Comic Book Historians

As featured on LEGO.com, Marvel.com, Slugfest, NPR, Wall Street Journal and the Today Show, host & series producer Alex Grand, author of the best seller, Understanding Superhero Comic Books (with various co-hosts Bill Field, David Armstrong, N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., Jim Thompson) and guests engage in a Journalistic Comic Book Historical discussion between professionals, historians and scholars in determining what happened and when in comics, from strips and pulps to the platinum age comic book, through golden, silver, bronze and then toward modern

Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians.

Read Alex Grand's Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland & Company here at: https://a.co/d/2PlsODN

Series directed, produced & edited by Alex Grand

All episodes ©Comic Book Historians LLC.

Comic Book Historians

Gary Groth Interview: Publisher, Comics Critic, Historian part 1 with Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview Fantagraphics publisher, The Comics Journal co-founder, and Genius in Literature Award recipient Gary Groth, in Part 1 of a 2 parter covering his full publishing career starting at age 13, his greatest accomplishments and failures, feuds and friends, journalistic influences and ideals, lawsuits and controversies. Learn which category best describes ventures like Fantastic Fanzine, Metro Con ‘71, The Rock n Roll Expo ’75, Amazing Heroes, Honk!, Eros Comics, Peanuts, Dennis the Menace, Love and Rockets, Jacques Tardi, Neat Stuff and the famous Jack Kirby interview; and personalities like Jim Steranko, Pauline Kael,Harlan Ellison, Hunter S. Thompson, Kim Thompson, CC Beck, Jim Shooter, Alan Light and Jules Feiffer. Plus, Groth expresses his opinions ... on everything! Edited & Produced by Alex Grand.

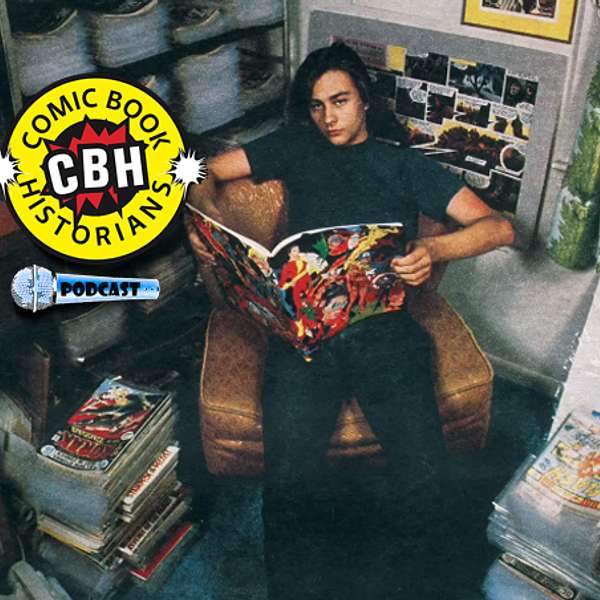

Images used in artwork ©Their Respective Copyright holders, Photo ©Chris Anthony Diaz CBH Podcast ©Comic Book Historians. Thumbnail Artwork ©Comic Book Historians. Music - standard license, Lost European.

CBH Interview Series

Comic Book Historians Podcast

#TheComicsJournal #GaryGroth #Fantagraphics

Alex: Well, welcome back to the Comic Book Historians Podcast, I’m Alex Grand with my co-host Alex Thompson. Today we have a really fun guest, publisher, comic book historian, childhood comic fan extraordinaire, Gary Groth. Gary, thanks for being with us today.

Groth: Happy to be here.

Jim: So, I know you were born in 1954, a son of a Navy contractor. You’re actually born in Buenos Aires?

Groth: I was born in Buenos Aires; my dad was in the Navy. And I was born there because he was on active duty, and he was stationed in Buenos Aires.

Jim: And then, was he still in the Navy when you moved to Springfield?

Groth: Yeah, he was. He was in the Navy for about 30 years… Let me see. Let me walk that back. He joined the Navy, I think in ’39, and so that means he would have retired from the Navy in ’69. I think that’s approximately right. From Buenos Aires, we moved to Williamsburg, Virginia. I was about two.

Jim: How long were you in Williamsburg?

Groth: Until I was five. So, I think we were there for about three years. Then we moved to Springfield, Virginia which is a suburb of Washington DC.

Jim: I spent would spend my first 25 years in Richmond, Virginia.

Groth: So down the road.

Jim: Yep. I know. But very different, still. You guys were less confederate than we were, back in Richmond.

Groth: Well the whole Washington DC area is sort of an oasis in Virginia. You drive 20 minutes south, and you’re in the Confederacy.

Jim: Yep.

Alex: But Jim is in no way affiliated with that now.

[chuckles]

Jim: No, I’m an expatriate, pretty much. But I did grow up there.

Groth: Where do you live now?

Jim: Los Angeles.

Groth: Okay.

Jim: I moved out here in 1985. I’ve lived here longer than I ever lived in Richmond.

Groth: Yeah. Same here, in Seattle. I’ve lived here longer than any place I’ve ever lived. Including my upbringing in Virginia.

Alex: So, you’re pretty close to your father then, it sounds like. Because he was part of your, kind of pop culture upbringing, wasn’t he?… In some way.

Groth: Well, yes. I mean, he was. He was of his generation, World War II generation. He died five years ago, at the age of 99… So, he had me when he was 39, I think. He was a little older.

I was kind of an oddball kid. And I don’t think he quite understood because he grew up in Queens. He was born in Queens. And his ambition was to be short stop for the New York… I don’t know if I’m going to get it right, like the New York Dodgers… I don’t know. It was like a New York baseball team. And that was his ambition in life, which he didn’t fulfill which is why he joined the Navy when he was 19 or 20.

And I had no interest in sports. I couldn’t do sports. I was terrible at them. It was the worst thing I experienced in high school. And so, I retreated into comics. And he never read comic books, he read comic strips. So, he didn’t quite understand what I was doing but he understood the passion. And I think he understood that if we were going to be close, and if he was going to be part of my life, he was going to be part of that.

He was very supportive. Both my parents were very supportive. But he helped a lot doing the nuts and bolts work when I put out a fanzine, when I was 13 years old. He did all the bookkeeping which he was very good at. He was very meticulous, which I am not, very detail oriented, and he kept the ledgers. He kept the books.

I put out the fanzine… I’m sure you’re going to get there. I put out a fanzine when I was 13. It started off as kind of a typical, terrible fan worshipping little fanzine. We called them Crudzines back then. And he kept all the books. We would get orders in, and I think it cost 50 cents. So, people would send quarters taped to cardboard. We would open those envelopes, we would take the quarters out and he would very meticulously put them in a ledger, with the name of the person and we’d have to mail the person the fanzine, and he probably handled a lot of that.

When I printed the fanzine, we would go to his office, and they had a Xerox machine there. That’s when Xerox machines were much more rare. People didn’t own Xerox machine, companies and the government owned a Xerox machines. So, we’d go to his office and Xerox my fanzine, and when we come home, we would staple it together. We would staple the fanzines together, together. So, he was very much supportive and very much a part of what I did back then.

He also, another big component of our lives was, that he basically introduced me to movies. Every Saturday or Sunday, after he got home from playing golf, we would go to see a movie. We’d get in the car and go see a movie.

[00:05:04]

Back then, in the ‘60s, they didn’t really make movies for kids. There were a few, but primarily, they did not cater to children. And so, what I saw, were the same movies that he saw. They were like war movies, they were detective movies, mysteries. I mean, they starred John Wayne and Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, that whole generation of actors. And that’s probably where I discovered my great love of film; by going to see a movie every weekend.

Jim: Yeah, I want to talk about that a little bit. I had the same experience because you didn’t have the other distractions and so, dad would take me to see High Plains Drifter or something, when I’m like completely inappropriate to go see it.

Groth: I saw that with my dad. I’m a little older than you are, because I was more or less a grown up. I was probably about 21 or 22 when I saw that, and I actually took my dad to see that movie.

Jim: Yeah, that’s… I remember that one as …

Groth: And that would be pretty inappropriate for a kid.

[chuckles]

Jim: We’re talking about the fanzine, but I want to go back in time a little bit and talk about Metal Men #5.

Groth: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jim: Tell us what the significance of that.

Groth: Well, I discovered that comic in my pediatrician’s office. I wouldn’t say I was a sickly child but I had asthma, and I also had allergies. Both of which I still have. And I would go to the pediatrician’s office and get allergy shots every week or two. And I think I discovered that comic, sitting in his office; he had a pile of comics sitting there. It is the first comic I distinctly remember seeing. And I forget… You probably know what year that comic was…

Jim: Oh, yeah, I did my… ’64.

Groth: ’64, okay. Yeah.

Jim: It was a December- January release, so you would have been nine.

Groth: Right. Right. I might have read some comics before that. I have vague memories of reading comics like Hot Stuff and Richie Rich, and that whole line of kids’ comics and I don’t know, I can’t remember where that fell, if it fell before that or after that. But it was that Metal Man comic that was a revelation to me.

Jim: Yeah, I read that from there, you just were all in.

Groth: I just went ape-shit, Yeah, I just started buying comics. Of course, I started buying DC Comics.

Alex: Now, did the Gorilla covers help you go more ape-shit over the comics you’re reading?

Groth: They did not. I was not aware of the gorilla trend. Although, it was apparently happening when I was in prime comics buying mode, but no. But yeah, that was part of that whole goofy DC period, which I probably enjoy.

Alex: Right.

Groth: I think it was, anyway.

Jim: You were kind of DC focused for that first year, but by ’65, ’66, you moved to Marvel, pretty much. Right?

Groth: Yeah. It probably took a couple of years. I’ll tell you one funny story, it’s possible, the first Marvel comic I bought was Strange Tales, which I’m sure you know, they split the comic between the Human Torch and another character, what was it? The Thing?

Jim: It was Doctor Strange.

Groth: Doctor Strange and the Human Torch. And I think I actually bought that comic because I had mistaken the Human Torch for The Flash. They were both red, so they seem like the same character. So, I remember buying it, taking it home and reading it, and realizing this was a different reading experience. It was just, all the rhythms of the Marvel Comics were entirely different, the drawing was different. DC’s drawing was much more domesticated. There was something cruder about Marvel.

Alex: And DC, weren’t they kind of subsumed in that smooth New York, Dan Barry type aesthetic. [overlap talk}

Groth: Yeah, a lot of Kurt Swan, Wayne Boring, yeah, they were much slicker than Marvel… So, I noticed that intuitively. I mean, I was probably, whatever, 12 or something. But then I realized there was this whole other comics brand out there. And I started picking up on those.

Gosh, the first Fantastic Four I bought was #33. And again, I don’t know what year that was, but it probably was ’65 or something like that.

Jim: And you started doing mail order catching up on the earlier issues, right?

Groth: Yeah. I had to have all the early issues I’d missed, which I eventually got. So, I would order them by mail, mail out of dealers back then, and you would order them by mail.

One of the great moments of my life is when my folks drove me to Passaic, New Jersey. There’s a place called Passaic Book Company, and I would order comics from them. And that’s when you can order a back issue of Spider-Man for like a dollar or $2, or something like that.

[00:10:00]

So, it wasn’t outrageous. And I would order a couple of comics, and then I’d be utterly thrilled. I’d be waiting for like a week, for their comic to arrive in the mail. And of course, when it got there, just opening the package was so exciting.

So, somehow, I talked my parents into driving to Passaic, New Jersey. It was a family outing; it was probably a round trip in one day. And they were a big back issue comics dealer, and they might have been a book dealer, just a general book dealer as well. But they had this one gigantic room with nothing but comics in it, and it just blew my mind. I was like 14 or 15 at the time.

I remember going in there, I mean I was just pig heaven, I guess. I didn’t have enough money to buy all the comics that I needed to buy but that was great. Yeah, I collected it all. I would buy back issues, mostly of Marvel. I don’t remember buying back issues of DC. I think I was more addicted to Marvel. I was more obsessed with Marvel.

Jim: Were you only reading superhero stuff at this point? Like not their westerns or their romance or…

Groth: I was reading every single Marvel Comic. I was reading all their westerns. I even bought Millie the Model, which I obviously had no interest in…

Jim: I did too… [chuckle]

Alex: Patsy and Hedy? Something like that?

Groth: Absolutely.

Jim: Yeah.

Groth: Absolutely. I mean, just because it was a Marvel Comic, I want to keep abreast of all the Marvel Comics. I joined the Marvel Merry Marching Society.

Alex: You’re one of those guys, That’s awesome.

Groth: Yeah. Got no prices. I’d out grown it by the time Foom came around, so I did not join that. But yeah, there was a period of three or four years when I happily drank the Kool-Aid.

Jim: You had mentioned that your dad read comic strips. Were you interested in those as well?

Groth: Marginally. I would read comic strips but I like the longer form narrative of comics. Even the DC Comics which were I think almost all self-contained stories, as opposed to the Marvel serialized soap opera. So, I think I like the longer stories. I mean I can read the Sunday newspaper strips, and I kind of dug them, but if you read a 22-paged Stan Lee – Jack Kirby story, it’s got so much satisfaction to it than reading a very short… Than reading a third of a page or a half page story in the newspaper. So, I never really picked up that habit. I learned everything about newspaper a little bit later.

Jim: Now, did you quit Marvel before Kirby and Ditko left?

Groth: No.

Jim: Or was it around their departure that helped end it?

Groth: Well, Ditko left around ’69…

Alex: No. Ditko left Marvel in like ’65… No, ’66.

Groth: Did he leave that early?

Alex: Yeah, and then Kirby left in ’70, Wally Wood left… [overlap talk]

Groth: Yeah, Kirby left later. Kirby left in the ‘70… Yeah, no, I didn’t. I kept reading Marvel… Let me see… Well, no, I kept reading Marvels through high school, and I graduated in ’72. So, I probably kept reading through about ’72.

I mean, I have to tell you, I got less interested in the comics themselves, when I was putting out these fanzines, than I was in the artist and in producing the fanzine. I know that sounds paradoxical but I think I became less fanatically interested in reading the comics in the last year or two of my high school, than I was in about being involved in this fandom, and following the very specific artists that I was, and starting to know the artists I’ve met. I started meeting artists when I was… I don’t know 14 or 15.

Alex: How’d that all start? I mean, let us… about Fantastic Four…

Jim: I’m going to get to that, Alex, in a minute. I just want to do one or two things and then get to the fanzine.

Every piece on you that I’ve read was sort of generic, would say, “Influences – Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris.” And my question is, don’t you have to pick a side? How do you do both Pauline Kael and Sarris? And if that’s true, do you lean towards Sarris? And are you an Auteur Theory person?

Groth: Okay. Well, now, this is later. This is like in my 20s, and yes, I did pick a side. The side for me was not between Sarris and Kael. It was between John Simon and Stanley Kauffman, and Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris.

So, we’re talking about film criticism in the 1970s. This gets very complicated… Sarris and Kael clashed, but almost all of the critics who worked in the 1970s… It started in the 1960s and they were looking at works into the 1970s… They were all clashing with each other, and there were camps. I was in the John Simon – Stanley Kauffman camp which was, I think, the more literary side of film criticism. Whereas, Pauline Kael, and Andrew Sarris… Well, do you know a critic named Vernon Young?

[00:15:05]

Jim: Yes.

Groth: Okay. Well, he, again would have been in the Simon – Kauffman… Manny Farber I thought he straddled, you know, the middle. He was somewhere in the middle.

Jim: Boy, he could write though. I’m a big fan of Manny Farbers.

Groth: Yeah, he was terrific. I mean, they were all good. But I do think the best writers, the best plot writers were Simon and Kauffman. Kael could write but… And I love to engage Kael, but there was something about Kael that bothered me. She would tend to write more of, around movies, than about them.

Whereas, I thought, Simon just nailed it. He was so precise in his criticism, and agreeing or disagreeing with the critic was not ever the point. Because I could profitably disagree with all of these guys.

Jim: I deliberately skipped to that because it seemed to me that as much as comics and the influence of comics, as we were talking about, the influence of these particular people helped you formulate your ambitions and your style, as it relates to comics. So, I thought it was important.

Groth: Yeah. It’s absolutely true. You know why? The first film critic I encountered was Dwight MacDonald’s who wrote for Esquire Magazine.

Advertisement

Jim: Oh, that was when you were in college that first… Your professor had you read all of Esquire.

Groth: Yes. Yes. You’ve done some researching…

[chuckle]

Yeah, it was at community college, after my first year of college. And I was flailing around, I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. And so, when you don’t know what you want to do with your life, take a creative writing class. I think that’s what this was. It was actually a creative writing class.

Really, I didn’t really know about writing. All of the writers I read were just second-rate pulp writers. I read, Robert E. Howard. I mean, I could distinguish good writing from bad writing. So, I took this course, and this guy whose name I no longer remember, he really opened my eyes to what good writing was. And one of the things he told us to do was read Esquire.

It would have been 1973, at that time Esquire was running a lot of great writers. They had Dwight MacDonald writing for film criticism. I think Nora Ephron had a column. I forget who wrote the literary column. It might have been James Woolscott, might have been. It was a writers’ magazine at that time. And it really suddenly opened my eyes to what good writing was.

And so, I would read Dwight MacDonald, and then I would go out and buy his book of film criticism. And then, John Simon took over from Dwight MacDonald so I started reading John Simon. Then I would buy his book of film criticism. The first book of his I read was Movies into Film. And that was eye opening because here was somebody who clearly had an enormous amount of expertise, he was an extraordinarily good writer, and who was applying these honed critical skills to film.

Something that I hadn’t truly considered before. And of course, that’s what led me to thinking, well why isn’t someone applying these same skills to comics? And that had been done erratically in the past, very, very rarely, we can talk about that. But that’s what opened my eyes. Then John Simon, he wrote a big essay in Movies into Film about Pauline Kael.

Jim: Oh, yeah.

Groth: Where he attacked her essay, which was called, Movies and Trash, whatever it was called. Of course, I thought, who’s Pauline Kael? And I had to go and buy her books. So, I would take notes about who all of these… Dwight MacDonald, John Simon, and Pauline Kael; I would take notes about who they’re writing about. If John Simon mentions Susan Sontag, I would have to go out and find out who she was.

Jim: Yup. It’s just one, one leads to another.

Groth: Yeah. Yeah.

Jim: Let’s go back to when you’re 14 before you know any of this. But you’re starting your publishing career to some degree, at that point. And I read that by the time you were 17, you were telling your parents you wanted to be a publisher.

Groth: Well, that’s true. Yeah, I think I wanted to be a publisher. The first college I went to was the Rochester Institute of Technology, and the only reason I went to that, is because, my parents had not gone to college, and so they really didn’t know how to navigate finding a college. And so, we were looking for a college, that taught publishing.

Well… There was no such college. I don’t think there were university courses about publishing. And so, the Rochester Institute of Technology was the closest thing we could find to publishing because they specialized in teaching printing technology. Now in fact, of course, printing technology has nothing to do with actually publishing. But neither I nor my parents knew that at the time. So, that’s why I went there, because I wanted to be a publisher. After a year there, I realized that it was not really training me to be a publisher.

[00:20:03]

And that there was no training you can have that would make you a publisher, except being in publishing. And I think that might be, in retrospect, why I started kind of floundering around because I didn’t know how to be a publisher. I knew how to publish a fanzine and make no money, out of my parent’s bedroom, but I didn’t know how to become a publisher.

Jim: I have some questions about the Rochester Institute, and also your journalism aspect of you working on the magazine, but before I do that, I still want to do Fantastic Fanzine, because that’s obviously important; that you started at 14 and you had people like Tony Isabella, and Mark Evanier, and artists like Dave Cockrum before he went professional. You were getting art from Neal Adams, to Bill Everett. How was this happening when you were aged 14? And talk a little bit about that aspect.

Groth: Well, I didn’t have any hesitancy in writing to artists, and I would initially write to them being care of Marvel and DC. And apparently, the companies would forward the letters because I seem to remember… I ran an interview with John Romita, I think, like in 1968 or something like that. And that was done, entirely by the mail. I sent him a letter, and introduced myself, and then sent him questions, and he would answer them. So, I just started doing that.

Alex: Was that through the Marvel offices or to his address?

Groth: Well, I wrote to the companies, and then they would forward… I would write, “John Romita, in care of Marvel Comics.” And they would evidently forward them and then I would get a letter straight from the artist. There was John Romita, or Gene Colan, or any number of other artists, and then their return address would be their personal address, and then I would start writing to them from there.

That was before you could really make phone calls. Long distance phone calls cost a lot of money, and my parents were very supportive but they were not that supportive. So, I couldn’t make any phone calls, but I could write to them. And so, I started doing that.

I started actually meeting artists, like I went to the 1969 New Your Comic Art Convention. My dad drove me up there. My dad’s parents lived in New York. They still lived in Queens, so we could combine this trip, and he must consider this wacky exercise…

Alex: Is that the one that had Hal Foster and Gil Kane were there?

Groth: Yeah. Yeah.

Alex: You were at that dinner with all those tables, that famous picture?

Groth: Luncheon, yeah.

Alex: Yeah.

Groth: Yeah, that was fantastic. That was a fantastic convention. I met all of these people whose work I’d read. I mean, Gil Kane… I knew who Hal Foster was, but I didn’t know him that well but that was my introduction to him, really. And all of these cartoonists were there, Al Williamson was there and I knew who he was. I would meet them and I would get their autographs, that was really a seminal influence on me because they were real people.

Alex: It’s like a pilgrimage in a way. Right?

Groth: Yeah. I mean, I couldn’t have been more thrilled. And then that encouraged me to put on my own convention in Washington, which I did… I think I put on my convention, 1970.

Alex: That’s the Metro-Con.

Groth: Yeah.

Jim: ’70 and ’71, I think. You did two years.

Alex: Yeah, ’70 and ’71, And you interviewed people like Sal Buscema and stuff, doing that right?

Groth: Yeah. Well, Sal Buscema lived in Springfield, and he was one of the earliest cartoonists I met because he lived about 20 blocks away from me. And I somehow learned that he lived in Springfield, which I couldn’t believe. So, I somehow mustered up the courage to give him a call, and he was incredibly gracious, and incredibly patient. I was probably about 15.

He let me come over to his place on a Saturday or a Sunday. And he would sit down with me for a couple of hours and talk to me. And of course, I would pepper him with all kinds of idiotic questions about what he was working on, and the Avengers, the characters he was doing, and who he would like to ink him, and on, and on, and on. I would do this, every six months. For as much as… I’d have to muster up the courage to give him a call again, because I knew I was imposing, wasting his time. And then he would finally say, “Yeah, come on over, and we can sit down…” He gave me a lot of original art. He gave me a lot of pencil pages that were never published.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Groth: He would self-reject them. He would do a page, and he wouldn’t like the story-telling or the drawing or something, and he would just say, “Would you like to have this?” “Of course, I do.” I did and I still have those pages.

Alex: Oh, how fun. That’s great.

Groth: And he did very complete pencils, I have to say.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right. And I’ve read that he was in the military and that’s why he was at that Washington DC area. And that’s why he ended up living close to there. He developed a lot of bonds in that area, and that’s cool, you happen to be right there. That’s awesome.

Groth: Yeah. He was literally like a five-minute drive away.

[00:25:00]

Alex: And so then, when you’re talking to different creators like this, and then like you said with the Comic Art Convention, did you then start to feel pretty comfortable as a journalist, in a way. Like a budding journalist that, “I can talk to these people. I can get answers. I can be inquisitive with them.” Is that the attitude that start to develop around that time?

Groth: I don’t know if I formulated, coherent enough thought to think of myself as a journalist. I mean, I was just such a passionate fan…

Alex: I got you.

Groth: That I wanted to do this. And I’m not sure that at the point I consider myself a journalist or what I was doing was journalism. It was this fan activity.

Alex: Right. And your dad sounds like he facilitated it. He wanted you to get into something fun like that.

Groth: Yeah, yeah. Of course, I couldn’t put on a convention at the age of 16 without an adult signing certain documents, so he was very involved in that. And when I put on the convention, that’s where I really had to interact with professionals, and that’s when I had to talk to them and cut deals with them. I had to get people to come down from New York to Washington, to go to this convention. Which means I had to give them a room. I had to arrange their travel, and I had to appear like I knew what I was doing.

And that’s when I started really… Being introduced to a lot of professionals that had a big impact on my life. People like Bernie Wrightson, Mike Kaluta, that whole generation.

Alex: Right, and there were visual artists as well. They can do fine art, even.

Groth: Well they were great. They were a new generation, about five, six, seven years older than me, which at that time, meant a lot. I mean, they were like grown-ups, and they were forging their lives. And they represented something new in comics. I don’t think I probably had the wherewithal at that time to realize the differences that they were bring to comics but they sort of skewed the whole hack ethos. Comics was really a hack business.

Alex: Well they had the same guys doing comics for like 30 years up to that point. Right?

Groth: Yeah, yeah. And as you probably know, Marvel and DC, there was a period of a decade where they weren’t hiring new artists. They got all the artists they needed.

Alex: Yeah. I read this Stan Lee interview where he was like, “Oh, only… There’s no new artist in but we’ve got this new guy, Jim Steranko. Kind of a fan that likes comics. He turned out pretty good.” That was his 1968 interview. How’d you feel about Steranko when he came on the scene?

Groth: Oh my god, I loved Steranko. I mean, I worshipped his work. I mean, Unfortunately, I worshipped him.

Alex: Tell us about that interview with him in that Fantastic Fanzine, and how you guys met. Tell us about that a bit.

Groth: Well, I can’t remember how we met. I probably met him at the convention. I have a lot of photos of him, that I took. So, I deduce from that I probably met him in ’69 or ’70, ’71, at a convention. I was a huge fan of his work, as many of us were. He was doing work that looked innovative at that time. In retrospect, I think it’s less so but he was doing work that was fresh and interesting, and he was breaking out of the conventional comics format.

Marvel was pretty much a child of Kirby, so every artist drew in the Kirby mode. And even though you can see a lot of Kirby in Steranko, he brought a lot of other influences to it. And so, he looked like this amazingly fresh talent, and as you can probably tell from your own interview with him, he builds an aura of… He creates his own mystique. And he had that mystique going for him then.

He was younger than most of the professionals at that time. He would walk around conventions in turtle-necked sweaters and pink jumpsuits, and wraparound sun glasses. And he kind of holds this self-mythology everywhere he goes. And I was mesmerized by him and his work. It’s a little like escaping a cult, finally, when you realize, “Well, there’s less to this than meets the eye.”

Yeah, I met him. I met him in ’70 or ’71. As you probably know, I worked for him in ’73, I think.

Alex: ’73, yeah.

Jim: We’re going to get to that in a few minutes.

Groth: But, yeah, I did the interview with him. My dad drove me off to Redding, Pennsylvania. I was 16… You can probably track these dates better than I can. I think I was 16.

Alex: Yeah, 1970, it was right after he left Marvel, and he was venting about Sol Brodsky and things like that.

Jim: But he had done a cover of the preceding issue that was inked by Joe Sinnott. That was issue #10, and then #11 was the interview.

Groth: That’s correct. Yeah. What happened was he didn’t do that cover for my fanzine.

[00:30:01]

I bought a pencil rendition from him. And because I also befriended Joe Sinnott, I asked Joe if he would ink it. And Joe who’s an absolute sweetheart, and whose interview I put up on The Comics Journal website last week. The interview that I did with him with two of my friends… I asked Joe if he would ink it because I thought all pencils should be inked. And he inked it, and I ran it on the fanzine.

Subsequently, I interviewed Steranko. My dad drove me up to Redding. I interviewed Steranko during the day, and I think into the early evening. My dad just dropped me off and left us. It was the whole Steranko experience. He lived in a small apartment, it had kind of a muted lighting, there was some soft jazz playing in the background. It was kind of a Chet Baker-ish…

Alex: That sounds exactly like him, yeah. I know that experience. Yeah.

Groth: Yeah, it was the whole experience. It was 1970, you say so I would have been 15 or 16 depending on when in 1970. And it was great, I mean, he tolerated me, which was nice. I was a worshipful fanboy, so probably it wasn’t too hard to tolerate me. But I think he saw me as someone who could be useful to him. And we talked on the phone, not infrequently, which was always kind of exciting; talking to Steranko.

Alex: Was that influential on you, in a positive way, as far as, what path you would go forward in, I mean, I know you had the later, issues with actually living with him and all that. But that moment, that interview, he saw something in you that he felt was special. In some way, was that a positive on you?

Groth: Well, I don’t know if he saw anything particularly special about me. He saw an enthusiastic kid that was putting out a decent fanzine with some rudimentary skills that I think he thought can be helpful later on. So yeah, I don’t think he saw anything particularly promising.

Alex: Looking back, you don’t feel like it was more a positive patriarchal moment. It sounds like you almost have more of maybe a negative… It sounds more negative the way you address it.

Groth: Yeah, I mean, he’s… He said something in your interview. I watched the first part of your interview. And he told an anecdote about him going to Tower, I think it was and going to Sam Schwartz.

Alex: Sam Schwartz, yeah.

Groth: And submitting the brilliant Secret Agent X. And Schwartz apparently was criticizing him and telling him how he wanted him to do it. And Jim said something to the effect that he thought that he was grooming him to be a slave boy. Do you remember that term? It’s kind of a weird term that Jim used, and he almost punched him out. He indicated that he was being condescending.

I heard that. I listened to that a couple of days ago, and it was a little shocking because that’s exactly how I felt, working for him. Except for the punching out part, I never considered that. I don’t know if I’m saying he turned into Sam Schwartz but that was exactly the dynamics.

Alex: No, you’re feeling like a mirror irony, in some way.

Groth: Yeah. I mean, Jim obviously has a gigantic ego, but I thought he could be somewhat, looking back on it, I think he can be somewhat manipulative.

Alex: I see.

Groth: Especially when I was 16, 17 years old.

Alex: Impressionable.

Groth: Yeah.

Alex: I would say this, about Steranko. I love the guy… And you listened, and there was probably a lot of excitement when I was talking to him. and something that I do respect on what he did in the ’60s was, Stan was just telling everybody, “Just do it like Kirby. Do it like Kirby.” And then he actually brought in the influence of movies and things, and different sorts of visuals.

In a field that was with guys that were really old, and were still doing it and they were all doing it, and they were all like stuck in this way. And I feel like he kind of wedged it open, creatively, for some other stuff. Where Stan was like, “Okay, we could kind of get some new stuff going on.” And I thought that’s important.

Groth: Well, I think it’s fair. I don’t know how important it is but I think that’s fair… I think it was Craig Stein who said very emphatically that comics were not movies. And I think Jim was trying to make comics into movies. I mean, I think that was fundamentally wrong-headed that you’re right that he brought that fresh perspective into comics.

He was slicing the page up to many more panels. Trying to imitate cinematic conventions. It’s undeniably, he brought that in. I just think, in retrospect, it just looks pretty hallow. You’re still dealing with the same old crap.

[00:35:03]

You’re still dealing with those pulp soap opera conventions that Marvel traded in, just gave it a new dressing. Borrowing from Eisner, throwing a little of Dali in. I mean, he was throwing in all those references. I tend to think a big influence… I don’t know if you asked him this, but a think a big influence on him might have been Crepax, Guido Crepax; Italian cartoonist.

Alex: Yeah, he definitely knows about those guys. Yeah.

Groth: Yeah. I mean Crepax was slicing up the page…

Jim: I don’t know if we can see it. I got my Crepax book right here.

Alex: It’s blending, Jim, I can’t see it.

Advertisement

Groth: Yeah, I can’t see it.

Alex: [chuckle] It was in the dark dimension.

Jim: It’s your book, that’s all I’m saying.

Groth: It is. It is.

Alex: I would say also that he’s like a unique personality. He has a lot of different skills. When I met him, it’s obviously, as like a 40-year-old guy. So, it’s a different feeling maybe. But one thing I would say is, he’s very incisive, like from person to person, like he can almost read minds, a little bit. And I’ll say that as far as his influence on me, it’s very positive in that he actually like inspired like a lot of my motion comics stuff that I do that he critics it and we go back and forth on it. I guess I just want to get it out there that I highly respect his work and I just want to throw it out there.

Groth: [chuckle] You feel compelled to do that.

Jim: So, going back to Fantastic Fanzine, besides the Steranko interview, because there were others, I was interested in… By mail, back and forth, you’d did an interview with Barry Smith, and he was a kid himself at this point, right? Was he about 19 or 20?

Groth: Barry is five years older than me. So, when i was 15, he was 20, and when I was 16 he was 21. So, yes, I was corresponding with Barry while he was living in England.

Jim: That’s what I thought. How did that happen?

Groth: He started out at Marvel. He was the best Kirby imitator at Marvel. And of course, I loved Kirby, so therefore I love Barry. And that’s why I must have written to him. I must have written to him in care of Marvel, and they must have forwarded the letter to him, and Barry must’ve written to me. I have a bale file of letters from Barry.

Alex: Oh, wow.

Groth: A lot of handwritten letters in Barry’s very lovely calligraphic handwriting. Yeah, we had a correspondence. I forget… I mean, I’d have to revisit all the letters from him to me, I don’t have any letters from me to him, thank god. But yeah, we had a correspondence. He would send me drawings which I published in the fanzine. Nice little spot illustrations of Marvel characters that he would pencil and ink, out of the kindness of his heart. I didn’t pay him a penny. And so, we had a correspondence going, and then I met Barry. The first time I met him was in New York, once again, my dad drove me up to Manhattan. I was probably 16, and Barry was living in an apartment. So, if I was 16, that would have made him 21.

So, I go up the apartment, knock on the door, and he opens it up, he’s like this tall, dapper Englishman, with his great English accent. And I’m just this suburban kid, and I walk in. It’s a big apartment, and my recollection is, it had a piano, bookcases, nice furniture, it was just sort of overwhelming. And we sat down, and I don’t remember if I interviewed him or we just talked. But I spent a few hours with him. He too was incredibly gracious, and accommodating, and patient with this kid. And later on, he told me that that was not his apartment. It was a friend’s apartment and he was staying there because he had no place to live. Marvel wasn’t paying him enough to have an apartment like that. Marvel was only paying enough for a studio apartment somewhere on the village without heat.

Jim: Was he actually on the street at one point? I’d heard, when he first got here…

Groth: I might have heard that. I think, yeah. Marvel probably wasn’t paying him very much. I shouldn’t say that without knowing but I mean, I think I might have heard that myself. But yeah, I think Marvel wasn’t paying artists, like very new artists, young artists, very much money.

I know that when I was offered a job at Marvel, which was exactly at the same time as Steranko offered me a job with him. I don’t think I could have survived on the pay that Marvel was offering me. I forget what it was at that time.

Alex: Is that the main reason you turned that down?

Groth: That was the main… Yeah. There were a couple of reasons. Roy Thomas offered me a job at Marvel, and gave me the salary. I asked my dad, because I didn’t have any experience living on my own, except in college when I lived in the dorm. And I asked my dad, “Can I live in New York on this money?” He said, “No.” So, I went back to Roy and I said, “My father says I couldn’t live in New York.”

[00:40:00]

And Roy said, “Well, that’s probably true, but we can give you freelance work to beef it up.” So, then I thought, “Well, I’m going to be working for Marvel eight hours a day in the office, then I’m going to be working for Marvel all night doing freelance work”, and that really didn’t sound appetizing. And then the other operative factor was that I’d have to give up my car. All of these combined, I very politely turned them down.

Jim: When you were 17, just a couple of years before that, we discussed that you went to Rochester Institute of Technology, which was a leading printing school which I’m sure came in handy, at some point.

Groth: It did.

Jim: But it wasn’t what you were thinking was it?

Groth: I’m glad I went there. It was an academically rigorous school. And unlike anything I’d experienced before because I kind of slept through high school. I was a mediocre student. Little was asked of me and little was given. And this was the first rigorous academic environment that I’d ever been in. And so, I actually had to pay attention.

Jim: And is that where you were working for the magazine and started to actually do interviews in terms of not fanzine but doing it as part of the…

Groth: Well, the college had a magazine; a campus magazine. And I got a job there being a reporter. Which was good, I did stories that they assigned me stories, and so, I was not only learning things, academically, about printing, and design, and typography, and so forth, but I was learning something about being a journalist because I was writing stories that I didn’t have any personal passion for. But they would assign me stories, and so I had to do research, and I’d interview people, and then I had to compose the story.

I remember… This sounds ridiculous but I did a story about the elevators in the campus dorm, because the goddamn elevators were so slow. And I learned a lot about Otis Elevators. Apparently, they’re among the big elevator manufacturers in the country. So, I did my research and I learned a lot about that.

So, I would do these stories with subjects that I personally had no interest in, which forced me and disciplined me to learn how to research. I did that for the year I was there.

Jim: Now, after that first year, did you transfer directly from there to Montgomery Community College or did you take a time off?

Groth: There were six months between those two. I went to Rochester for a year, came back home… Not knowing what I wanted to do or where I wanted to go, but knowing I didn’t want to continue in Rochester. Knowing that that just wasn’t quite right for me. I mean, I didn’t want to be a printer. But then, not really knowing what I wanted to do with my life. I mean, I was floundering around. Which probably accounts for taking a job with Steranko.

Alex: Well, yeah, because I joke that… I asked him a little bit. I was like, “Was it like you were Professor X and he’s like a wayward teen like…?” And he said you guys worked together, he didn’t say much about it.

[chuckles]

Like the Professor Xavier School.

Groth: Right. Right. Well, it’ll be like that if Professor X were a masochist. Yeah.

Jim: [chuckle] So, Montgomery Community College, Northern Virginia Community College, and then working as a clothing salesman. That was all in a certain block of time where you were trying to figure out what to do.

Groth: Yeah. And you can tell, just by that resume that I didn’t know what the hell I wanted to do… Yeah, I was working as a clothing salesman in a jeans shop. I wasn’t like a real clothing salesman. I worked at a jeans place, and by god, I learned a lot about jeans, all the different brands. I did that at the same time, I got a job and went to two community colleges, and I just took courses that I wanted to take. So, I took silkscreen printing at Virginia Community College, and a couple of other courses. And I took that creative writing course at Montgomery Community College which is in the suburbs of Maryland, and probably another course or two there. I couldn’t take that many because I was also working.

And yeah, I just didn’t really know what I wanted to do with my life. I was really at ends, because I couldn’t figure out what to do. I was probably going through something of a crisis because I knew I didn’t want to enter the corporate world. I knew enough to know that I didn’t want to do that. But I didn’t see any alternative to that, so I was stuck.

Jim: In trying to do my timeline, I wasn’t quite sure, did you end the Fantastic Fanzine completely before you started working for Steranko? Or was there some overlap?

Groth: Yeah. Yeah, I did. I think I ended it after I left high school.

[00:45:01]

Alex: And Alan Light published it. right?

Groth: Yeah, he published like two issues of it. I think

Alex: Oh, okay.

Groth: Only two issues of it.

Jim: And that caused some problems down the road, right?

Groth: Yeah, yeah. We had problems too, yeah… I’ll have to talk about some people I didn’t have a problem with but…

[chuckle]

But yeah, he approached…

Alex: [chuckle] Well, we like problematic Groth. That’s like…

Groth: Yeah. Right, right. He approached me. I guess it was my last year of high school, and he approached me. He was creating a dynasty, and he approached me and asked me if I was interested in having him publish the fanzine. And I don’t know, for some reason, I was. I think he was going to take over all the economic headaches, he was going to deal with all that.

That was never something I was interested in. I was never interested in being a business man. My dad did all that work. He was the one who kept all the books. I was mostly interested in just putting together the magazine. I was never interested in that.

So, Alan Light came along and he said he would publish it, and we struck a deal. I don’t know if he was paying me anything, if he was it had to be nominal. But he would pay for the printing, he would deal with all that. He would deal with subscriptions. He would deal with all the stuff I didn’t really want to deal with. But the last issue, I’m pretty sure I published that in my last year of high school, and then I went to college, where I published a couple of other things.

I published a fanzine called Word Balloons, which I thought was a great sophisticated leap from Fantastic Fanzine. which it was, slightly. And I published a couple of other things when I was in Rochester. I published a little comic of Dennis Fujitake’s work. So, I was still somewhat involved in publishing when I was on Rochester.

I don’t know if that answers your question or not. I think I’m just rambling about.

Jim: No, no. You’re not at all. And we could get to a little bit more about Alan Light, once you start Comics Journal, and that first editorial that you did… But we’ll save that.

So, Alex, 1973 and now, Steranko again.

Alex: Right.

[chuckles]

Jim: You’re the Steranko guy.

Alex: Yeah, that’s right. So, now, you already mentioned in ’73, because we kind of gone a little back and forth in our timeline but… Roy Thomas, you turned it down, you started working with Steranko, and I’ve heard some of your accounts of this already… Working with him, and then from right when you stepped in to right when you left, you’ve mentioned a few things that you felt you did and weren’t able to provide your own creative input into Mediascene and all that stuff. But was working on Mediascene, in any way, influential in how you would put your Comics Journal and other publication together.

Groth: It was influential in the sense that that experience indicated what I shouldn’t do. I’ll give you one example.

Now, I was 19, and I was relatively clueless.

Alex: And wayward, you were a wayward teen as well.

Groth: [chuckle] I was wayward. Yeah, that might be putting a little romantic spin on it, but yeah, I’ll take wayward.

[laughter]

But I had some sense of things, and so at one time… All I did in his place was scut work. I mean, I did some paid stuff… I mean I really didn’t do anything that was worth the shit. But you know, Mediascene, you’ve seen it, right?

Alex: Yeah.

Groth: Nobody watching this has probably seen a copy, or cares about it but…

Alex: I have most of them. I think.

Groth: Yeah, I have most of them too. But it’s not still being published, right?

Alex: No.

Groth: And he turned it into… I mean, it was Mediascene and he turned it into…

Alex: Turned it into Preview Magazine, right?

Groth: I mean, it was basically a sort of Entertainment Weekly.

Alex: Yeah, in the ‘80s, it turned into Entertainment Weekly, but in the ‘70s it was still in kind of that comic scene/Mediascene like newspaper print format, where they still had a comics section and they would talk about movies and things. I think it was, once it started publishing, or rather once it started going through Larry Flynt, and it turned into a slick magazine, then it was basically like the pre-Entertainment Weekly of its time, right?

Groth: It went through Larry Flynt?

Alex: Yeah. See, how do I know this and you don’t know this? I don’t get it?

Groth: I stopped following Steranko closely after by 1975.

Alex: There you go.

Groth: Larry Flynt, was he involved in publishing?… Was he a contributor?

Alex: No, no, no. Yeah, he like… That’s who like put out the slick magazine.

Groth: Really.

Alex: Yeah. They never met though. I asked him already.

Groth: It was Jim and Larry Flynt, all right.

Alex: Because you mentioned, I remember I saw… You talked to Barry Smith, you talked about the magazine. I think there was some mention about some of the naked women in the back of the magazine, like that would kind of skeeve you out or something.

Groth: Oh, no, no. I don’t think… No, no. I don’t think so. I had no moral judgement about it. It would support the whole enterprise; that stuff. I mean, he sold a lot… He had a mail order business going. And I gathered that that substantially supported…

Alex: Yeah. Financially, right? Because Eros did the same for you guys at some point, right?

Groth: Yeah, absolutely. Right, right. I don’t remember having any problem with that. I hope I didn’t but I… Where was I?

Alex: Working on Mediascene, did some paid stuffs.

[00:50:00]

Groth: Did working for that pave the way?… I’ll give you one anecdote, and that is… So, as you know Mediascene and then Preview, they covered movies. They sort of previewed all the Hollywood movies that were coming out and then all the comic books that were coming out. Steranko is a little bit ahead of his time, in foreseeing the moronization of culture, where comics become the culture. You know?… They become cinema-culture.

So, Mediascene was full of comics and movies. But this was before movies had become nothing more than comic book movies. So, before movies came out in the theater, he would have previews of them with the title of the movie, a short take and maybe a still. And he would get these stills from the studios, who were sending them to him for publicity’s sake. So, at one point, I came to him, and there’d be a synopsis of the plot… Well, you know what, I’m sorry, I think this came out after the movie. There were reviews of the movies; ostensive reviews of the movies.

And so, I came to him one day and I said, “Could I write some movie reviews? Because, of course, one of my few ambitions was to maybe write film criticism.

Alex: Yeah, critic stuff.

Groth: I said, “I think I could write reviews as good as you’re running.” And I pointed out to a couple of reviews, and I said, “This is not very good. And this is just the plot synopsis.” And the actual critical content of the review was so meager that I thought I could do a better job. And he looked at me and said, “I don’t need you to do that.”

I said, “Who’s writing these reviews anyway?” It didn’t have a name, they weren’t by-lined. And he said, “Well, I just take studio press releases and rewrite them.”

Jim: Wow.

Groth: And so, I distinctly remember standing there, talking to him about this. And I remember thinking, there’s something wrong about that. Passing off rewritten studio press releases as reviews. As independent reviews appearing in this magazine. I don’t think we talked about that much. I think I tried to persuade him that I could maybe inject a little bit of critical content into the magazine, but he wasn’t having it. It’s not what he wanted. It not what the magazine was about. He wasn’t interested.

Advertisement

So, in a way, yes. It did influence me, in terms of what not to do.

Jim: Were you living in the house at this same time?

Groth: Oh, yeah. We were all living in his house. He had a gorgeous big townhouse.

Alex: So, this is a different place than when you had interviewed him a couple of years before.

Groth: Yeah. When I interviewed him when I was 15 or 16, he was living in a small apartment. And he’d obviously acquired enough success to buy this big Victorian townhouse. It was beautiful. It was at least two floors, maybe three, and really spacious, and I lived on the ground floor with Ken Bruzenak. You know who Ken is?

[overlap talk]

Jim: The letterer?

Groth: Famous letterer. So, he and I were on the ground floor and Steranko’s studio and his living quarters were above… I felt about Steranko then is you, apparently, feel about him now.

Alex: No. No, no, no. I’m not saying… I mean, I’m a 40-year-old guy. I’m not…

[chuckles]

I’m not a wayward teen that is worshipping him. That’s not it. I’m not…

Groth: Sure? Because I’m a little worried.

Alex: But I want to throw out there, a couple of things about it. At his time in 1970, or 1970 to ’72… And then you got in on it at ’73 like that… When he put out the History of Comics volumes, and he was doing, illustrations for covers and book covers and things, and he’s putting out a magazine as a publisher, and putting out some pretty interesting designs in general, I don’t recall anyone coming to that caliber of expression, from a commercial and artistic standpoint, before that.

Groth: You’re talking about what year?… ’70…?

Alex: Looking at that. And looking at what he was doing in those few years there. From where he was at that time, I think that’s a pretty interesting person. It’s a unique person. And that’s all I’m saying, and I wouldn’t want to take credit away from that. But I get what you’re saying because when you’re actually with a person day in, day out, and now you’re seeing realities of the everyday thing, that’s a different experience. And I get what you’re saying. I’m not disagreeing in what you guys… I mean, that’s before I was born, right?

Groth: Yeah, and I don’t want you to think I’m conflating my personal experience with my critical judgement.

Alex: Right.

Groth: Don’t think I am. I mean, I try to separate the two. And I think that you have to do that with every artist which is now out of fashion.

[00:55.00]

I like Roman Polanski’s films

Alex: Right.

Jim: Because they’re great.

Groth: But I wouldn’t want to hang out with him alone.

Alex: What did he make? Quaalude Heaven or something?

[chuckles]

No, I’m kidding. I shouldn’t say that. I shouldn’t do that.

Groth: But no, I try to separate that out, so I’m not conflating those two… Sure, you have a point. But when your baseline… And I don’t want to spend the entire time talking about it, Jim. But when your baseline is just the most mediocre hack work…

Alex: Before him.

Groth: Yeah, or during that period, from…

Alex: Right, or even during… Yeah, with the other people

Groth: 1970 to ’75, it was a terrible period in the mainstream comics.

Alex: Right. Totally.

Groth: And you’re comparing him, primarily to mainstream comics, and not to other comics. You’re not comparing him to kind of the personal expression that you found in underground comics; they were championing long before. I mean, what he was doing was rearranging, pulp and comic book clichés, in a different way. So, depending on how valuable you find that, and I don’t find that particularly valuable… Your assessment of him will be based on that.

Alex: Right, right.

Groth: I was looking…

Alex: You’re looking at what it could be. And there is a lot of amazing creative people that came after him, and I get what you’re saying. Yeah.

Groth: Yeah, yeah. I’ll tell you. Here’s one thing. Here’s one area where he might have influenced me. I worked for him for three months, and that was in ’73. I started The Comics Journal in ’76, so that was still three years later. So, I still had three years of living to do. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was kind of flailing around. And when I was working for him, without getting into any more details… And I only worked there for like three months… So, I knew, I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had no idea what I wanted to do. But I did know what I didn’t want to do. And what I didn’t want to do is eat shit.

Alex: Yeah. Right. I knew that.

Groth: I knew that if I continued working for him, I would be eating shit…

Alex: Yeah, that’s like that assistant to Stanley Kubrick, like that guy just got weird.

Groth: Yeah.

Jim: But Kubrick’s brilliant. I mean, nothing against Steranko but Kubrick could kill me and I would accept it.

[overlap talk]

Alex: No, I know. It’s just that assistant that he had just really like he was warped towards the end of all that. I get what you’re saying

Groth: No, no. I’m sure Kubrick did have his idiosyncrasies…

[chuckle]

But I think it’s but a false analogy because Kubrick’s work, even though it ranges all over the place, even though I think Paths of Glory, and Dr. Strangelove are absolute masterpieces. But they’re masterpieces on a level that Steranko can’t come close to. And that kind of goes to the heart of using that analogy. That goes through the heart of the distinction I was trying to make when I started The Comics Journal, between films and comics, and what comics could be. And what they were capable of, and the level of artistic expression that they were capable of.

I mean, I’m leaping a little bit ahead, but that’s the conclusion I came to. Probably over that three-year period from the time I left Steranko until I started The Comics Journal. I educated myself over that period…

Jim: Well, let’s talk about that period because…

Groth: Yeah, that was a rich period. I mean, in my life.

Jim: So, you’re there at Steranko’s, Steranko says “You got to go away for a few days, I’m doing stuff.” And you were like, “Where am I going to go? I live here.” And you have enough, and you pack up, and you call your friend, and you guys just drive in to the city and go see Howard Chaykin. Is that…?

Groth: Yeah, that’s true. Yeah.

Jim: So, from that moment, and then it’s like, “What do I do now?” But were you already friends with Mike Catron? And he was already enrolled at University of Maryland.

Groth: We were buddies from the time we were about 15, because he was a comics nut and I was a comics nut. And we were the same age, I think we were literally one month apart…

[overlap talk]

Jim: Was he the guy that picked you up from Steranko’s house?

Groth: Yeah, yeah. He drove up from Maryland. He was going to the University of Maryland, and he drove up, he picked me up at Steranko’s, because Steranko told me to go. Now, Steranko told me I had to leave for a few days, so he could paint in an empty house. And so, we drove up to New York… I mean, we had nothing to do so we drove up to New York, and we crashed around a few places. I’m pretty sure that I stayed in Howard’s place one night, he put us up for one night. And we’re up there for a few days, and I can’t… I talked about this with Mike recently, we can’t remember who else we stayed with.

But we banged around New York for a few days. I distinctly remember being in Howard’s small studio, us talking. And of course, Howard again, is like a few years older than me, and old enough to make a difference back then. He was a working professional at the time.

And then we drove back to Steranko’s, and Steranko told me I hadn’t been gone long enough so I’d to leave again.

[01:00:04]

So, then I went down to Mike’s place for a few days, but then when I went back to Steranko’s and I stayed there for another month or so.

Jim: Oh…Okay.

Groth: Yeah, I didn’t leave at that time. I went back and stayed another month, a month and a half or something.

Alex: It’s like Michael Corleone

Groth: Yeah. Exactly.

Jim: Did Bruzenak know Chaykin at that point?

Groth: I don’t think so. I don’t think so.

Jim: So, you knew both of them but they didn’t know each other.

Groth: No, I don’t think they did. No… Ken led a very sheltered life at that time, I think.

Jim: Did he get along with Steranko better than you? Was he able to navigate that better?

Groth: Ken was far more accommodating than I was.

Alex: You said that he was a lot more laid back about it or something.

Groth: He was. He was, he accepted it. And honestly, I accepted it, there wasn’t much I could do… But accept it. But I just knew it wasn’t a good long-term situation; there was tension.

Jim: You were getting more and more politicized at this point, as well. And like me, you were obsessed with Watergate. I was pretending I was sick to stay home to watch the hearings and things. I was crazy about all of that going on.

You were actually a little older so you were in college so you went the University of Maryland where your friend was attending, he was on his second year. You went there for one year.

Groth: I transferred, yeah.

Jim: Yeah… At that point, so you’re there, and Nixon, and DC is imploding. And I read that you actually went to the White House the night that Nixon resigned, to celebrate.

Groth: I don’t think I was there the night he had resigned. I was there a couple of times, at what we called The Nixon Death Watch. There was just a group of hundreds of people, across the street from the White House who had just set up camp. And people would come and people would go, and some people would just stay there for weeks, and I would join them a couple of times. And of course, it was called The Nixon Death Watch because we’re just waiting for him to leave. Unfortunately, I was not there the minute, the day, or the night he left.

But yeah, I was obsessed. We were both obsessed with Watergate. Of, course we were living in Washington so we’re reading The Washington Post every day.

Jim: Were (Bob) Woodward and (Carl) Bernstein an influence? Did they make want to make you explore the reporting angle?

Groth: They made everybody want to be a journalist.

Jim: I was a journalism major too, and that was why.

Groth: Everybody… I mean, it was terrible. The effect they had on journalism schools was terrible. I majored in journalism at the University of Maryland. And yes, I was interested in being a journalist, but we had this huge classes because everybody wanted to be a journalist. Everyone saw the glamour of Woodward and Bernstein.

And of course, I want to think that I want to be a real journalist. But as a result of so many people taking journalism classes, the classes, I thought, were really dumb down. I remember one class assignment was to go home and read the newspaper. I was thinking, that’s like the baseline. I mean, everybody should be doing that anyway.

[chuckle]

And so, I remember being frustrated by what was being taught, and how quickly it was being taught, and I wanted to learn more faster. That’s one of the reasons I dropped out.

Jim: So, you dropped out in 1975, partly because of that. Were you also just over your head busy because of the rock and roll concert?

Groth: Yeah, yeah… Mike and I came up with this idea to put on a rock and roll convention. And I think I dropped out of the university, I think it was either late ’74 or early ’75. I couldn’t keep up with classes.

We started working on this idea in August or September of ’74. And our idea was that, if I put on comic book conventions, so I knew how to put on a convention. I knew the logistics, I knew how to get the hotel, I knew how to get guests, I knew how to put together a dealers’ room. And we can just duplicate the format of a comics convention to a rock and roll convention. And because rock and roll was so much more popular than comics, we would get so many more people and make so much more money. And we would take that money and we will start a publishing company. That was our grand plan.

We really didn’t want to be rock and roll entrepreneurs, we wanted to be publishers.

Advertisement

Alex: Yeah, make money first.

Groth: Right. So, that was our plan. We spent, literally, in almost a year, working on this rock and roll convention. We conceived the idea and we put it all together. I can’t even really begin to describe what that was like. It was just… It started slowly and built, and there was a point where we were working literally 16 to 18 hours a day on this, I mean both of us.

At some point I couldn’t take classes anymore because I wasn’t paying attention to them, and I couldn’t pass them, I couldn’t do the work, And I think we both dropped out, and we put this thing on. It was over the July 4th holiday at a big hotel in downtown Washington DC, in 1975.

[01:05:01]

It came off. We had all the guests, and we had a big dealers’ room. We had a screening room with films, and it was just a complete bust. I mean, we lost more money than we’ve ever seen in our lives.

Alex: Wow. So more than $10,000, was lost.

Groth: Yeah. Well, we lost 15,000… I’ll tell you, we were $15,000 in debt, which at that point in my life, it was like $15,000,000…

Alex: Yeah, specially at that time. That’s a lot.

Groth: I was 19 when we put it on. I guess I was going to turn 20 in September.

Alex: How much was a joint back then

Groth: [chuckle] I don’t know. I never smoked. I don’t know.

Alex: Okay, that’s my unit of measurement, so… No, I’m just kidding.

Jim: But speaking of that, Hunter S. Thompson is part of the story too, so we should talk about that.

Groth: Yeah, we got Hunter S. Thompson to speak there. He was a hero of mine. I loved his work. Reading him kept me alive and kept me sane. I would read him in Rolling Stone, and I read all of his books, but his Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail which I think might be his masterpiece. I thought that was just such a brilliant book, and it was a brilliant take on politics at that time. I wanted to get him…

He was synonymous with rock and roll at that time. He was appearing regularly on Rolling Stones, and he would often reference rock. So, I wanted to get him in there as a kind of political component to the Rock and Roll Expo. I contacted the Rolling Stones lecture bureau, which they had at that time, and cut the deal. We had to pay them up front, to get him to appear. And he did appear.

Alex: Oh, cool.

Groth: It was shaky, we didn’t know if he was going to show up until the last minute. I had to actually go from the convention, get my car, and drive to his hotel, and pick him up. Because somehow, he was having trouble getting to the convention.

Jim: So, would it be fair to say that Mike Catron was more of a Woodward- Bernstein, and you were more of a Hunter S. Thompson, in terms of your approach to journalism?

Groth: It actually would. Yeah, that’s very good.

Jim: Great. All right. So, you did that and you stayed in touch with Thompson to some degree, and that you drove to his house at one point, which is a dangerous thing to do.

Groth: Well, I can’t say I stayed in touch with him, I saw him, after the convention. The convention ended on Sunday, and we were completely demoralized, because we realized we did not, in fact, make our fortune in order to start a publishing company, and had done quite the opposite. We’ve dug ourselves into a huge hole. And so, I think, we were just sort of in shock. The next day, for some reason, I got in touch with the Rolling Stones lecture bureau. And I don’t know why, but I drove down there.

They were in DC and of course, I was in Maryland, but I drove down there for some reason, now I can’t remember why. Hunter Thompson was in the office. And I’d seen him two days earlier, Saturday, I think, and so he knew me. And we started talking, and he had appointments to go to in Washington, throughout the city, and he asked me if I would drive him around, chauffer him around. So, I said, “Fuck, yeah. I’ll do that.”

Alex: Yeah, that’s great.

Groth: So, we got my car and I just drove him around DC. I would drop him off, he’d say, “I’ll be back in about an hour.” And I would do something and then go pick him up and we go somewhere else and, in the meantime, while we’re in the car, we could talk. It was kind of great. I can’t say I really knew him, but I was this kid who was willing to drive around DC, and pay him to appear at my failed convention.

So, Mike and I, in order to pay our rent and to feed ourselves, we decided to go to San Diego that year, which was either in… I don’t know, it was either in late July or early August. Right after the convention we put on. And we decided to go to San Diego and sell comics to make money. It’s the only thing we could do to figure out and make money.

That was when you could call San Diego, a week before the convention and buy a booth. So, we did that, we got a table, and we literally made this decision a week before the convention. We packed up Mike’s station wagon, which was this beat-up station wagon. And we got in it and literally, drove cross country in one drive. Took us 51 hours to drive across the country to San Diego, non-stop… I guess we were going through Colorado, we went to San Diego in the southern route, and I guess that takes us through Colorado, but we thought we were close enough to Woody Creek, which is where Thompson lives so we might as well visit him.

[chuckles]

[01:10:00]

We were still 19 at this time. We thought, “Yeah, that’d be a good idea”, to visit Hunter. He kind of knew us, because we paid him a lot of money and I drove him around DC. So, completely unannounced, because I guess I didn’t have his phone number, but I did have… I don’t know if I had his address, or I just had some sense that he lived in Woody Creek and I’d find him, but we went to Woody Creek, and somebody must have told us that he lived way up the hill, which he writes about. He lived up this long winding road that goes up the mountain.

He lives at the top of this fucking mountain. And we drove all the way up there, got out of the car and knocked on the door. There was a huge peacock in a cage next to the front door. It was the only thing I really remember… Which seemed very Hunter Thompson-ish.

Knocked on the door… In retrospect, that’s crazy because he might have shot us or something.

[chuckles]

But no one answered. He probably wasn’t in there.

Jim: Now, it sounds like the Doonesbury cartoon, I mean the way you described it.

Groth: Yeah.

Alex: Did you take a wiss anywhere around the property?

Groth: We did not have the wherewithal to do that. I remember getting back in the car and going down, and when you’re going down, the cliff was on your right, and I remember that just being a terrifying fucking drive down.

Alex: I have a fear of heights and sharks so… I get that.

Groth: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I have fear of heights too.

Alex: So, yeah, because the music magazine was called Sounds Fine. When you wanted to be a publisher when you put up the rock and roll convention, was that, you wanted to be a music publisher or were you thinking about comics criticism still, at this point?

Groth: No… I don’t know what I was thinking about. I’m not sure I was thinking about anything. I mean, I was scrambling to make ends meet. I didn’t have a job. We owed all this money. I got a job right away, a full-time job, a horrible job because we had to pay back a lot of money. Friends had loaned us money, we had to pay those back. So, I got a full-time job as a designer of a printing company. Mike got a job doing something. And so, we scraped some money together.

But then, I’m just not built, so that I can just go to work every day and come home and live like that. I couldn’t do it. So, the one thing that came out of the rock and roll convention is we get a huge mailing list. We had a mailing list of several thousand people. All presumably rock fans. And a friend of mine who owned a bookstore at the time, told me, he would finance a magazine if we could put it all together.

And so, we created Sounds Fine which was a rock magazine. Now, honestly, I shouldn’t speak for Mike but I don’t think either one of us had that deep an interest in rock. I mean we had a dilatant-ish interest in rock. And really, in all honesty, we were using the rock and roll convention opportunistically to raise money, to establish a publishing company which was what we really wanted to do.

But he said he would finance a rock magazine, so by gad, we were going to put together a rock magazine.

Alex: Yeah. So, that was more, introduced upon you, it sounds like.

Groth: Yeah. But it was part of our passion of publishing. I mean, we wanted to publish. And so, this gave us the opportunity to conceptualize a magazine, to editorially direct it, to solicit articles, essays and reviews. You know who Ted White is?

Alex: No.

Groth: A science fiction author who’s also a comics fan. He lived in… I think he lived in Arlington, Virginia, so he was sort of a neighbor. He was also older than us, but he was a comics fan and a science fiction author, so our interests intersected. And he was also an enormous music fan and critic. And so, we enlisted him to write a big column. It was a column on, basically, avant-garde rock music.

Alex: Oh, wow. That’s a cool combination of perspective in one person to write an article like that.

Groth: Yeah. And Ted knew his shit. I didn’t know any of it. But Ted, really had a great grasp of what was going on in the avant-garde of rock music that time. We just trusted him because we couldn’t assess it. But he would write these enormous fucking columns, he was like a machine. He wrote these columns that must have been, five, six, seven, eight thousand-word columns, and we just let him go.

We thought we were doing some good. We thought, “Well, if we’re going to do this rock magazine, let’s introduce people to Mott the Hoople, or whatever the hell he was writing about.” We’d also have articles about Dylan, and the Beatles, and the Stones… But it gave us the opportunity to employ these skills that we loved using… That I honed doing the fanzine… We used comic artists to do covers for Sounds Fine. David Mazzucchelli did one. Yeah, a number of cartoonists would go on to…

Alex: How many issues were there of Sounds Fine?

Groth: 26?… Something like that.

[01:15:00]

Alex: Yeah, so that’s a pretty good chapter in your life right there.

Groth: Yeah, I mean, it was, we would do it, it would come out… I think it was monthly. And we would crank it out and we were excited to do it. Never made any goddamn money. I don’t know if Mike and I actually made money on it. I don’t think so. I think our investor just kind of broke even and he invested the money occasionally. But we were excited to do it. It gave me the opportunity to write movie reviews.

Alex: There you go. Finally.

Groth: Since it was our magazine, we could do whatever we wanted. I could write reviews of movies in it. I remember writing a review of… It’s a Kubrick film, Barry Lyndon.

Alex: Oh, I love that. A lot of people don’t like it but I love that movie.

Groth: Well, my review’s very positive. I’ve never seen it since but I remember loving it.

[chuckle]

So, yes, it was great just doing that. We set up a place. I had a two-bedroom apartment. I think we had one bedroom that was set up as a kind of a studio, where we could put up the magazine; kind of honing our skills.

And then in 1976, we started publishing The Journal. But we actually put out both of those at the same time, for a while.

Alex: Oh, ok. So, they actually were side by side, at one point.

Groth: Yeah.

Alex: So, you guys purchased the rights to The New Nostalgia Journal or Nostalgia Journal. How’d that come about as far as… Did you pay for that?

Groth: No, purchase is putting a spin on it, they basically gave it to us.

Alex: Okay. They just didn’t want to do that anymore.

Groth: No, they were burned out. We approached them, because we could see that they were burned out. And they were competing with The Buyers Guide, and we thought we could do a better job. And we thought we could infuse it with some fresh, young blood, and we offered to take it over. And they were really only too happy to give it to us.

Alex: That’s what Paul Levitz said about his fanzine. He said the same thing, they just kind of… It wasn’t really a purchase; it was just kind of passed over…

Groth: The Comic Reader.,,, Yeah. They were tired. They were burned out. They were tired of fighting. It was one slog for them because they were competing with Alan Light and The Buyers Guide. And Light was using all of these underhanded tactics to undermine them, and sabotage them. We thought we could withstand all of that, and make a go of it. Which we didn’t really because we turned it from an advertising-based periodical to a more content driven periodical…