okay. This kind of the approximate year of birth of a lot of our guests, it seems. It’s early ‘50s, yeah.

Professor Foster: It was free, and cheap entertainment. And before you got to the Arrow, everybody told us we were going to die and go to hell if we read comics. It was a great time. Actually, it got better after people said that because that way, now we really wanted to read them.

[chuckle]

Jim: So, you were reading Curt Swan drawn Superman, and probably, you were around during the “New Look” Batman around the time of the shows, so Infantino’s new look.

Professor Foster: Absolutely, but you know the Batman annuals were reprinting stories from the ’50s before I was old enough to read them. Man, I ate those up, because Batman was just more dynamic. I mean, you couldn’t cross a roof without having a giant toothbrush or a razor, or something… It was great.

Jim: Yeah… I love those giant annuals, on all of that.

Professor Foster: Oh, man…

Jim: So now, did you just limit yourself to those two characters at that point? Or did you step into Justice League, and The Flash and all those other characters?

[00:05:01]

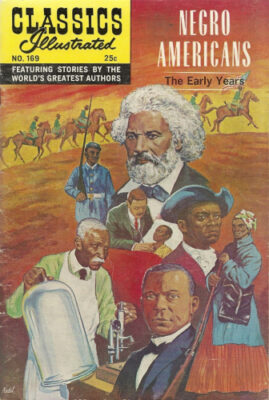

Professor Foster: Every Superman title, I pretty much read, including Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen. World’s Finest, of course, was obviously, combining my two heroes, I love that one. But my parents cleverly got me into Classics Illustrated. And then my cousins read all the Harvey Comic books – Hot Stuff, Spooky. And my sisters love the Archie… Yeah, my sisters, it wasn’t me… Never me…

[chuckle]

I had a really wide range of comics I was looking at. Even some Charlton Comics, occasionally would drop by off my way. Some old EC, my dad brought home a box of those, one time. It had a real heavy mildew smell… Like I cared…

Jim: Oh, that’s great.

Professor Foster: I just went through those, man.

Jim: So, which ones, the horror books, or the science fiction?

Professor Foster: Yeah… All of them.

Jim: All of them?

Professor Foster: Yeah. Had a nice selection. I used to love the fact that… This is something that the critics of comics books never got… Something bad would happen to you, only if you weren’t a good person. If you were an evil person or you had an evil plan, if you kill somebody for their money or you kill somebody’s husband so you could go out with their wife, you know what’s coming for you. And that’s the part, us kids, were looking for.

Jim: Oh, yeah. EC was really good about that too. That if you were cheating on your girlfriend, you were probably going to end up with your head taken off and used as a bowling ball.

Professor Foster: Yeah, or served up to somebody with the eyeballs still in it. [chuckle]

Jim: Yeah, don’t sell tainted meat because you’re going to get it. [chuckle]

Alex: [chuckle] Tainted meat, that’s so true.

Jim: All right. So, it’s interesting, you haven’t mentioned Marvel yet. Did…

Professor Foster: When Marvel came out, I was hooked. But before that, I was a big DC fan, or a lot of different publishers. But when they brought out Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, those are two I kind of read. Doctor Strange, I loved.

Jim: Oh, yeah.

Professor Foster: And then, as they moved into more titles… Captain America was okay, I liked him. Thor, not so much. Ironman, okay. But Spider-Man, primarily. Because, first of all, as history tells us, he was the first teenage superhero, if you don’t count Superboy and Robin. They were sidekicks. Spider-Man was on his own right, and he had a real complex life.

Jim: What was your thinking about… Now, with the EC Comics, they actually dealt with race, especially in the Shock SuspenStories and things. But in others too, they actually acknowledged that there were other people. Not so much with the comics that you’re talking about.

Professor Foster: It’s true. Now, that’s funny, in DC Comics, as I got older, and I started looking at the images, over and over again, I had noticed that the only time they have a black person in a DC Comics was when they were at the UN. And then they weren’t African-Americans, they were Africans.

Alex: Yes.

Jim: Yeah, Had the whole… All the iconographic images of it.

Alex: Yeah, the outfit. Yeah.

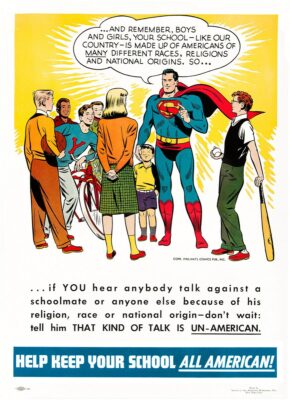

Professor Foster: Yeah, but ironically, they used to do a bunch of public service announcements in the books. And there, you could see people of color. Of course, they’re in poor countries, being served food, and building schools and stuff like that… But the was pretty much it for the longest time.

Alex: Yeah, Jack Schiff was putting out a lot of those ads in DC Comics.

Professor Foster: I did a piece on those on at the Popular Culture Association in Nashville Convention, and I just had the time of my life because I had all these examples. And people who had never seen them, didn’t know pretty much what I was talking about but they had some good advice… Be a good citizen. Be open to other cultures. That was good, but that was the only time you saw it.

In fact, I read a Superboy comic where Superboy goes to Africa and every stereotype’s in play, but in the first two pages of the book, they had this ad talking about “We’re all brothers.” I say, “Hmm… Yeah… I see that. Right now, I see the brothers thing.”

[chuckles]

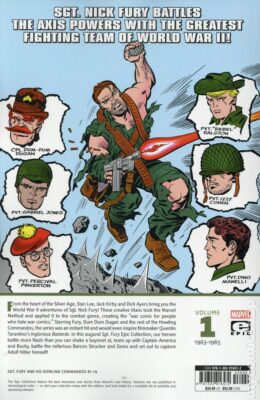

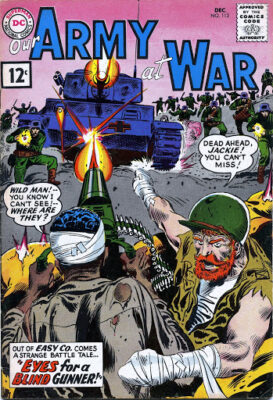

Jim: When there were… I mean, some of the genres, even in the DC Comics and in the Marvel Comics, allowed for black representation. I’m thinking of Gabe Jones and the Howling Commandos, and Sgt. Rock. There was one black soldier and…

Professor Foster: Sure… Gravedigger

Jim: In each…

Professor Foster: Yeah. Gravedigger.

Jim: Yeah… Well there was Gravedigger too… So, you had some of that stuff… Did you seek those books out? Were you happy or pleased to see black representation or did it matter?

Professor Foster: I noticed that it was missing but it didn’t actually detract from the story. But, it’s funny you should mention that because… The non-superhero characters, I saw, that were people of color were in Marvel.

[00:10:05]

Peter Parker’s high school had a black kid in it. Peter Parker had walked through …

Jim: Yeah, and Robbie Robertson.

Professor Foster: Yup… Then they had…

Jim: I mean, he had a real job.

Professor Foster: Had a black cop. You know, like you’d see them at any point in time, and it wasn’t like, “Well, you have to wait till some Negros come along so you can go arrest him.” I mean, he was doing his job. And that was what stuck out in Marvel.

Alex: Yeah. It seemed like Stan Lee was more progressive than Carmine Infantino when it came to stuff like that.

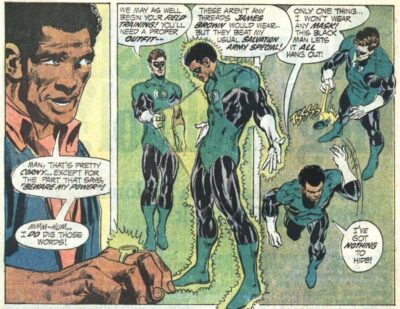

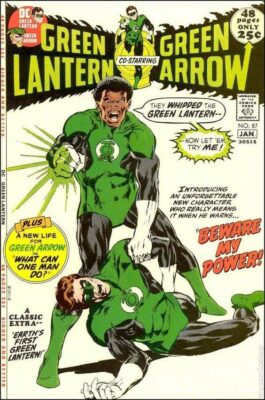

Professor Foster: I met Neal Adams at a show. I brought my entire collection of comic books and different stuff too, in New York. And I didn’t know who he was but he introduced himself to me and his son. And he said, he was standing in one of the editor’s office, and it was like they were asking for a new Green Lantern. And they were talking about him doing another blond guy. And he said, “I’m like, I’m sick of this,”

So, I said, “Listen, do me a favor, come with me, over to the window. We’re in New York City. Look out there, what do you see?... You see people with every ethnicity. Why are we only representing one?” I said, “Look man, you got to have help us out. You know we have to represent what the reality is. That’s what comic books have the opportunity of doing.”

And he said that’s how he got Stewart as a black Green Lantern.

Alex: Yeah, John Stewart. Yeah. He’s a great character.

Professor Foster: Oh man, still to this day.

Jim: That run, for me, changed, probably growing up as southerner, I was 11 or 12 when that first, Green Lantern - Green Arrow… With the, you done a heap for the “orange skins” and the “purple skins”… That was a defining moment for me. I always list that as one of the things that changed my life, in terms of, it woke me up - in a real way.

Professor Foster: I like the cover, where they show John Stewart, without a Green Lantern mask. And how Jordan asked him, “Well, why aren’t you wearing a mask or why aren’t wearing a mask?” He said, “Look at me dude, you think nobody’s going to know I’m black [chuckle] when put a mask on? No, I’m not doing that, get out of here.” He had some bite to him. He had some flavor. Because let’s face it, Howard Jordan was kind of like a tight ass.

[chuckles]

Jim: Oh, totally. And they got that. Denny O’Neil understood that and that’s what he did with the character. I mean, Green Arrow would say, “You’re a tight ass”, basically.

[chuckles]

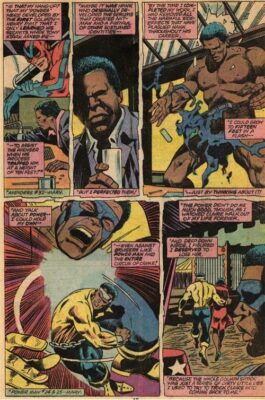

In the Avengers, when Professor Bill Foster actually appears in the comics…

Professor Foster: 1967… Never forget it.

Jim: Were you there? So, you read that?... Because I remember that issue… Because that was a stand-out character too, that that’s a scientist. And it wasn’t like just a one issue appearance. He became, not a significant part of the Marvel Universe until later when he gained powers, but he was a character, and a recurring character.

Professor Foster: Yeah. I was at… More people… Actually, people kind of hit me to that because I didn’t really notice that until later. And I started looking back when he became Black Goliath. That’s when I kind of got it, because he had the introduction at the top of the page; in the first page of every book, on all the five issues. And I just went back in time to see who he was and where he was. And it turned out that he’s the guy that Henry Pym asked about, “How can I get this. I’m having difficulty with controlling my size thing.”

I said, “Whoa. That’s just outrageous. That’s sweet.”

Jim: And they introduce him and then they bring in the Sons of the Serpents. It really is… Marvel’s doing stuff that’s very different from any of the other companies.

Professor Foster: And then you got Black Panther coming out in 1966, which is like “Whoa!”… Where were we in America in 1966?

Jim: Were you reading that in real time? Or is that something that you discovered after?

Professor Foster: Oh, dude… They introduced them in the Fantastic Four, how was I not going to read them? It was great.

Jim: Okay. All right… So, that must have been really something.

Professor Foster: And it’s was funny, is that even then, there were people who had never picked up a comic book were actually convinced that Stan Lee was naming him after the Black Panther’s Political Party. It’s close, if you look at the timelines for both, but no, here was no way that was a crossover.

Jim: No.

Alex: Yeah, I think technically, timewise, he may have done that three months before the political group.

Professor Foster: Yep.

Alex: I think it was almost a coincidence because there’s a delay in printing, by the time it got out anyway.

Jim But I think there was a reference to the party, in a newspaper or a magazine, that may predate it. I’ve argued with Arlen Schumer about this before, and that was fun.

Professor Foster: Oh, man. [laugh] But it’s funny, being… It’s that you know how… I clued you guys on the geek boys. They don’t like coincidences. They don’t.

Jim: Yeah.

[00:15:00]

Professor Foster: So, that’s okay…. But no, I don’t think so, but it was like amazing. When they took the Fantastic Four to Wakanda, and they’re super scientific and the spear that’s not a spear, it’s a ray gun. They have rituals and a fine tradition. I was just like, “What a time, they couldn’t have timed it better.”

Alex: Yeah.

Jim: Back to your history, because we can get lost in the comics, and we’re going to for the next hour or so…

Professor Foster: No problem.

Jim: But let’s talk about… Educationally speaking, so you’re reading comics, do you put it aside and move on science fiction or some other thing? Or do you stay in comics and continue reading that? And what happens, in terms of, do you decide you want to be a professor? Do you decide you want to write? Did you ever want to work in comics? Tell us about that next stage, now that you’re like a little bit older.

Professor Foster: No problem. I was a voracious reader like I said, and science fiction was a major genre. I mean, I went through my school’s library like a wildfire. (Robert) Heinlein was one of my favorites, Norris, Norton, Samuel Delaney; I read all of those guys. I love their work.

Comic books were taking me the same way, it’s given me a world of fantasy but… It helped me in science class, if you can believe it or not… Junior high school science class, one day, my science instructor says, “Okay, I’m going to give you guys a property of a metal, you tell me what metal it is.” I was the only guy in class, thanks to reading Metal Men, I knew every metal. I got the answers right.

But at the same token, I had people… Not my parents… People… I was from a big church going family, so you’re always going to have somebody with an opinion, and didn’t know how to shut up… They were telling me that that kind of books are going to rot my brain. “It’s a waste of time… Don’t read those funny books.” And I just said nothing. But I say a bunch now, because I’m still thinking, “Yeah, you were right. They’re not going to take me anywhere, except to Germany, China, Australia, Britain… Yeah, I didn’t go nowhere. I should put those comic books down. I wasted my life.”

[chuckle]

But yeah, I was a simultaneous reader. Like I said, I couldn’t not read. Once I’ve picked that stuff up, and found out that opening up a book, I can go into another world, that was it for me. I even tried reading novels from other eras, and novels not necessarily written for boys. I was a big Nancy Drew fan… See if I can figure out the mystery before anybody else in the room.

Alex: Nice.

Professor Foster: Then I come to find out the books I was reading was like, what… They were 20 years old, and they’re still producing Nancy Drew.

Jim: Were there any genres that you just thought, “I just can’t handle this because it’s just too damn white. There’s no reference to my…

Professor Foster: [laughs] There was a lot of them.

Jim: I’m thinking of fantasy especially. I mean, Tolkien is awfully white.

Professor Foster: True.

Jim: In all of that, and I love it. But there is no space… Whereas with science fiction, even if it’s by metaphor, it slips in all the time. And I don’t think it does in fantasy, nearly as much.

Professor Foster: No. No, it didn’t. It’s interesting. I don’t… My awareness of people who look like me in books was kind of like… It was kind of dulled for a long time. I think, maybe towards my last part… Oh! I know what actually… You asked me what genres I read… This was about the time, late ‘60s, early ‘70s when Zap Comics came out.

Jim: Yeah.

Professor Foster: And they didn’t care who you were, everybody’s made fun of. Drugs, sex, and rock ‘n roll… I got to tell you, I just said, “Whoa.”

I read a book that featured Richard “Grasshopper” Green, and I said, “This guy must be black because he’s just too damn funny.” The people were afraid to talk race, and he talked about it upfront.

Jim: So, when you’re reading and you would see these images from people like Robert Crumb… You were good with that.

Professor Foster: I know some people like if you said, “Good morning”, they would’ve said, “What do you mean by that?” That wasn’t me. The idea is, I had a sense that he understood. He ironically grew up in Philadelphia, or just outside. I’m looking at somebody, and I just got a sense when somebody is trying to be hurtful in what they’re saying or not. And I’ve never felt like that. He was being funny. And I can’t stop laughing till I start choking. And then I get, “Oh, hey, that’s offensive.” “No, it wasn’t.” But I’ve met some people who are just like everything is offensive. Then I can’t help you because that’s not how I roll.

Alex: And that’s something you mentioned in the book, is that… Because there’s some of the younger people that look at him as a bad person.

[00:20:00]

You analyzed him in your book as saying, “Well, he offended everybody equally and that it was because of that that you appreciated kind of where he was coming from in that sense.” And you don’t feel like he should be cancelled in some way, over the stuff he’s done. Is that right?

Professor Foster: Yeah. I think that’s a bit much. I think that we had people we were censoring comics books. We had people who were having comic book burnings. Gad, that was an awful image, wouldn’t it, what country did that take us back to? And I didn’t feel that was necessary at all. You don’t like…

There were all kinds of comic books. There were religious comic books, and I read those because I came from a very religious family. I love the books that were written about the lives of Jesus or the great prophets.

So, I had a full rounded education, in terms of things that I could reach for. It wasn’t like comic books were evil and death. Besides the fact that comic books of the ‘60s, and the ‘50s were kind of mild. The idea is that you never really saw anybody kill anybody, unless it was an imaginary story.

Alex: Right.

Professor Foster: Lex Luthor was a bad guy but he only killed Superman, an imaginary… Nowadays, who knows what could happen… That’s why the Comic Book Code was in place. But no, I never came after guys… Particularly since I’ve met guys later on, and I’m very fortunate, like Larry Fuller, and Richard “Grass” Green again. I’ve met them in person. And they’re talking about what they did those days, they’d just laugh.

Alex: Yeah. Yeah. That’s cool.

Jim: I want to get you into college. Tell us about your education, like what did you want to do as a career? And how did you go about it?

Professor Foster: It’s funny. I started writing very young. I didn’t start writing well, till I got through college. I started writing for the school newspaper, for the literary magazine, I wrote for the news service, editorial… I just, it was an explosion for me. I’d been writing stories since I was young because I was inspired by the books I was reading.

So, when I got to college, mass communication-journalism was a straight forward run for me, I knew exactly. I’d friends that didn’t know what the heck they would do in college… My parents, college was serious. If you’re going to go to college, you better have something there to do. So, I took it very seriously.

And I’d met all kinds of people there as well. If you wonder… In fact, one of the guys who became the founder of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles went to UMass at the same time I was there.

Alex: Oh, yeah?

Professor Foster: Oh, man…

Jim: Which one?

Professor Foster: The fat guy with the glasses.

[chuckle]

Alex: Oh, that’s probably (Peter) Laired.

Professor Foster: The one that married the really attractive woman, and if I say, “What the hell happened there?” [chuckle]

Alex: Yeah. And then Kevin Eastman married Julia Strain. I know that. Yeah.

Professor Foster: Oi, they do… Life is full of mysteries.

Alex: [chuckle]

Professor Foster: And you think about Connecticut, here’s something I didn’t mention that I didn’t realize when I moved here is that, a lot of cartoonist and comic writers live here. Once they’d make it big, out of New York they came… Right up the road to Connecticut, and just took the commuter train down there. So that worked out really well for me to meeting people.

Jim: When did you do something related to comics, on a professional level?

Professor Foster: Oh, interesting. I think it must have started writing about them in college, because I had this interest. I didn’t have… Okay, I got to tell you a story that you’ve heard more than one time… My parents threw all my comic books out after I moved out.

Jim: Oh, yeah…

Alex: [chuckle]

Professor Foster: I’ve forgiven them now, thanks to the therapy. But I had to start my collection all over again, so, I’m starting in a brand-new era. And I had… No, please don’t get me started on what I had. I’ll just tell you what I went from there, because that would be a long story by itself.

But no, I had started reading everything again, and like you said, there’s the new flavor in comics. DC was trying to get with it, Marvel was just going, you know… They had women superheroes, and they had…

Alex: Now you’re talking in the 1970s, right?

Professor Foster: Absolutely, bro.

Alex: Yeah.

Professor Foster: I graduated in ’75.

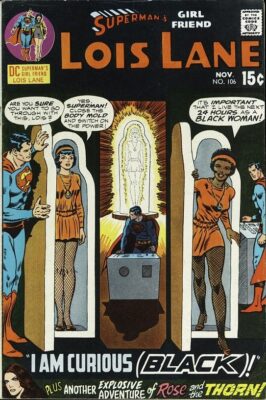

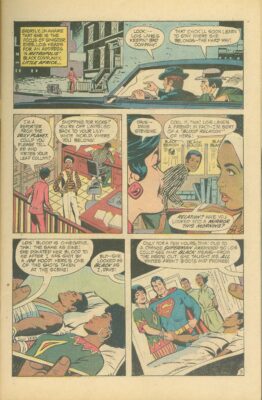

Jim: So, was that good or grimacing, when you would read, I Am Curious (Black)!, or you would see Little Harlem… Or Little Africa in Metropolis…

Professor Foster: I’m sorry… It was just funny, bro. Come on… Little Africa, give me a frigging break.

[chuckles]

Okay, Lois Lane turns black for 24 hours. Man, that should do it, 24 hours is long enough. And how fortunate for her, her boyfriend, who happens to be Superman, can change her, from white to black. And the interesting thing was, that wasn’t the only place that story was taking place. I have a copy of True Confessions Magazine from that same era. And on the front, they have a white woman, blond hair, blue eyes, you know, attractive. And she says, “I turned black.” And there’s another picture where… “Who would be fooled that you were a black person?”

[chuckle]

They just darkened the skin, and put a wig in her. I said, “That’s just funny.” And It’s just like a training on stereotypes.

[00:25:02]

That black people, of course, would be speaking in very stereotypical language. They wouldn’t talk to her, like they didn’t talk to Lois Lane. But once they think she’s black, it’s all, everything is cool… That just makes you ignorant. But I also appreciate it because, we go through stages. We go through tokenism. We go through patronism… We try different images, and the freedom we try that, I think is what we should be.

Anybody… Just look at what they did for women. I mean, women were… How many years, Sue Storm, when she first thought that she was like just cute and posing and… Let’s face it, kind of dumb. As time goes on, she’s become like the leader, more than one time.

Alex: Yeah.

Jim: Oh, yeah. But those early days, The Thing would take her over his knees and spank her. I mean [chuckle] they’re horrible.

Alex: Yeah, I mean, because Stan and Jack were kind of doing romance comic stuff in that Fantastic Four.

Professor Foster: And also, they… That reminded me of something… Oh, Marvel Girl, when she first joined the X-Men, it was the same thing. And two, somebody just made me realize that in one of his thought balloons, Professor Xavier is saying, he’s in love with her.

Jim: Oh, yeah.

Alex: I remember that. Yeah.

Jim: Yeah, that’s creepy.

Alex: That confused me many years later. I was like, “What?”

Professor Foster: Creepy [chuckle]… And not just a little bit…

Alex: [chuckle]

Professor Foster: [chuckle] Whoa, Professor… Whoa.

Jim: Now, Marvel’s got like a bunch of those creepy things, whether it’s Clea sleeping with Ben Franklin, or it’s the Ms. Marvel thought-rape.

Alex: Yeah, that’s the kind of freedom they had a little more freedom to do whatever. Yeah.

Professor Foster: When you first introduce the characters, you’re trying to figure what’s going to work out. But yeah, no, I had a kind of a clear sense of what’s important and what’s not because I was working on those same issues. That someone doesn’t look like me, does that mean that they deserve to be treated less than me?

Well, I had been treated less than… And I didn’t like it. So, I’m not going to do the same thing to somebody else. I got to do better. And when the comic books show that that was great,..

Jim: So, and then I’m going to turn it over to… But at some point, did you decide, nobody has written about African-American comic characters in the way that they should because… We interviewed Trina Robbins, a couple of times, and…

Professor Foster: Oh, big fan of hers.

Jim: And Trina said, nobody was writing about the subject and so… it wasn’t that she set out to be a writer but she said, “Nobody else was doing it, so I had to.” Did you feel that way?

Professor Foster: Yeah. I had to kind of bring attention to it because no one else was. The best thing where I am right now, where I sit right now in comics, is that I’d be able to find all kinds of writers. People who like had gone off into obscurity and I’ve pulled them back. Young people I see at shows. I immediately go to the table, “This is who I am, please send me copies of your work.” So, I become the lodge stone and that’s a role that doesn’t upset me at all. But back in the day, not so much, my brother. Really not.

Alex: Yeah. I had an epiphany as well. There’s a whole, another side to comic history. I had that in Trina’s Women in Comics book, but I had that same, with yours on Looking for a Face Like Mine. No one else is looking at it in that way. And what I want to do with the audience, and us to talk about, and this is your specialty, you’ve run museum exhibits on this. You’ve been in a couple of documentaries, Superheroes: A Never-Ending Battle, and then Comic Book Superheroes Unmasked; both nationally aired.

So, you’ve been on TV talking about these stuffs, this particular area is a specialty of yours. Let’s go through kind of a timeline, starting with the Yellow Kid, and moving to the present a little bit. There’s quite a bit there but…

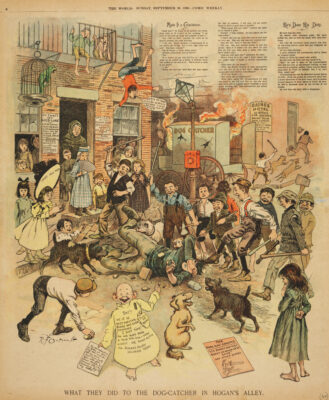

You had mentioned… I’ve watched one of your interviews, and then I also read your book as well; the Yellow Kid 1895, Hogan’s Alley… Now, a lot of the early comics strips like the 1890s, I’m talking about before everything was nationally syndicated and homogenized, and kind of whitewashed in a way… In the 1890’s, they were showing like local New York life in the Yellow Kid, and you were mentioning that there’s like a gang of kids and the yellow kid was one of them, there’s some African-American kids. Tell us about that scenery and then move us forward through time like with Krazy Kat and stuff like that.

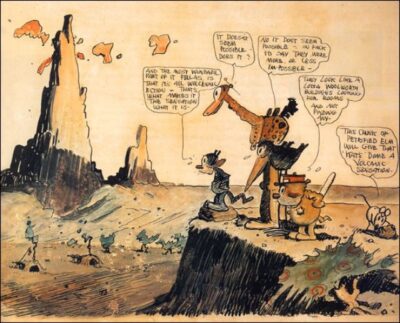

Professor Foster: Oh, no problem, brother… Krazy Kat, how much time, you got?

[chuckle]

The Yellow Kid, basically, if you look at the neighborhood photographs, it’s like… And you can’t tell somebody’s Irish by looking, unless he’s got one of those little white pipes in his mouth… Or the Jewish kid has a yarmulke, and the black kid, obviously a little more obvious for him, you can tell. Sometimes, you couldn’t even tell if the girls were girls because they’d be wearing pants like the boys.

But it was sort of like the art gang kind of theory, the idea is that these are just kids.

[00:30:00]

And they’re coming from different places, they’re speaking differently, but they’re getting along. Now, the adults can’t do it but the kids can do it. In fact, our gang made that main town center team. It’s kind of an American team.

And you’re right, because in the city… I used to kid with my students of my communication class about that, is that if you’re living next door to somebody, you live in one to an apartment next door to somebody, you know exactly what’s going on there. You know when there’s a funeral. You know when there’s a wedding. You know when there’s an argument. The walls are paper thin.

And here you understood that everybody was the same. All those - blah, blah, blah… They always fight… Yeah, you were doing the same thing last night. So, you get the chance to have the sense of how… Our experiences are pretty much the same. We’re going through the same thing. Nobody was really rich but then nobody was really poor. And if you ask me, I’d tell you, my family wasn’t poor but if you look at, compare us to somebody else or contrast somebody else, that was true. So, they started with that.

Now, you’re moving to the 1920s, 1930s and comic books have taken on a place of their own. I think I mentioned that when everybody was in bootlegging and making all kinds of illegal money, get down the place’s stow away when the IRS came by. Suddenly, comics became a place where they could hide those profits. No one said that about DC, no one says about… The best kind of what took place, that suddenly, they had all these cash. In fact… can you guys see this?... I don’t know.

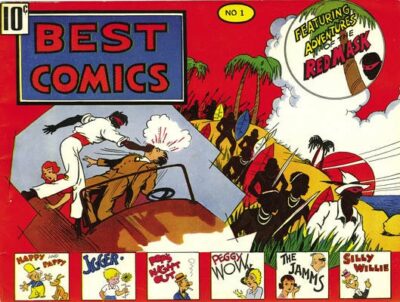

Alex: Yeah, best comics?

Professor Foster: Yeah.

Jim: Yeah.

Professor Foster: Okay.

Alex: Oh, yeah! I know that character. Yes.

Professor Foster: The Red Mask.

Alex: The Red Mask.

Professor Foster: First black hero in a comic book. A year before Negro Hero, All-Negro Comics came out. No one knows who wrote it. No one know who drew it. And when the people found out that he was a black superhero, they tried to put out another one where he turned white. And that just disappeared off the face of the Earth.

Alex: Yeah, I noticed that the coloring was inconsistent. After a couple of issues, I’m like, “What is this?” Now, George Herriman, there is some discussion in his lineage that he had some African-American heritage. He did stuff also besides Krazy Kat like before Krazy Kat kind of became his thing. But there is one, I think it was called Musical Mose, or something like that.

Professor Foster: Lil Mose?

Alex: Yeah. And it was about a black character that was trying to pass himself as white, in a white society. And there were some physical bloopers that had happened. Do you feel he’s expressing something? And what’s your take on that form of comedy back then?

Professor Foster: Well, here’s the interesting thing, Herriman came out of Louisiana, I think probably really near New Orleans. Of all the places in this country, that place is where race-fixing was taking place on a regular level. But if you were white, it didn’t matter what you were. So, people said, he was trying to act like he wasn’t black. I suppose he kept his hair cut short, and he always wore a hat. But then, you had people who would say, “Well, you’re crazy. He took off whenever he felt like it.” He was a dark-skinned guy.

But it talks about the kind of… What’s the word I want?... The kind of sickness about race that we have in this country, about you can’t be too dark or people passing… I had to explain to my students what passing is. They have no idea, that they have seen it but they didn’t know it was called that. Okay. I had to explain to them what the paper bag test was. They didn’t know what that was either. In Louisiana, believe me, that went on all the time. Some of my favorite novels are about those days where it would be like…

I love Krazy Kat. Of course, my introduction to it was, when I was a young kid, the animated Krazy Kat. It was made by the same people who made Popeye. So, you know, you just move from one to the other.

But no, I don’t feel anything like getting kind of skullduggery was going on, that he was trying to hide who he was. Unless… I think his kids said the same thing. And the South… I don’t even want to put on the South. In America, if you’re having kids, and suddenly, one of the kids were dark, a couple of things could’ve happened. But what do people think of the first thing? They think of the worse possible scenario. And men never got blamed, women always got blamed. And that’s kind of like the legacy of slavery and racism, as well as, against women.

So, I just think it’s just people kind of caught up with that. I don’t know if anybody ever took it seriously. I don’t know if he ever lost any jobs, he was just too damn good.

Jim: When you first heard his name, when you first saw pages of Krazy Kat, did you know at that time that he was black or mix race? Or was it something you found out later on?

Professor Foster: Actually, something that people were discussing later… Like I said, I go to the Popular Culture Association Conferences.

[00:35:00]

And there’s always somebody doing the extreme, long, and not necessarily interesting paper on that as the major theme. I’m like, “Uhmm, I guess that’s an interesting point…” But in the end, I had to make the same decision I made about Superman and Batman, love their books, just notice that there were no black people there. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t love their books.

Alex: Right, that’s cool.

Jim: Once you found out, did you read Krazy Kat, the characters, as black?

Professor Foster: No. I did read to see, but maybe I had missed something because I longed for that possibility. That maybe, something was being said, or he was saying some message… But no, I didn’t get any… I didn’t, and I’ve read some stuff where the subtext was a lot less subtle, and I said, “Whoa, somebody here has a problem.”

One of my students wrote a book. He wrote his own comic book. And the title of the book is called Whigger, effectively, white nigger. I thought it was brilliant. Because, first of all, nobody around would even say that word, because they’re so afraid of being brushed with the tar brush. But he was a good writer. He told the story very well. He said, he gets tired of being the white guy surrounded by black guys but he makes that really cool so the only thing that people are complaining is the white people or black people who didn’t know him. His buddies would just look at him and laugh… They didn’t…

So, the idea is that how do we get along, which is that ultimate message on what we read and what we promote. It’s got to be the most important thing a story is telling us.

Now, nowadays, you can be as nihilistic as you want to be in the telling of a comic book story or a graphic novel story. But I was raised in the age where, if we’re not saying something that’s going to promote us, then what are we doing?

I understand the apocalyptic is an interesting reading, but in the end, maybe there ought to be some stories that kind of balance that off. Okay. And that’s what I’m looking for, is the balance.

Alex: Yeah… I like you have a positive attitude about a lot of this stuff.

Jim: I’m curious on one thing though, and go back to Alex… But in terms of, you look a t Krazy Kat, and you look at Little Nemo and they both are two masterworks of that era, let’s say, and… Do you hit a point where you say, “I like Little Nemo but it’s hard to get past the racist aspect of it”? The African kid that’s along with it that’s got the bone in the nose, or… certainly looks like that even if it doesn’t actually have the bone.

Alex: In the ‘90s cartoons, they replaced him with a squirrel or something like that.

Jim: Squirrels are good.

Professor Foster: It’s funny, I… It’s interesting. I think, one of the reasons I read a bunch of old cartoon strips is because I was interested in what lifestyle was like back in that period of time. My parents talked about it. My grandparents talked about it. I didn’t know anything about it. but the race thing, yeah, you kind of notice that.

Who are the major characters? And when you show a black character, what do you show him as? Do you show him as speaking slow and Pidgin English, and not being clever? But then, I did a piece for Hogan’s Alley Magazine where I talked about Henry, the kid who never talked, never had a mouth… Never had a conversation balloon.

In a surprising number of his strips, he’s got black friends, or black kids in the neighborhood. In fact, he even had one place where he sees the black man with four kids going into the ice cream parlor, Henry stops next door to the shoe shine parlor, comes back out, he’s a black kid. He used shoe polish on himself because he wanted free ice cream… You see, that’s funny.

Jim: Ah, that’s interesting.

Professor Foster: Yeah… Now, here’s one that I don’t know if anybody have ever mentioned. Little Lulu, when she was appearing in ads in Saturday Evening Post, a lot of anti-black in Little Lulu. Never got to… Only once or twice in her animated cartoons. did you get a chance to see it. But I was stunned by that. Saturday Evening Post, whoa… What the heck?

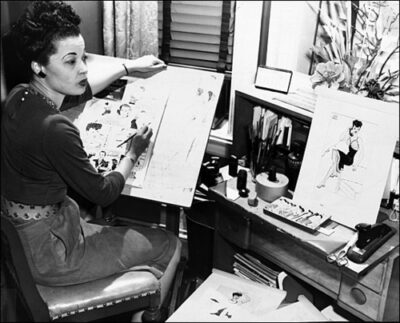

Alex: Let’s talk a little bit about Jackie Ormes, 1937 going to 1940, and then there’s a later run. The Torchy Brown strip, so that’s just kind of amazing that we have a female African-American cartoonist doing newspaper comics strips and they’re syndicated… Is it, mainly by black newspapers? Is that what was going on?

Professor Foster: Yeah. That’s exactly right.

Alex: And how amazing is this that she was doing this in 1937?

Professor Foster: Yeah, I am telling you, it was an interesting period of time, and she was very prolific in that. And how she portrayed the character, an environmentalist, a nurse.

[00:40:01]

Went back down South and came back… I can tell you, from my family, when they left the South, there were nothing that would get them back. But she had an appreciation, there was a call, and a calling, and that’s what she did. So, she’s a character much to be truly admired. And then Jackie Ormes as a female cartoonist, you’re right, dude, that was a speck amazing.

Alex: Yeah. She just had the artistic storytelling drive, which is amazing that that had happened. Let’s talk a little bit about Will Eisner’s Ebony character.

[chuckle]

You put him into a… You said there were five categories of black representation in films. You apply that to comics as well. Ebony represents one of these five categories that you had laid out in your book.

There is also a 1973 conversation with Ebony White by Will Eisner, that you applauded in your book as well. That you applauded it. What’s your take on the Ebony character? The movement that some of the younger people are saying, that we should get his name removed off of the comic industry awards… First, what’s your take on Ebony? What was your impression on his 1973 conversation? Tell us about that.

Professor Foster: I’ll tell you what, I’ll start of my conversation with Will Eisner. I don’t know how I got lucky enough to do this. But San Diego Con, and he was always swamped, and so, I decided I’d come back later. I came back and like literally, there was no one… It had to be lunch time. Nobody was around his booth. So, I had said, “Mr. Eisner, I’m a big fan of your work…” and I talked to him about… I said, “What do you think about how people felt about Ebony?”

He kind of paused for a second, because it’s obvious, that’s the first time he’s been asked. And he said, “Well, depends on when you ask me.” He said, “Sometimes, people have said that it was a great idea to be inclusive, and other people said how dare you have a despicable image of us.” And he said, he got awards from NAACP at one point, and he said, “In another point, they completely condemned it.”

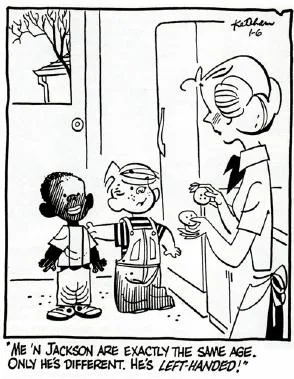

That’s interesting to me, he also had a black police officer who was in more than one strip, in more than one comic. And he had one where Ebony, because a black girl turns him down, decides he’s going to go back to school to get rid of his southern accent. He said he doesn’t want to be recognized as a minstrel… You have black soldiers… So, if I was drawing characters, I would be real careful about who I painted. But at the same token, I don’t know if you guys remember the creator of Dennis the Menace.

Jim: Hank Ketcham.

Alex: Hank Ketcham. Yeah.

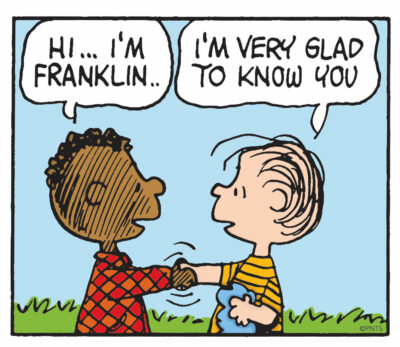

Professor Foster: Yup. Hank Ketcham came out with a black character about a year, maybe two, after Charles Schulz introduced the black character.

Alex: Franklin.

Professor Foster: Franklin. And he did not get the same reaction as Charles Schulz got. People came after him with almost guns and knives. He was in Europe at the time, and he got a wire saying, “Get back over here.” They’re crashing in the offices, destroying property… His goal… His response was this, he said, “Wait a minute, every cartoon character is a caricature of somebody. Find somebody who looks like Mr. Wilson with his big ass.”

[chuckle]

“Or Dennis’ father who has a nose like a nose cone. Or Dennis himself who looks like a tramp with a load in his pants. That’s what I’m doing.” Your critics are big, but the idea is that people were, as I said, “I can’t make anybody less sensitive than they are, when they see an image that they think is really negative.

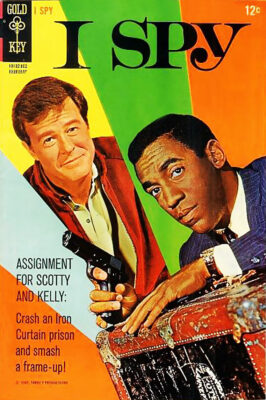

So, Ebony, I didn’t feel insulted because, on top of everything else… I got a question for you guys, like I used to do for my student… You remember the old TV show I Spy?

Jim: Yeah.

Alex: Yeah.

Professor Foster: Robert Culp, Bill Cosby. Okay, here we go. I want you to think about a typical episode. They’re getting into a car, who’s driving? Is it Cosby or is it Culp? If it’s Cosby, is he the servant? If it’s Culp, it’s because he’s the master. Or does it not make a difference.

Alex: Right. Yeah, because sometimes, people will get their own impression of something.

Professor Foster: And so, I think that’s the same … And we’re going to see it continuously, until somebody comes out with a character that’s just so stereotypical that they’re just going to… And/or to be done for that point, Okay? Because there got to be artistic freedom on one side, and you got to be telling the story on the other side. And we all think that every point has to be… You have to hit these numbers on every story you do. When does that’ve ever been true? Because that’s been changing dramatically.

Think about a character like Spawn, who was a black guy when he was alive but now, the skin’s burned off.

[00:45:02]

But people still think of him as a black superhero. I have a friend who says, “No, I don’t want no dead guy as a superhero.” So, it’s such a yin and yang. But for me, unless… When was the last time I was offended by a character?...

Oh, okay… I collect all kinds of comic books. So, I collected one that was put out by the American Nazi Party. And so, you’re going to have a kind of appreciation on what kind of characters they showed on there… That I just screamed. You know, you wasn’t trying to be nice to nobody. You’re trying to make a real important statement about what you think about other races and other religions. And the more cruel and violent you were to those members of those races and those religions, the more you thought you were making your point. Got you. Not lost at all.

Jim: But you don’t really have to go all the way back to the Nazis to be offended by…

Professor Foster: Oh, no…

Jim: I mean, like there’s American comics that I’m sure…

Professor Foster: Oh, god, yeah… They never had an important role, they were only shown for surface… protection, like on the cover, never seen inside the book. There weren’t any black superheroes. There were not black heroines… And yeah, so the absence, and then people who did appear, were they something to be admired? Nope, not for the longest time… You’re absolutely right.

Alex: Yeah. I noticed you had kind of two perspectives, kind of happening at the same time, and they’re valid, and they’re both true. It’s there’s that one aspect of, we should be represented better but then there’s another aspect of, and you said this in your book that, “It’s better than nothing and I love the comics for its form and I love the history of it.” And that you appreciate it for where it was. It’s kind of interesting that you have both of those happening at the same time.

Professor Foster: The world’s a big place, and what’s one of the biggest problems we have right this minute, this time in history, is that if you don’t think the exact same was as I do, not only must you be punished, but you must be punished severely.

Alex: Yeah.

Professor Foster: I think that’s horrible. But here’s the thing, I’ve seen enough, of people of color creating their own comic books, and that’s the excitement for me, and it never ends. And then I see them move into mainstream comics and do their own books. So, we’re at the point where you had nothing on the screen, to the point now you have, on any number of points of view and that’s the only way it can be. No one black person can represent the entire race. No one woman, can represent the entire gender. And yet, somebody will always say, “Well We got one.” Now, that’s called tokenism, and that’s not a good idea.

Alex: Yeah. Right. True. Now, in talking about African-Americans making their own comics…

Professor Foster: Oh yeah.

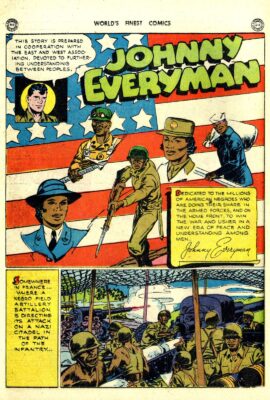

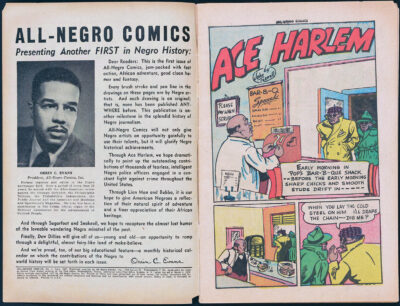

Alex: So, as a segue into it, you mentioned… This is kind of interesting. I like kind of throwing this in. But in 1945, World’s Finest Comics #17, there’s actually a tribute to African-Americans serving in World War II called Johnny Everyman. That was pretty cool. Then a couple of years after that, you’d mention it earlier, All-Negro Comics. And what was interesting was you put it… It was by Orrin Evans… You had an excitement in the way you wrote about it, in that African-Americans having control over their own imagery. And that you had mentioned that that was something that was especially meaningful. Tell us about the significance of All-Negro Comics.

Professor Foster: Orrin Evans was a reporter, and he was more than just a reporter. He was actually the guy who created the Negro journalism organization. He was not afraid to get into a cop’s face, which is even then, at that point in time would have been horrendously dangerous. But he said, “He’s either going to be straight, or they’re going to be…”

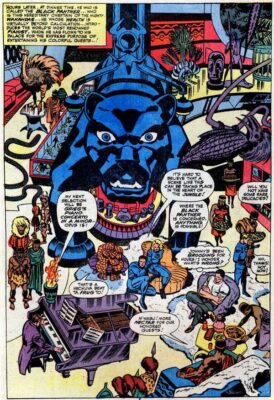

He said, he got tired of seeing comic strips that didn’t have people like him. So, when the paper he was working for went out of business, he… We just pretty certain that all the guys he got were all black. But he got a bunch of guys who he knew could do the job, and they put out their book. He was told and pressed that he couldn’t sell this book… He sold this for 15 cents while every other comic book was selling for 12… Which was a major thing to do. In full color, he did the book. Not only the color but the inside. He did, a great African king, he did a black detective, he did black fairies… He took the story to wherever he could. I think that was amazing.

It only lasted one issue. I happen to have one copy because I happen to be at the right place at the right time. That’s how it gets done. And then, you get other people to sign it, maybe we ought to try this. So, you get Negro Heroes… Who was that? Dell, or was that… I think it was Dell.

And then you have in 1965…

[00:50:04]

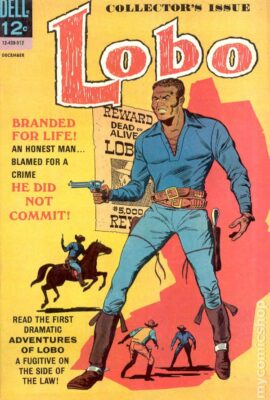

Alex: Yeah, Lobo?

Professor Foster: Yep. First comic book that features a black character as a main character. Now, I met both the guys who put that book together.…

Alex: Oh, yeah? That’s cool.

Professor Foster: Got lucky. I happen to be doing an exhibit on Long Island, and this guy walks up and he said, “Hey, that’s my work.” [chuckle] “I thought you guys were dead!”

[chuckles]

And then I met the other one because I did a couple of shows when I was teaching at my college, and the guy shows up. He lived not very far from where we’re doing it, and I couldn’t believe it. I had him come down to the… There’s a big black comic book convention out in Philadelphia every May. I had him come down, and they gave him a Founders Award. He’s a white guy, but he was the guy who said, he read a book called the Black Cowboys, and he said, “We need to do something.”

Alex: Yeah, because that’s a real thing in history, that it should be told. That story needs to be told.

Jim: And there were black westerns all the time. I mean, that was very common, African-Americans westerns during the serial period.

Professor Foster: But sadly, they were only shown in black theaters, and only one night a week. But yeah, it was like a specialty film. It took me years to figure this out because by the time I was going to the theater, you’d go anywhere. But to be only allowed to go on the “crow’s nest” and only on certain days of the week… and they would cut certain scenes out of the movies so it didn’t look like the black folks and white folks are getting along. I thought, “Geez, people before me had to go through all those.” Through a lot of troubles, a lot of mistreatment.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right.

Professor Foster: And I never understood that. Because it wasn’t my experience. It’s like riding at the back of the bus, if I could put that point in. It’s that, when I was a kid, back of the bus is where the fun was… That’s where somebody was playing cards, that’s where somebody had a guitar, or somebody was passing around a bottle of something. But before us, it was never like that. And you need somebody to kind of give you a sense of that history.

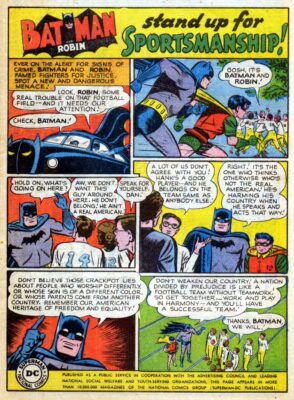

Alex: Before we jump too deep in the ‘60s, because ‘60s and ‘70s are their own pretty amazing story in this, but in the ‘50s, there are a couple of notes. One, you mentioned, Batman #57, Batman and Robin, stand up for sportsmanship. Probably, Jack Schiff’s statement that racial fighting weakens our country. So, that was an interesting thing. It’s cool that you found all these, and that you put them in your book like that.

Then you also mentioned, and Jim will find this interesting, is 1964-ish, you have the War Comics. You have Our Army at War, Star Spangled War Stories, Sgt. Fury, Howling Commandos. And you had mentioned in the book when it came out that you weren’t sure why but war stories tend to be a fertile ground for a racial discussion. Why is that? First, what’s your impression? And then, maybe Jim can weigh in on what he thinks it is too.

Professor Foster: Oh, no problem. A particular story I read when they… In fact, real early in the run of Sgt. Fury and the Howling Commandos, they had a guy who joined their commando unit. They had an Englishman, they had an Italian-American, they had a Jewish guy, they had a black guy, and they had a southern guy. And they had Sgt. Fury, who is from New York, like from Hell’s Kitchen.

And this guy, when they bring them in to the barracks… They say, “Here, you’ll be sleeping next to this guy.” “I’m not sleeping next to a black guy.” “Get that Jewish guy…” [chuckle] And they call them on it. They said, “You’re a bigot… We work as a team. If we don’t, we all die.” And sure enough, this guy, because he wants to be a hero and he’s like struggling to fight when they’re right in front of the Germans, and it’s like they’re all going to get killed… He gets the message but it’s not so obvious. “Oh, gee fellas, that’s great… It’s a small world… “

That’s not what happened. The idea is that, he gets it but he can’t admit it to them. That, I liked about the story. Now, on the other side of that, in terms of realistic, there was never an integrated unit in the United States Army, ever. Least of all the commandos. But despite that, I loved the fiction. I ate it up. They had all separate skills. They worked together. They looked out for each other… Come on, who wouldn’t want to be part of that gang.

Alex: Yeah, that’s true. Jim, what’s you’re take on the war genre and racial discussion.

Jim: Well, I think in comics, it was really clear. Because, I think of Blackhawk’s, and Chop-Chop, and so many, or young allies… Where Kirby does a horrible black kid. Whereas when they bring in Sgt. Fury, Gabe is as competent as anybody, and one of the cooler characters. It’s a little silly with the trumpet but…

Professor Foster: The trumpet, yeah.

Jim: But it’s ok. Later, they use him, in terms of music, and that story that takes place in France and the treatment of black men.

[00:55:03]

That’s kind of brilliant. I really… So, they were good on that. The story that the professor is talking about, doesn’t that end with Gabe actually giving blood to the racist?... It’s a little heavy handed in terms of the last comments, the final panel but it’s good. And I think in film, you don’t get a lot of that, until probably after, Fury and Rock, and those stories. I think comics are leading the charge, so to speak.

Professor Foster: Absolutely. Well, I think it’s also that… When you guys were talking about Marvel earlier, that they felt that they could do it. DC, maybe not so much, and that Marvel ran with it. Maybe they could make a change about something. It was like they were… All of a sudden, Sgt. Rock’s… I mean, Sgt. Fury is like black, one day. But the idea that he encourages his men to have an appreciation for each other. And I don’t know if DC was, at that point in time, I don’t know… Was open to that kind of storytelling.

Jim: But none of it compares to that EC story, where the white guy goes, and he’s being celebrated and he finds out that his fellow black soldier is buried somewhere else and is not honored. And he calls them all out on race. That’s ahead of its time like nothing else.

Professor Foster: Love that story. I love it because you had to read it carefully, and you had to keep up where he was going with the story.

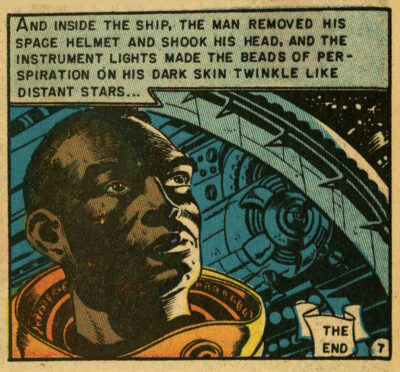

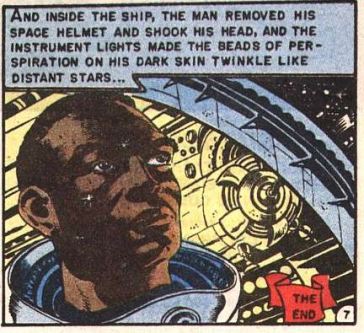

Alex: Speaking of EC, did you like that Judgment Day story? Where the astronaut… This is 1953 now. We’ll go back to the ‘60s right after that. But the astronaut talks about, it’s at the robot planet and there’s one color robot versus another. There is this kind of bigotry going on, and then the astronaut says, “You guys aren’t quite ready yet.” And he takes off his helmet, he’s an African-Americans man. And then there’s some weird thing with Bill Gaines, and the Comics Code was saying, “Well, you can’t have sweaty beads on an African-American’s head, it’s too sexual.” And they gave him all these…

Professor Foster: Oh, my god!

Alex: They gave him all this hell and they wouldn’t distribute the comic over it. Or not that they wouldn’t distribute, but the Comics Code won’t approve it so the newsstands wouldn’t distribute it, until he complained enough. What’s your take on that story? And is that still a powerful story?

Professor Foster: That reminded me, or maybe it was probably… I couldn’t tell who inspired it but I’m guessing, that they later inspired the Twilight Zone for the same thing, where Rod Serling told stories about racial inequity, all of the damn time. It must have made the censors crazy.

But yeah, the idea that… It’s like you don’t want to tell the story but you got to tell the story. No one censoring you… “Well, we’re not prejudice, but we’re not talking about it.” Then you’re prejudice. Shut up. Okay.

[chuckle]

They just couldn’t get it… So, I love that story and it’s surprising to me how well known that story has become. I have a friend I just sent a copy of the comics page. In the next issue, where people wrote letters about what they thought of the story. It was interesting that it was kind of an even mix on what people thought they liked and what they didn’t like. And one guys says, “Well, if you like niggers so much, why don’t you go live with them.”… Whoa! How do you find a pen? And then, somebody else said, “Thank you. Thank you for telling the story like you told it.” They took the chance. If they hadn’t, nobody would have said anything, but I think the world would have been poor for not having heard it.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right.

Jim: Since you brought up the Twilight Zone, can we just for a second and go off and talk about The Big Tall Wish?

Professor Foster: Go for it.

Jim: You know that one?

Professor Foster: I believe I do.

Jim: The boxer that becomes a…

Professor Foster: Ahh… Was that Ivan Dixon?

Jim: Yeah. Yeah, with the little boy and dreaming and things. That’s just an example of what Serling was doing, but it’s just amazing.

Professor Foster: It’s just so sad that the main voice of the story is his hand or his feel for the story. It took years for somebody to come back to get with that same feel. Because the one that they did back in the ‘80s was like… Ah oi, not good.

Jim: Well, there were a couple of good episodes, and there’s a few I really like. But no, it’s not the same. Neither was the (Jordan) Peele one that was on CBS… It’s hard to put that back.

[01:00:04]

I as big as a Twilight Zone fan as you probably are. In fact, my son’s name is Willoughby.

Professor Foster: [chuckle] You are a big fan.

Jim: You can’t get more than that.

Professor Foster: No, you cannot, my brother.

Alex: [chuckle] So, as far as the ‘60s, we talked about Robert Crumb, we talked about Franklin in Peanuts, so now, we’re going to enter the ‘70s. This is interesting because the ‘70s, there’s like maybe a lot of movements of the ‘60s started to manifest. There’s a delay, and then suddenly it starts showing up in pop culture, more in the ‘70s, almost like an explosion almost.

Professor Foster: Absolutely.

Alex: Where you have, you mentioned Inner City Romance, by Guy Colwell, Super Soul Comics 1972, Richard “Grass” Green.

Professor Foster: Absolutely.

Alex: Don McGregor’s Jungle Action Series with Black Panther, Luke Cage. So, tell us about his movement. Tell us about, as you were reading these in real time, what did you feel was going on?

Professor Foster: Oh, man, it wasn’t easy. It’s that the counter-culture was taking over… Let’s get on the reel, people were like… When you see a major trend would come in or a major wave is coming through, it’s making money and you want to make money too. So, you try things out, that are making… When you start seeing a lot more women, manifest themselves in the comic book world, and not just as superheroes, but as policemen, or police chiefs in some cases, head of government agencies, and politicians. It’s easy for them… Like now, we have a template, now we can do something here now that…

The first ones were, like we said, they’re kind of like in humor, “Oh, I got to go to senate and pass a bill, but first, I got to get my nails fixed.” But I’m remembering plainly, the number of stories I read, where they were telling… I had friends telling me, they told them, “If you, don’t care how many degrees you have, every woman here, starts in the typing pool.” Or, “You are not going to be able to get this job. Why should I hire you when you’ll just get pregnant, and go get married to someone and I got to train somebody else?” Right to their faces, with no shame, whatsoever. What I’m saying, gad that’s horrible. Because I’m coming in to the age where women are trying to get a fair shake and fair shake is for everybody.

So, the ‘70s is that. The language changes… Or ask anybody you know about Luke Cage. And that’s the last time you had a black guy say, “Sweet Christmas.”

[chuckles]

Jim: Well, it would have been on the Netflix show, two years ago.

Professor Foster: Oh, man… Who was I talking to?... I was talking to one of the guys who did the Milestone Comics, and he was cracking me up with that. He said, “Yeah, me and the brother are sitting around, and I heard somebody say, sweet Christmas” [chuckle] I said, “Please, you’re killing me.”

But, also, there was another phase too, was that every black superhero had to have black in front of his name. And that kind of got to be a joke. Even now, it’s still kind of a joke. But I understand what that was, being black was important to say. And if this is the only way you can say it, that’s fine. Okay.

Jim: Did you see the Harvey Birdman episode with Black Vulcan… Have you gotten to that one yet Alex?

Alex: Yeah. Yeah. I’ve finished the Harvey Birdmans, they are funny.

Jim: Black Vulcan is on the stand, and he doesn’t want to be called Black Vulcan. And he says, “I said that to Aquaman, why don’t you call yourself White Fish?

[chuckle]

Interview ©Comic Book Historians 2020