Comic Book Historians

As featured on LEGO.com, Marvel.com, Slugfest, NPR, Wall Street Journal and the Today Show, host & series producer Alex Grand, author of the best seller, Understanding Superhero Comic Books (with various co-hosts Bill Field, David Armstrong, N. Scott Robinson, Ph.D., Jim Thompson) and guests engage in a Journalistic Comic Book Historical discussion between professionals, historians and scholars in determining what happened and when in comics, from strips and pulps to the platinum age comic book, through golden, silver, bronze and then toward modern

Support us at https://www.patreon.com/comicbookhistorians.

Read Alex Grand's Understanding Superhero Comic Books published by McFarland & Company here at: https://a.co/d/2PlsODN

Series directed, produced & edited by Alex Grand

All episodes ©Comic Book Historians LLC.

Comic Book Historians

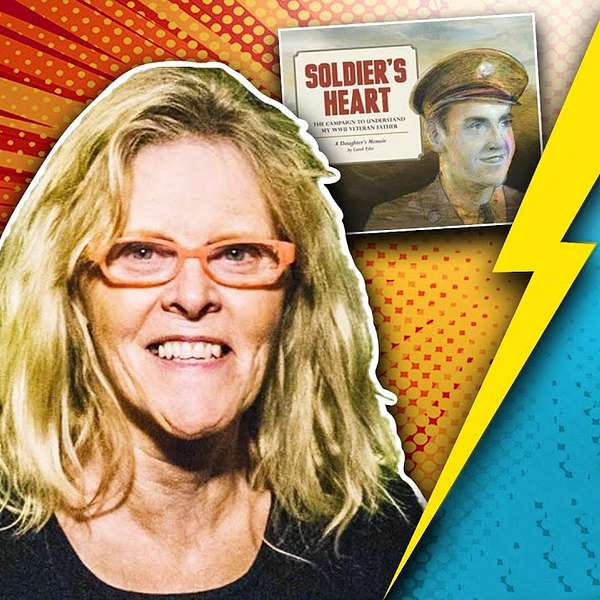

Carol Tyler: Comic Writer & Artist Interview Part 2 by Alex Grand & Jim Thompson

Alex Grand and co-host Jim Thompson interview painter, autobiographical comics pioneer and 11-time Eisner nominee Carol Tyler, author of Soldier's Heart: The Campaign to Understand My WWII Veteran Father: A Daughter's Memoir (You'll Never Know), Fab4 Mania, and Late Bloomer in the second of a two parter. We cover her early work for Weirdo, Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sister to her current project, as well as her marriage to Justin Green (Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary), her friendship with the Crumbs, the controversy over her accepting the first Dori Seda Memorial Award, Leonardo DiCaprio’s babysitting skills and her life’s most tragic losses and greatest triumphs. Part 2 of 2. Edited & Produced by Alex Grand.

#Beatles #CarolTyler #Eisner

©Comic Book Historians 2020

Jim Thompson:

You mentioned a Diane. I just want to clarify that’s Diane Noomin, correct?

Carol Tyler:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Jim Thompson:

Okay.

Carol Tyler:

I love these … I love them all. I love Diane. I love Aline. I love Trina.

Jim Thompson:

Okay. Well, I wanted to get in to that a little bit, that-

Alex Grand:

Actually, a quick question I have. Were the fights fueled by alcohol or cocaine?

Carol Tyler:

The underground stuff was booze and pot.

Alex Grand:

Booze and pot. Okay. There you go. All right.

Carol Tyler:

Cocaine does not make you fight.

Alex Grand:

Yeah. Okay. There you go. So it was more of the booze and the pot mixed. Some comics, some rock and roll.

Carol Tyler:

And jealousy.

Alex Grand:

Jealousy, sexual.

Carol Tyler:

Bravado.

Alex Grand:

Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

You know, “I’ll show you.”

Alex Grand:

Okay.

Carol Tyler:

Shit like that. And then, with the women it would be just snarking and all that stuff. I’d be like “Oh, stop. I don’t want no fights!”

Alex Grand:

Right, right. That’s cool.

Jim Thompson:

So I wanted to, before we get to Wimmen’s Comix, I want to ask just a few things on Weirdo, about the end of it. What was happening there at the end? I mean, it was such a great moment in comics, and with Aline it was bringing in all of these women artists. I mean, it was a huge moment. What was the downfall? Was it just not not enough readers or what was closing? Or were there personality clashes, or what was bringing it to an end?

Carol Tyler:

I think, no. I don’t think it was personality. I think you had your east coast, west coast thing going for a while there. Raw magazine and Weirdo over here. And by then Bijou and Arcade and all those things were winding down, pretty much gone. And then the Crumbs moved to France. That changed things a little bit. That was like a kind of an end of an era when they left.

Carol Tyler:

Head shops closed. A lot of places where you’d go get these things had closed. And they started to go to bookstores. And then there was a big problem because you’d be in the bookstore, you’d ask for the comic section, you’d end up seeing all the super stuff, and it’d be very few, if any, things like Raw or Crumb’s Weirdo in a place like Barnes & Noble. So where do you get that stuff? You know, distribution … It just petered out.

Jim Thompson:

Now you were talking about trying to figure out how to make the black and white, and the line work. You even talked about wind and things. Were each of you, all the artists there, learning from each other or adapting? Because like everybody had different approaches to it. I mean, like Mary Fleener bringing in all of the cubism and things, and Julie, you say, doing the stuff she was doing and the fluidity of her stuff. Were you guys learning from each other, or was it just finding it within yourself?

Carol Tyler:

You know, I can’t speak for others, but I was very, very acutely aware of the fact that I did not want to look like I was taking anybody else’s stuff. So I would read people’s comics, but at the same time, I had a slight aversion because I didn’t want to inadvertently … But it takes a lot to try to translate your marks, and find what works for you. Can you imagine if I started doing cubism stuff on my pages? Be like “Why is she copying Mary Fleener?”

Jim Thompson:

You couldn’t do it-

Carol Tyler:

And while that’s-

Jim Thompson:

Once she got there, there was no way you could do that, even if you wanted to.

Carol Tyler:

Why would I even try? So you find your own mark, your own way of putting it out and you got to know there’s no … I don’t know. Mary lives in LA somewhere. Maybe? Julie was up in Canada. We didn’t get together. The only person’s work I saw up close was Aline’s, because she was my neighbor, but I didn’t draw like her. And I know she wasn’t ripping off of me. She had found her own thing. I guess what I’m saying is, it’s not like college where we all living in the same, or your studios are in the same building or something like that. You work in isolation at wherever you’re at, and you show up with the work or you send it in, or something like that.

Carol Tyler:

I do know there was a couple of times when I would show up in Winters with my pages, and it’d be like “Ooh, I misspelled a word,” or I forgot something and I’d have to sit down at Robert’s drawing table, pick up one of his pens and make my corrections right there. It didn’t seem like I was at the altar of Holy or anything. It was just a drawing table, handy, that I needed in order to get that change corrected. Because there’s no Photoshop. So that means getting the white out and fixing the board?

Carol Tyler:

Seems like “What? You sat down and crumbs?” today, but-

Carol Tyler:

… like, “What? You sat down at Crumb’s today?” It’s like, “No big deal. It was just something I had to do.”

Jim Thompson:

That’s a good point, in terms of printing, now you were coming from a art background where you had seen your things on display as you intended them to look during the printing process. How frustrating was it in those early days to do the work and then see what it looked like on paper?

Carol Tyler:

I had a hard time because I’m very aware of the texture of the paper and if you put on Wite-Out, then you put another blob of it on, if you put too much globs of Wite-Out, you’ve got a mountain. Which, when printed, may show a little ghosting or something like that, so now you’re getting shades I didn’t intend. So I had a lot of … It was a big steep learning curve for me to figure out what I could get away with, what to do, and what not to do when it came to translating marks and getting thing printed.

Carol Tyler:

I look at the work, side-by-side comparison of the originals to the printed today, and it’s appalling to me, because I know what I was doing. I was more interested in the shapes and the textures, you know, that, but it’s a flat page, people. It took me a long time to say … And now with Photoshop, hey, it’s great. If I misspell a word or I got something wrong, I’ll just put it down here in the margin and slip it in later. I don’t have to make a patch with an X-Acto knife, and tape it from the back, and make sure it’s clean. I was appalled, because I didn’t like the way I was throwing down the marks, the way they were translating, which would look great in oil paint, but it’s black and white. It took me a while.

Carol Tyler:

I’m still, like I said, I’m still working on, sorry, learning things. When to stop. I kept trying to figure out … There’s something on my … I kept trying to figure out, like, okay. My students have trouble with this, too. So you got this jaw, there’s no line, really, or the nose. What you have are various shadings, but if you don’t shade it with the right size of a crosshatch, it’s going to look like you’ve lines on your neck or pieces of lumber. It was all over the place when I started. I go back and I look and it’s like, “Sheesh, clean that up, clean it off.” But I was trying to make a color in my mind and it was coming out logs.

Jim Thompson:

Yeah, no. We’ve talked to some inkers where they’re coming from a painting background and they want to paint and they have to figure out inking techniques to do that. It’s very hard.

Carol Tyler:

Really hard.

Jim Thompson:

So what is the different between Weirdo and Wimmen’s Comix in your work? Like when you started doing those, were the stories different, or was it just a different comic and you were doing your work and it didn’t make any difference?

Carol Tyler:

Really, the only thing I could think of was there was themes with Wimmen’s, there was a theme. So it’d be like, “The theme is disastrous relationships.” Okay, I can tell a story about that.

Jim Thompson:

Sure.

Carol Tyler:

What story would I do? Then I’d think, well, the first you think about is the breakup with so-and-so. It’s like, “I don’t want to do that. Push past that a little Tyler, can you remember something disastrous that happened to somebody else?” And that’s when I remembered my roommate who was South Korean.

Jim Thompson:

Right. So that was your roommate? I see.

Carol Tyler:

And so, I mean, I could have picked a hundred stories about my own disastrous relationships, but I thought, “Let’s see if we can focus on somebody else.”

Alex Grand:

That was actually a good focus, because I found myself engaged in that one, wondering, “What’s going to happen next with this relationship?” That was really well executed.

Jim Thompson:

So when Wimmen’s Comix gets a new publisher for issues 11 through 13, and they’re doing it through Renegade Press. Did you know Deni Loubert?

Carol Tyler:

No. I was-

Jim Thompson:

I’m sorry.

Carol Tyler:

I wasn’t part of the collective.

Jim Thompson:

So you were just submitting work and it didn’t really matter who was publishing it?

Carol Tyler:

I think I was on a list. They’d send me a thing and say, “Hey, you want to contribute?” Be like, “Sure.” And I didn’t pay any attention to who was who. It’s like, “Oh, here’s another gig.” Because I was looking, I really wanted to make a living at it, and it was hard to because the rates were so bad. And I knew I was learning, and I was new to the party. So I was doing what I could to stay humble, and try to understand how I could tell comics, and tell a good story and all of that. Oh, here’s another. Okay, I’ll do one for them. Here’s a special one-off, Fantagraphics is doing. Okay, I’ll do that.

Jim Thompson:

Was there something different about being involved in Wimmen’s Comix because of the history of it? It was just another job just like Weirdo for you?

Carol Tyler:

I hate to say that. I didn’t know there was a mission, you know? Is there a mission? Oh, to be a part of Wimmen’s means something? No, to be a part of Wimmen’s meant, “Well, I get to have a story published with a bunch of other awesome cartoonists.”

Jim Thompson:

Is this when you met Trina or did you already know her?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, I think I must have met her through Turner, because she and Ron were very good friends. I think he published a lot of … Or helped her in her beginnings. But he adored her, and she was wonderful and always kind to me. Trina was kind to me, Aline was kind to me, everybody in that comics community was so welcoming and so kind. I just felt wonderful, you know? I was very sensitive about not wanting to be perceived just as Justin Green’s wife, “Let’s give her a job because she’s married to Justin.” I didn’t want that. I wanted my own merit. And so I made that clear with people, I don’t want you to say, “Oh, we want you to be in this because we like Justin.” I want you to do it because you like my work.

Jim Thompson:

Trina has often talked about the sexism of the early underground stuff. Did you encounter that, or was it not as pronounced by then, or it just wasn’t something you were thinking about?

Carol Tyler:

I’m aware of it now, but at the time I remember saying to her, “I don’t get what you’re talking about. I don’t feel that.”

Jim Thompson:

That’s interesting.

Carol Tyler:

“Whatever I want to publish …” Look, we had Aline there … Check on this quick. We had Aline as the editor, she was in for the work, so there was that. But, I’ll tell you, something happened at one of these shows I was at recently, I can’t remember if it was [SVX 01:47:29] or at Comic-Con. But I was at a panel with a bunch of guys, maybe it was Weirdo, I don’t remember. But I was on a panel with a bunch of guys, we were talking about the old days, and they were like, “Ha, ha, ha, remember how we used to make $100 a page?” And I said, “$100 a page? I was in that issue, I only got paid $35.” And they were like … I am thinking, “Trina was right!”

Jim Thompson:

Do you think that was actually at the Weirdo panel in San Diego? That that’s where they-

Advertisement

Carol Tyler:

No, I don’t think it was. But it was something so revealing to me, that these guys were all laughing about the low page rate, maybe it was 75 bucks. And I know I was making $35. So it’s like, “Fuck, they were paying the men more than me? Is that true?” You know what a difference that would have made if I had been able to make that same page? It seems like nothing today, but back then you’re spending 20 to 30 hours on a page. And I remember saying like, “Aline wants a four pager, I wonder if I made it a five page, that’s an extra …” I think I was getting 50 bucks, maybe $75.

Alex Grand:

And I think page rates should be the same, but do you think that was a gender thing, or was it more like someone had more of a reputation, people wanted to see their stuff more at that moment in time? Was there a seniority issue there, or was it really a gender difference?

Carol Tyler:

It was all the above, because there was times it’d make me so damn mad. I would do a really good story, and then there’d be the names of the people contributing on cover, “And more. And more.” That was my name, I guess, “And more.” So how are you ever going to get looked at, how are you ever going to be recognized, how are you going to get up there if you don’t get put on the cover? If they don’t champion your work, if they don’t get behind you? If they don’t pay you? Because when you’re working for shit wages like that, a little bit of money, then you have to go get second job, and a third job, you can’t put your full attention to things.

Carol Tyler:

If somebody had said to me, “I love you so much and I love your work so much, I’m going to throw some money at you.” I would have said, “Thank you.” I could buy childcare and I can produce 10 pages. And they’ll be like … I can do this, because guess what happened? The minute my kid got in college, I did Soldier’s Heart.

Jim Thompson:

Yeah, and I can’t wait to get to that, because that’s the thing. I mean, that’s something. Super quick, just because people are going to want to know, tell us who your babysitter was back in the early days.

Carol Tyler:

Leonardo DiCaprio, Leo.

Jim Thompson:

Yep, and that’s because his father was a comic book guy and knew Justin. They had done some work together, and he was around, and he was good with kids, right?

Carol Tyler:

George and, I think, Justin did some illustrations for him. I couldn’t get a sitter, so I had to bring the kid with me. I was like, “I have to bring the kid to the party.” And they were like, “Don’t worry about it. We’ve got childcare.” It Ron’s son, Colin, and his friend, Leo. She was like, “Mommy.” Get her out of here, okay. So I can schmooze and be with people, and then I went … I thought, “I’m going to go check on my kid.” So I went in there and looked, and they were … Leo was tickling her on the bed. It was so cute. [crosstalk 01:51:41].

Jim Thompson:

How old was he at that point?

Carol Tyler:

Oh, god. Okay, he must have been like … How old is this guy? How old is he now?

Jim Thompson:

Oh, I don’t know. He’s-

Carol Tyler:

They were a little older, they were like 10 years old or something, maybe.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, so this is before he was on Growing Pains.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, because he’s 46. He was born in [crosstalk 01:52:06]-

Jim Thompson:

She later had his poster up from Titanic.

Carol Tyler:

My daughter’s 35 now.

Alex Grand:

He was born in ’74, so he was probably, yeah-

Carol Tyler:

11.

Alex Grand:

… maybe 14 or 12, or even earlier before-

Carol Tyler:

12, 13.

Alex Grand:

When was your daughter born exactly?

Carol Tyler:

’85.

Alex Grand:

’85. So he was probably 12, yeah. There you go.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah. So they were like playing video games and being like goofy guys, but then they were jumping on the bed the next time I checked. She was laughing her ass off. So they did a great [crosstalk 01:52:32]-

Alex Grand:

That’s awesome. And then we talked about George DiCaprio when we interviewed Bill Stout. They had some involvement together as well. It’s pretty cool.

Jim Thompson:

And what other celebrity connection is … And I don’t know if it’s true or not, is William Friedkin a cousin from your husband?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, first cousin.

Jim Thompson:

Do you know him?

Carol Tyler:

Although [inaudible 01:52:54] does not like to discuss this. He has distanced himself from Justin for reasons that we do not understand nor care about anymore. So it’s like, “Fine, you want to be like that? Stupid.” And let’s see, what other claim to fame do I have? I mean, people say, “I know you.” They say that about me. My students, it’s like, “Oh, I’m a celeb? Whoo. That’s so cool.”

Carol Tyler:

No, he’s the biggest thing, I think, Leo. But I wanted so much for him to … When she was going through her bad time, when she was 12, I wanted so much for Leo to show up and cheer her up, but it didn’t happen. Although she got a lot of mileage out of that, she had started at a new school and walked in, and they were like, “Who are you?” And she said, “That doesn’t matter, but Leonardo DiCaprio was my babysitter.”

Jim Thompson:

That had to get her right up there.

Carol Tyler:

After that she was … cool.

Jim Thompson:

All right, Alex is going to talk about Late Bloomer and the stories that go in it.

Carol Tyler:

All right.

Alex Grand:

You had worked on Wimmen’s Comix and in through the ’90s, there was Twisted Sisters with Kitchen Sink. And a lot of this stuff was collected in 2005 in Late Bloomer. Fantagraphics did it, it was a reprint, but there was also some unpublished work. Robert Crumb said in the forward that, and I’m going to quote him here, it says that your stories are, “All about gritty reality. The hard struggles of common, everyday life, no escapism, no cutesying. She never tries to make herself come off as Miss Cool and Clever. Nothing gets contrived or overdramatized, the level of honesty about herself is shocking at times you’ll see, but it’s the kind of revelation that uplifts and instructs.” So is that how you see your own work? Is that what you’re aiming for when you’re doing that? Is there a consciousness to it or is really an artistic subconscious effort to get energy out creatively? Tell us about that process a bit.

Carol Tyler:

So what Late Bloomers is is a collection of pretty much the stuff I did for Weirdo, and Wimmen’s, and some other random one-off that were out there. And so the reason for doing them is just that I always wanted to tell a story. I wanted it to be a good story, something worth reading. Pretty simple like that. And people can read and interpret, but in order to tell a good story, you have to be honest. So you can’t shy away from difficult truths, or lie to your audience. All that stuff shows through. It seems funky or wrong.

Alex Grand:

Right, it doesn’t fit.

Carol Tyler:

No, it doesn’t fit. So my work does have an authenticity, it’s because I tell you what’s going on. I’m going to tell you what happened or what that thing was, or what I felt, or what I encountered.

Alex Grand:

One of my favorite ones from there is a 1991 story you did, Adult Children of Plumbers and Pipefitters, and it was this plumber’s daughter who worked in a corporation and was very talented. But she was very foul-mouthed and practical, fixing people’s pipes in the office, that was funny. And how much of that do you feel like you’ve … Because your dad was a plumber that almost you come off this way to some people, too, yourself?

Carol Tyler:

I was actually working in an office, in a history center, and there was a lady there who was in a codependency group. I was like, “What’s that?” And then she would talk about her … She’d have to go hug her little teddy bear in her office and be like, “That is so weird.” And then she’d talk about codependency, codependency. She was an adult child of an alcoholic, it was the thing at the time. And I thought, “Well, I’m the adult child of a pipefitter. I wonder how that would be.”

Carol Tyler:

So I just imagined, you know, this lady on her way to a meeting with the shoulder pads and the whole bit, with the hair and nails, and having to go to the meeting. And yet, notices in the break room, notices a drip. “Ooh, that could cost money,” because she knows [crosstalk 01:57:35]-

Alex Grand:

Right. She knows what’s involved, yeah.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, so she starts tinkering with it and it becomes a full-blown problem. And they’re like … I was thinking about that the other day, because the office, the main guy’s name is Mr. Greedy, “You tell Mr. Greedy I’ll be up in a minute.” So she gets involved and fixes the drain, she’s cussing like a plumber, because that’s what they do. “You cocksucking son of a bitch [inaudible 01:58:05] goddammit fuck.” You know, she’s a lady with a puffy bow right here, ready for her meeting.

Alex Grand:

Right, right.

Carol Tyler:

And so, she, “Tell Mr. Greedy I’m saving him thousands of dollars on plumbing bills. He can wait.”

Alex Grand:

It’s a big deal, yeah.

Carol Tyler:

And then she’s in her codependency meeting later with her teddy bear, and she’s talking about he doesn’t appreciate what she did for him, basically. So it was straight out of what this lady was talking about all the time, about her codependency group. And I thought, “Okay, adult children of alcoholic, well I’m an adult child of a plumber, and this is how it would go down.”

Alex Grand:

Okay, there you go, yeah. So then, now in ’93 you had a story, Migrant Mother, and this was interesting because you lived in Sacramento in 1986. And this is all about being a new mom again, traveling to Colorado, it was hell. Something about permanent damage to the right ear, so that sounds like a tough … That all happened?

Carol Tyler:

It all happened. I went out there, my husband had one of these miraculous gigs where he made $25,000 in six weeks. It was a fluke. So we were like in the money. He was ecstatic. And I got a cold while I was there. I started to feel bad, shitty, really sick. It goes through that in the story. It talks about how I feel so terrible, but I just get this thought in my head, because my kid was terrible twos at the time. I just got to go home. Because my home, I fixed the house, there’s basically a giant rubber room. She couldn’t hit her head on a coffee table, because we didn’t have one. It was just a piece of carpeting and pillows. There’s nothing, very simple.

Carol Tyler:

So just go home. I couldn’t get home, because I had terrible ear. They stop in Phoenix, then they were going to go home. I couldn’t make it out of Phoenix, like terrible. It felt like, honestly, up in there … Putting things, it was like chopsticks they were sticking up into my head.

Alex Grand:

Right into that frontal sinus, yeah.

Carol Tyler:

Oh, it was the most painful. Don’t ever get on a plane with a cold, because as they descended, I couldn’t relieve the pressure, and it was pushing. I was trapped. I thought I was going to have a stroke. I thought I was going to explode and I had a terrible kid. Everything wrong. I sent the baggage ahead. I had no cash on me. It wouldn’t happen today, but back then, it was an absolute disaster. She was a hell on wheels in the airport.

Alex Grand:

This sounds hard. I feel like I did that to my mom, I’m sure. I feel like maybe my mom repeats something like that.

Carol Tyler:

Every kid does it. Yeah, every kid acts terrible at that age. But to be sick and stranded, it was just awful. People like that story. I’ve heard over the year about they can to relate to that, especially have their terrible kids, you know? Terrible [inaudible 02:01:37] we call it.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, I feel like I did stuff. I think one time Mom took me to Marshalls, and then I actually went and hid in one of those clothes carousels for like five hours. And she thought I was kidnapped, she had the cops come.

Carol Tyler:

Oh, what were you doing? [crosstalk 02:01:54]-

Alex Grand:

And then I just stayed there, I stayed there and I tortured her. And I knew what I was doing. I think I was five at the time. And she still brings it up now, and I finally got out, “Ta-Da.” And she was like, “That’s not funny.” I mean, it was … I feel bad looking back.

Carol Tyler:

[inaudible 02:02:07] I think it’s funny, Mom, come on.

Alex Grand:

And I feel like you were kind of tortured in a similar circumstance. In 1995, and you talked, you mentioned the Hannah story, about your late sister, Anne, that you found out more about. In 1969, you were 18 and that’s when you found out about Anne, right? When you were 18?

Carol Tyler:

I think I was 17, you know why? Because I am a late in the year birthday.

Alex Grand:

Okay, there you go.

Carol Tyler:

It doesn’t matter.

Alex Grand:

I know what you mean. I’m one of those, too. Yeah, you’re right. Okay.

Carol Tyler:

I didn’t hear about Anne until I was in my … 1993, 2, or 3, so I was 40s?

Alex Grand:

Okay, so although you found out about Anne at 18, you got the details later?

Carol Tyler:

Well, I knew my whole life, I knew about Anne. Like I said, she was the star at night, and I also knew we had her, because I saw her pictures.

Alex Grand:

So even as a kid your mom would make a reference to her?

Carol Tyler:

Very simply that she was in the photographs and not to think about it, just … And every now and then she’d just crying about something that had to do with Anne and that would be it.

Alex Grand:

And that was it. And that was done in Drawn & Quarterly One in 1994, you were nominated for a 1995 Eisner Award and it’s on the Fantagraphics list of Top 100 Comics of the 20th Century. So this struck a chord with a lot of readers including myself when I first read it. I’ve never had that happen to me, but I can easily see that happening to any parent or any family. What do you think it is about that story that … About your story with that, that connects so many people when they all read that?

Carol Tyler:

I don’t know, because I started to realize I was connecting at a certain point. And yet I didn’t want to feel like, “Oh, this is my job to connect with these emotionally gripping stories because I only had one sister that died.” And I thought … I was so happy that I was time tripping with it, showing older era or I could do before. Like looking back at ago and today, and translating visually. I was looking at the formal aspects of conveying the idea, but I don’t really … When I did Hannah, I’d worked at that history place for five years, and I got laid off, and I banged it out in like a few months. So it was pent up.

Alex Grand:

Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

I kept doing Weirdo stories and I had to stop or cut back a lot because I was working at this history place. And that’s during that time when my mom told me. So the first chance I got, that’s the story I did. I remember Chris Oliveros saying afterwards, “Do you think you could do another one like that for our next issue?” It was like, “No.”

Alex Grand:

Right, we need more of that. Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

I can’t. And then I wanted to … You can’t overanalyze things or you’ll kill it. What, you okay?

Alex Grand:

There was something about, also, you made mention of abduction of 12-year-old Polly Klaas, is that right? And that had some connection?

Carol Tyler:

Yes. Yeah, because during the whole time in California, this was one of the most gut-wrenching abduction of a child. It was live television. So back before the way the media is today, you can get on your thing and look up anything at any time. So you’re sitting there watching TV, you know, you see the Challenger explode. You’re watching TV, all of a sudden there is live coverage from Santa Rosa about this girl who was stolen out of bedroom. It was horrible. Or the kid gets stuck in the drainpipe. That was an experience that we really don’t have today that comes upon you like that. “Oh, this is a shock.”

Carol Tyler:

And so the whole time I was doing that, yeah, the Polly Klaas drama was unfolding. And then, they had her funeral live. It was so sad. It got to me. So I put that emotion into the piece, you know?

Alex Grand:

Into Hannah, right. Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

I mean, it wasn’t because of that, but that’s where I was at. When I was doing … I knew I was like, “Okay, now I …” With anything that you’re doing that’s emotional, you have to hit the content. But when I did that Hannah story, I had also done all this research into like, “Wait a minute, Ravenswood Hospital, are they still in business?”

Alex Grand:

And so you look into the hospital where Anne died.

Carol Tyler:

The old-fashioned way, I had to look things up and make phone calls. And so when I found out that she died because the hospital had fucked up, I called the hospital to get her records. And one lady says, “Oh, yeah. Okay, we got them right here.” I said, “Oh, great. Okay, because I want them. Send them to me here.” “Well, okay. Call back tomorrow.” “Fine, I will.”

Carol Tyler:

I call back and I get this, “We’ll transfer you to this other lady.” So I get this other lady, she says, “Oh, hi. So you’re the sister of a long-deceased Anne Tyler? Oh, I understand that you have a desire to contribute to a fund to have a memorial fountain built in her …” I said, “What? No.” She honestly thought I was calling Ravenswood Hospital, this lady, to donate money so they could build a memorial fountain to her. I said, “Where did you get that idea? I want my sister’s records. I want to know exactly, according to you guys, what happened. I know what happened.” Well, I kept not hearing, not hearing, not hearing. A couple of weeks later I call back and they said, “Oh, there’s no records.” They had conveniently had lost them.

Alex Grand:

Yeah. That had happened around the time you were putting that story together? That happened in the ’90s, this situation with the records?

Carol Tyler:

Because my mom didn’t want anything to do with it, I was like, “Mom, you could still sue.” She was like, “Leave it alone.” So when I was drawing the Hannah story, and there’s that place where she’s got the burns. I draw a line and there’s like smeared … The red ink is smeared, that’s because I was crying when I was drawing it, and I was taking a tissue and dabbing, because I didn’t want to get it on the page. But it hit the red line and made all the smear marks that were her burns.

Jim Thompson:

Oh, wow.

Alex Grand:

So then the mechanism of death, just from what I read, was that she had burnt herself. I think your mom was preparing something on the oven, it poured on her, burned her. She went to the hospital, stayed in overnight-

Carol Tyler:

Oh, wait. Stop.

Alex Grand:

Okay.

Carol Tyler:

There’s no ambulance. There’s no 911. So you’re screaming out the window, while you’re hanging your kid, “Help! Help!”

Alex Grand:

Right. Yes.

Carol Tyler:

So a neighbor drives her to the place. They say, “She’ll be fine. We’ve bandaged her up. Go home. We’ll see you tomorrow morning.” Because there’s no phone. My mom and dad didn’t have a phone yet.

Alex Grand:

Right, right.

Carol Tyler:

So when they came in the next morning with their [inaudible 02:10:14] to pick up their child, a clerk at the front desk says, “Oh, she’s listed as deceased.”

Alex Grand:

Right. So she slept on her back, vomited, and choked on it, right?

Carol Tyler:

They gave her some kind of medicine.

Alex Grand:

Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

They gave her medicine, it made her choke, and because they had her on her back, she aspirated.

Alex Grand:

Okay. There you go.

Carol Tyler:

And today you sue the hell out of somebody like that. But my mom said, and I said it in the strip, and she’s always maintained that would have been no good money. It would never have brought us to any kind of goodness or happiness. She’s right.

Advertisement

Alex Grand:

Right. Revenge money, in a way. So, yeah. It’s hard to put … Money and justice, how that’s a complicated, complex question.

Carol Tyler:

And there are people who would say, “Take the money.” She did not, till the day she died, she didn’t want to discuss it, anything. She thought it was her fault.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, that’s interesting. Because now the next topic is Zero Zero #4, 1995, about licking a dog’s butt. That’s quite a different topic than what we were just talking about. But you did create more things, you did go over more stories. One was really interesting, the-

Carol Tyler:

Part of that is I like … I would, every now and then, I would say, “It’s comics, why don’t you make something kind of funny.”

Alex Grand:

There you go. That’s what that is, it’s a departure from the serious. The Night I Rode the Hard Drive to Heartbreak, 1996, The Computer Matching and a Terrible Night at the Dance, this was printed in Mind Riot: Coming of Age in Comix. So that’s interesting-

Alex Grand:

… coming of age in comics. So that’s interesting, so this was in your high school, that they had a computer match with your-

Carol Tyler:

Yeah.

Alex Grand:

… And this was what? In the late ’60s, they were doing that?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, that was a theme comic. It had to be about new technology and stuff. That was the theme. So I thought about that computer dance and we’d have these cards. I was looking for some, we’ve had these IBM cards and we’d have to fill in the circles of what our ideal may look like or our ideal. Yeah. So then they matched us with the public school kids. That was the mistake.

Alex Grand:

Don’t let the Catholic kids integrate with them.

Carol Tyler:

Uh-uh (negative). And so yeah, the story goes on to talk about how I get Mr. Gorgeous, but he’s not interested in me. I’m all dolled up working class style, with the wrong clothes and I’m not willing to do what he wants to do. So I barked at him like a dog.

Alex Grand:

That’s a good reaction.

Carol Tyler:

He called me a dog, so I caught him in the parking lot. You’re terrible.

Alex Grand:

And you actually did that?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, I do that. My stories are not fiction.

Alex Grand:

That’s amazing, I think. That’s funny. 2002, the substitute teacher at Arizona Elementary wanting to survive the parking lot, but it turned into a sad discussion of the mental illness of the young Romero who killed herself. That was an interesting one because it kind of starts off comical, but then it becomes this really sad thing. And that’s an interesting, almost bittersweet story, right?

Carol Tyler:

Well, because isn’t that the way it is with children? And I’m talking about my experiences as a sub, which anybody who’s been a substitute teacher knows you’ve got a million stories and you have to be adaptable and you have to make it up on the fly half the time. And I really kind of covered the topics of the situations I would roll into. And then yeah, the most shocking was it was when this incident with this girl, who over the weekend hung herself, and they have to go back to that same school and find out about it.

Alex Grand:

Right. And no one called you, no one told you, “Hey, that person that you connected with did that.”

Carol Tyler:

Tell the sub, just the sub lady. That was hard.

Alex Grand:

So 2002, and in the end, you work your daughter into the comic, and she’s older, and she understands comics now, she’s coauthor in it. So this is an interesting evolution her being the toddler that was torturing you on a flight. And now it’s like, she’s in the comics with you. So tell us about that and kind of seeing her grow up and being a coauthor in some of this stuff.

Carol Tyler:

Well, in Late Bloomer, I set it up into three sections. So the first section you’ll see a picture of her as a little baby. On the first part of the first section, there’s a image of her in the yard and she’s on the little blanket I have down. She’s cute. I’ve got her little things on the clothesline. And then the chapter head for the second chapter shows kind of our kid crap backyard. And she’s like 10. And things are a little bit more disarray. And I think I show the metaphor for myself on the first one. There’s a chair, a drawing table chair, and it’s in pretty good shape, a little bit worn.

Carol Tyler:

And by the third one, there’s a tiny little bikini of hers on the clothesline. Those are her clothes as they go along. The baby clothes, there’s a bunch of them. When she’s 10, there’s a few less. And then her little bikini, and she’s in a lawn chair, and my drawing table chairs like this. So I show the evolution of her physically for the chapter heads, for the content, from each of the sections. Yeah. So by the time she gets to a certain age, yeah. She knows that mommy’s going to tell a story about me. “Right, Mom?”

Alex Grand:

Mommy always talks about me. Yeah.

Carol Tyler:

Well, at a certain point, she knew kind of early on. I love this story. When she went to kindergarten, she came back home and she said, “Mom, guess what? Mommy, Jason’s dad, he works at a bank.” I’d say, “Okay.” And then I though, “Wonder what that’s about.” It’s like, because every adult she knows is a cartoonist. And here, she met a kid whose parent is something normal and she was shocked by it.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, that’s right. Culture shock.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah. So she was aware that she was in the comics. And over the years I’ve explained to her and apologized and all that stuff. And she said, “I don’t care.”

Alex Grand:

2005, The Outrage is a fun story. We alluded to that a little bit earlier too, but that was 16 pages. It was about the love of the early ’80s who went off and got rich. And then you got married to Judd, who I think is Justin.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah.

Alex Grand:

Just the name switch a little bit. And then there was this thought of Roy just kind of getting rich. And this is interesting because a lot, and this kind of goes to what Robert Crumb was saying about you, is that you don’t put yourself out as the perfect winner or the perfect victor. You put out even the things that you might have some weird feelings about, or even that a lot of people would be embarrassed about, but you put it all out there. There’s no filter.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, that’s the comic where I do talk about how I get overwhelmed with rage over… Yeah, he took my energies, a lot of stuff we worked on together. Maybe it wasn’t specifically exactly lifted from my sketchbook, but it was certainly lifted from the time where we evolved together. And it just struck me when I was at my lowest. And it seemed like, “Oh, he wins the art game and I’m the loser. And I’ve got this baby.” And I had lost my milk that week. And I had what they… You get postpartum depression, but you get postpartum psychosis. You can get that after you’ve stopped nursing. I didn’t realize that nursing can defer postpartum depression.

Alex Grand:

It kind of holds on to some of the pregnancy hormone doing that.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah. Yeah. So I crashed, I was having a crash when I saw that show. And that’s when I thought I’d stab her to death. Whole thing, it was wrong, my brain was wrong. My brain was off. I had to get help, but they didn’t know what that was back then. Now they know it. If there are women who are having this problem, they can even have a tendency of that. But there was not even a tendency. I remember going to the emergency room, they sent me to a psychologist and it was shameful and embarrassing. It’s stupid.

Alex Grand:

No, but I that’s interesting that you… And that you expressed it and published it.

Carol Tyler:

And so many women have come up to me and said, “I’m so glad you did that. I’m so glad you’ve revealed pregnancy and motherhood to be exactly what it can be for some of us.”

Jim Thompson:

It’s not just the narrative. It’s not just that you told a story. It seems to me that your storytelling really takes a leap up in this. And maybe it’s because you had enough space to do it. But those images are really, really powerful. Not to say that others weren’t, but the transformation of you, of your body, as you’re losing it and becoming demonic, is I think the most powerful work you had done up to that point. Now, of course, you get to, and we’re going to do it next, segue to You’ll Never Know, but those 12 pages just kick in terms of conveying just how desperate and how dangerous the situation was.

Carol Tyler:

Well, I’ll tell you, that was a full color everything. Everything about it. The lines, I really worked on, I’m talking about formalism now. But I really wanted every single stroke to carry and convey mood through color. And I was able to do that. So I was really happy to do that, but yeah. Hey, knowing I could do that meant that yes, I could go to the rage. I could do rage. I could use the color to enhance that. And then I was getting skilled to the point where I knew how to paste. I could pace it this way I could do this. I could show this. I could add this.

Jim Thompson:

When they told that story the same way without the color, it would have been something entirely different.

Carol Tyler:

No. So the doors were opening to color. And I did that just after that, at the same… I mean, it was like that. And then boom, got right into You’ll Never Know, which turned into Soldier’s Heart. So that was like, my kid was in college. I knocked that out. She graduated in 2003 and left home. No, she graduated high school in 2003 and left home, moved out. I got that flipped around. And it was posted in 2005, right? Late Bloomer.

Jim Thompson:

Yeah. 2005.

Carol Tyler:

And then when it came out, I went to the college up here because I had been subbing, and I threw it on the desk of the Dean of the art college. And I said, “I need to be teaching this. It doesn’t get any better than this. I can do this.” I just bullshitted my way into a job because I was sick and tired. I’d been working. I did a festival in this town. It’s like “These fuckers don’t,” I’m sitting in this meeting. They’re talking about, “Where are we going to place the trash?” Two hours on, “Where are we going to place the trash can for the festival?” Well, I can draw a trash can better than anybody here. I don’t want to do any more meetings. If I’m going to do any work, it’s going to be teaching this stuff. So I bullshitted my way into teaching a class that lasted for 16 years.

Jim Thompson:

That’s great. I know it was on comics, but what were you actually doing in it? I mean, was it-

Carol Tyler:

In class?

Jim Thompson:

Yes. Was it a how to? Was it primarily comics history? Was it a learning to do comics, hands-on kind of class?

Carol Tyler:

Actually, I did the teacher thing. I developed a mission, a rubric, standards, the whole thing. I taught them how to do it, I taught them the history of comics, and how to assess comics, how to make critical assessments based on content and form. And I never used McLeod’s book. Sometimes I had kids saying, “Are we going to have a textbook?” I said, “I’m your textbook. Listen.”

Jim Thompson:

Now, was that because you don’t agree with McLeod’s book or was it just because you didn’t think a textbook was appropriate, would get in the way of the education?

Carol Tyler:

I didn’t want it to be “Hi, I’m a consumer. I demand a textbook. Show me how we do this. And then I’ll feel like I had the outcome that I paid for.” It’s like, “No textbooks. Listen. I’m very well craft. I’m on top of my craft. You want to learn how to do comics? Listen to what I have to tell you and watch what I show you. Don’t all be going to some book that’s going to say, “Here’s how you do sequence here too. I’ll show you, we’ll read it.”

Carol Tyler:

They each had to investigate two or three arts work. So I’d say “You’re going to do Charles Barnes, and you’re going to do Debbie Drescher,” for example. And they’d have to go find the work, buy their books if they could. I had a list of people, the most repressive kid in the class, I’d give him S. Clay Wilson. “Go find some of S. Clay Wilson’s work and read it.” And then they’d have to read the work and do a report based on the assessment tool that I had drafted, which means they would have to look at the visual characteristics. They’d have to do tactical assessment and then content assessment based on things like, “How well does the character convey the mood?” Blah, blah, blah.

Jim Thompson:

So this is fascinating. And I wish we could… Because I was a teacher too for 15 years. And I would love to talk about this and get into rubrics and everything else. But we want to give You’ll Never Know a fair amount of attention. So let’s talk about that. Tell me when you realized this was going to be the big project that it was.

Carol Tyler:

I didn’t quite know. I just know that Dad had called up and said he was remembering things about the war. I remember that that was interesting to me because I didn’t have a good communication with my dad for years. And now all of a sudden, he was talking to me and I was amazed that we could talk. And so it gave us a place to connect. Like, “Chuck. Hey, Chuck.” I got to talk to him. I was no longer the pipsqueak. I could say, “Dad,” I could call him on the phone. I had a reason to talk to him in a reason to call. And so before I decided to do the thing, I thought I’d just videotape his story. And when I went over there to Indiana where they lived and sat him down and he did that thing where he was going “Turn that off, turn it off.” He didn’t want to talk about the war. I thought, “Oh boy, why not? Why not talk about it, Chuck?”

Carol Tyler:

He had this look. So I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting. I’m going to do some research.” So I got my big heavy books out and I went to the library and I did… I thought, “Holy God,” based on what he told me, his records in the photographs, I started to realize this guy was in trouble. And then it started to click and explain things. And it’s like, “I want to write about this. I want to draw this.” And the first thing I drew was the pages that talked about he was getting ready to go into chemotherapy and there was all his chemicals. I thought “This will be fun to draw.” I really didn’t know where I was going with the book. Now, I didn’t have that overview type thing. I just knew parts of it.

Carol Tyler:

He had trouble talking about it, but he was in France, and he was here, and he talked about this. My mom did this. And at the same time, this was going on so I thought “Okay, I’m going to try to pull all these elements together, give you a sense of the now, the then, and tell the story through those moments.” So the first fun thing to draw, which came right out of that story, we were just talking about The Outrage, using color to really convey was that pile of chemicals. And I used the putrid greenish yellow to show the stink marks coming off of the fumes and stuff.

Carol Tyler:

And then because that was telling about chemo. So why was I talking about chemo? Because he had resilience. So that was a quality I wanted to talk about. And how does a person who can stand down chemo, stand down cancer, the way that he did, why can’t he stand down this? I guess he has, I guess he has stood down whatever demons are bothering him. So let me explain who this guy is to the reader. So I felt like people had to know him a little bit in order to feel what he felt, feel his anguish, and to feel how I felt kind of trying to facilitate that. But I couldn’t because my life was a wreck. So you got somebody who’s interested in trying to help out as if I was capable.

Jim Thompson:

Now at this point, you had made arrangements for this. I mean, you knew this was a project. And did you have an editor that was looking at your work as you were going on?

Carol Tyler:

Nope.

Jim Thompson:

Did that happen? At some point, you made arrangements for this to be published?

Carol Tyler:

Well, I’d always published with Fantagraphics and I worked with Kim Thompson over there. And so he was just like, “Yeah, do whatever you want.” I had a handshake deal, “Hey, want to do this?” “Okay. Let’s shake hands. We’ll do this.” Did the whole thing here at this very spot where I’m at now, sent all the files by email or Dropbox, or whatever it is, over the internet.

Jim Thompson:

You sent the first volume to Kim Thompson and said, “Here it is.” What was his reaction? Because I talked about the last thing being groundbreaking, but this is beautiful in a way. I mean, this is artistic in a way that is wholly unexpected. And one of the, I think more important autobiographical things that right up there with the big ones, this is one of those. And what was the reaction by Thompson?

Carol Tyler:

I mean, he was excited. He was thrilled. He was asked me years and years ago to up my game a little bit. “Don’t do the body stuff.” He said, “You pull off the feeling stuff so much better.” It’s like, “I knew that.” I just needed that nudge, but he pretty much just let me do what I was going to do. He had faith in me and he didn’t say like, “I think on page 57, it’s not click.” He didn’t say any of that stuff. That was all my doing.

Jim Thompson:

Now. Was it your decision to do it in three volumes?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah. And I did that because my parents, at the time, well, they were getting older and older and I honestly didn’t know if they were going to make it. And so I thought, “Oh God, this is taking me.” It took me so much longer. I kept thinking of little places where I needed to add more content. And that book, as I was doing it, it was taking shape. I love that title, You’ll Never Know. But when it became, when we got all done with the three, and Kim was gone by then. Gary was like, “Nope, people don’t get it.” And I said, “What do you mean they don’t get it? It’s their theme song. It’s the things you don’t know. It’s everything. I tied the whole thing in with this title.” And he says, “Nope.”

Carol Tyler:

And so nobody ever meddled with me about anything except that Gary didn’t want the title You’ll Never Know. He said it was the publicist or somebody or I don’t know. Somebody didn’t like it up the food chain. And so it had to be changed, which I hated, but it’s fine. Soldier’s Heart is what it is. I did it in three sections because of my elderly parents. And also because it was taking me so long, I needed the buoyancy. I needed that propelling of like, “Okay, I got one. Now I’m going to go onto the second one. And then this leads to the third.” It was gaining traction.

Carol Tyler:

When that New York Times, when the first line came out, the New York Times gave it a rave view. It was like, “Oh God, now I got to live up to that. Jesus” But I kept thinking “I got to do that.” I also felt like I had done my career up until that point in fits and starts due to my parenting duties and other responsibilities. I never had the time to devote to just sitting down and doing my work. So I had this job at the college and I could do it. I could fit it in and get it done and take care of them. I take the pages up there to take care of them and it just sort of tumbled out that way. And then when I put it together as The Soldier’s Heart, I added 60 more pages. So it turned out to be a quite a big thing.

Jim Thompson:

What kind of reaction did you… I mean, could you have surviving family, your brothers, what was your family’s reaction, various people that saw it during the production of it? Or did anybody see it until it was-

Carol Tyler:

My dad loved it. He saw it and he loved it. My mom saw the first two.

Jim Thompson:

Right. I know she didn’t get to see the end.

Carol Tyler:

She loved. She didn’t get to see the end. My dad saw… He didn’t get to see The Soldier’s Heart, big thick book. But he saw the three. My sisters lived through the two. My brothers don’t like my dad. So it doesn’t matter what they think. It’s a doorstop to them.

Jim Thompson:

And your husband, because he’s a player in it too. And he’s not always a sympathetic figure in this, to say the least. Did he think it was fair?

Carol Tyler:

Yes he did. And I think I was fair to him. I think I did it pretty well. And I’ve also had to smack some people around. It’s like, “Come on, it’s a story. You know what I mean? I’m going to tell it as close as I can. But for the sake of readability, it’s not like you’re reading through like every single date has to fall.” You have to be pliable. You have to have some flexibility in things here and there. So even though it’s true and it all happened, you do have to bend it around. It has to shape into a story. It wouldn’t read right if you did it just like, “And then this happened and then this happened. And then after that, exactly this time, this happened.” That’s not the craft of the art. The art itself has to live.

Jim Thompson:

Have you talked to surviving veterans of the war?

Carol Tyler:

Yes. Yes. I have.

Jim Thompson:

Tell us about that. Because that I wish my dad had gotten to see this. He died before this came out.

Carol Tyler:

So many people have told me how much this books means to them because either a relative or like you just expressed, I’ve gone give talks at places. And people come up to me afterwards, they’re crying. I wish it had been out 20 years earlier or 10 years earlier than it did, or it had a bigger impact, reached more people. That’s okay. I don’t think my work’s on a timeline like that. But I decided to have my class, my students, have the experience of interviewing veterans and then interpreting their material. That was the lesson. To listen, interpret, and then create a story based on what you heard. So I would bring them into my classroom. I’d bring the veterans into the class. That was one of the high points of teaching, is recruiting the vets, getting them into the class, having the students do this work, and then presenting them with the original artwork afterwards.

Carol Tyler:

It was just so great. So great. And these guys appreciated me, and women. They were so appreciative of what I had done. The American Legion came and did a video of me and everything like that. And what I hate about all of this is that it’s a story about resilience, but it’s also about post-traumatic stress. And it’s about the effect of war. So it’s not glory, glory to the hero, war heroes. It’s about, again, difficult truths and what we live with when faced in certain situations, how my dad got through it and how it affected me.

Carol Tyler:

And so now that patriotism and being an American and all that stuff has been hijacked by these Patriots, they don’t like it because “You showed a soldier who was weak.” I’ve had somebody say that. “No soldiers are weak like that.” And then they’re we come to find out with the numbers being the way they are, with veterans suicides, war can… It messes with the psyche. I’m glad I wrote the book, but it just kills me the way that people have a perception of the military. A lot of people won’t read it because they think it’s about us. “It’s just a soldier book.” It’s about “Oh, I’m not interested in the military. Therefore, I’m not going to read Soldier’s Heart.”

Jim Thompson:

But you became much more in demand after this, in terms of being brought into classes. I remember, I think you came to USC when I was teaching from there. And I was super aware of your book in that context as well. It just changed who you are as an artist when you say, I mean, both in terms of perception and in terms of your ambition and what you were doing.

Carol Tyler:

Well, there was a little bit of a thing. She’s a weirdo artist, or she was in women’s, she’s a lightweight, she doesn’t finish any… Somebody said she doesn’t finish anything. In fact, there was a very cutting comment. I was at this talk in Chicago, and it was centered around some artists, some key artists of culture. Think about Gary Panter, The Crumbs, Spiegelman, Francois, Joe Sacco, Linda Berry, Charles Burns, Chris Ware. Okay. Then somebody saw me sitting there and said, “What’s she doing here?” Referring to me. And so this was 2012 and I thought, “Oh, you think I’m here because of my husband? Have you not read my latest work?” When I heard that, I was just like, “Why does this shit exist?” That bothered me. But yes-

Jim Thompson:

No one can say that after Soldier’s Heart.

Carol Tyler:

Huh?

Jim Thompson:

No one should have said that in the first place, but now they can’t say it. Right? I mean, the perception has changed.

Carol Tyler:

Thankfully, yes. It’s not said. And I think I’m not “And more” anymore. I’m “And more” on Twitter. Yeah. I mean, I told my daughter, “I would never, ever, ever sacrifice one day of being with you, that you needed me or being with you as your mom, so that I could have a bigger career as a cartoonist.” So the fact that I raised a child, she’s off and running and doing well, and she had a lot of psychological problems from OCD and stuff like that. Probably at the time when I could have hit it on a second hard, like around the time of 1997, ’98 in there, I had to back up because she needed my help. But I don’t care. What kind of timeline am I on? I just have to tell the great story. There is a creep thing going on now, it’s I’m getting old and I’ve got a big story I’m doing now. And it’s like, I must finish, but it’s so exciting for me to do this work, the one I’m working on now.

Jim Thompson:

And we’re going to get to that after we talk about the reaction to this, after the 2015 publication, what happens the following year in terms of all the recognition and things. I did want to ask about one thing. And this is because I’m a southerner, and therefore I have a great, weird love of tomatoes. I want to talk about your Cincinnati magazine. I mean, I love tomatoes. Talk to me about your one page strip that you would do for Cincinnati magazine.

Carol Tyler:

Oh yeah. This was in 2013. They called me up and said, “Hey, could you do the inside back cover?” I was like, “Yes, I’m on for that. So how about call it Tomatoes?” Because one of the things I did, there were riots in this town in 2001, racial cop killing. Terrible thing. And I should call it civil unrest because we got a lot of police reform after that incident. Well, of course what happens in situations like that often happens, is that a bunch of people packed up and moved out to the suburbs. And I thought, “Nope, I’m going to move into a neighborhood that has a variety of people because I think we need to know each other.”

Carol Tyler:

I’d gone through diversity training through the Underground Railroad Freedom Center. And I was considered to be a modern day freedom conductor. And my task, I felt, was to live in a neighborhood where I could get to know African-Americans in a way that wasn’t stupid, pressurized, or artificial. So why not just grow food? I started a community garden and that’s how I got to know people. I turned my front yard into la place where people…

Carol Tyler:

… No people. I turned my front yard into like a place where people could come, and the currency was tomatoes. That meant that I could give this guy a tomato that I grew in the garden, and then next time I’d see him, he’s in the back of a squad car, but we could talk about how delicious that was, that tomato that time. It was almost like tomatoes were the currency and they smooth things out. We got to talking and we got to know each other. The kids were calling me the plant lady.

Carol Tyler:

It brought so many adventures, and I have loved living in this neighborhood, and getting to know people just through stupid thing like tomatoes, simple thing like that. I don’t want to say stupid. So when this guy said, “Do you want to do a strip?” I said, “Yeah, I want to talk about living in my neighborhood,” so the strips every week give a little slice of life about variety of things. Generally, around growing, but generally around being, and having very casual, but… It was really… Really been a sweet look at this life in a neighborhood.

Jim Thompson:

Whether it was corn or tomatoes or whatever you had growing in your garden, you would take it, and you would just sometimes just put it on the neighbor’s front porch or… I remember when I would go back to Duke to visit, because I was teaching from LA, but for Duke. I would go back and a professor’s wife would come in with eggs and just say, “Here’s a dozen eggs,” and hand them to you, and that’s a form of communication, and goodwill, and community. A lot of people wouldn’t understand, so I just think that’s great that you conveyed that.

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, I just wanted to show normalcy, because it’s always like African-Americans are depicted in such and such a way. Well, I don’t see that here, I just see a guy walking down the street or this one’s… Sometimes, yeah, this guy over here, he’s hollering out the window, or this one over here is doing this and that. But, these are not them and that, these are people, these are my neighbors. That is Mr. Keels, that is Jack, this is Gladys, that’s Gloria, this is Iris. These are real people, and they’ve lived beautiful full lives that have had difficulty. And so, I’m just going to talk about what we all have in common.

Jim Thompson:

I just want to say that we… Because we’re trying to cover everything, but I do want to acknowledge that you had some rough years during this process of doing the, You’ll Never Know, and that you lost your mom, you lost your sister, you lost your friend Rose, was it?

Carol Tyler:

Yeah, my neighbor down the street, that’s in Tomatoes. I call her Iris in the strip, but Rose, yeah.

Jim Thompson:

… That you had to put your dog to sleep, your house was robbed twice, you got a weird disease in Europe. While you’re doing the work of your life, the best work of your life, you’re also having to persevere through all of this that could crush you, and crush somebody, and I just wanted to acknowledge that. Then you get to 2016, and everything’s being acknowledged, the success of your book. And Alex, you’re going to take us through that particular year.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, there’s quite a few celebrations that year. I think five, maybe more, but you had a gallery show at the University of Cincinnati.

Carol Tyler:

Yes.

Alex Grand:

From what they’re quoting, “This exhibition serves as the purging of the past with fragments of past projects, objects from her past and her father’s workshop. In addition, we present a collection of artifacts from her life and studio practice, which provides a look into the mind and spirit that molds her vision of the world,” and you were the cover story in the Cincinnati CityBeat there, but can you explain what that means, what they were commenting on, and what they were showing of your stuff?

Carol Tyler:

Well, first of all, I showed every single page of the book, and I had it hanging on clotheslines in the gallery. When I met with the gallery guy, I said, “I’m not going to frame this, no way. Let’s just hang it up on clothesline, I like that. I’ve done that before in a couple of little shows, previous to this, I hung my stuff with pins.” And then he said, “Okay, so what are you going to do with that second room?” I said, “Second room? I thought you just had this room,” huge, big gallery space. “No, the adjoining room, we’re giving you that room too. It was like, “Yikes!”

Carol Tyler:

Okay, so right away, I thought, “Okay”. I just thought of a giant head. I got a piece of plywood and I cut out a giant… This face I always do with the ponytail. I took a piece of a charcoal. What’s that called? Vine charcoal. I drew the big head and the ponytail, but it had to get in the doorway, so I just use two sheets of plywood and where they came together, kind of through here, this part, I’ll put this on this side of the door, this side on that side of the door.

Carol Tyler:

I cut them out, so it’s like a giant cut-out of a head. And then what I put in there, it was… The artwork I’ve been working on, is for this next project I’m working on. What I had to date, some of the art that I did, some of the single-panel things, some narratives and sculpture, because I’ve been making three-dimensional comics. I started fooling around with that, and I love that. I spent like all that time on Soldier’s Heart, scanning and correcting. You spend 30 hours on a page and then 10 hours on Photoshop for each page.

Alex Grand:

Yeah, and it’s two dimensional space, just in that for a long time.

Carol Tyler:

So yeah, I was thinking up saw blades, and drawn pictures, telling stories, and as a… Love that. I had that stuff to show, I had things like… When my sister said she had cancer, she wanted to get her hair cut, before it fell out. I said, “Fine,” and I put these things in my hair and chopped it off, the chunks of my hair… And so, I put that on the wall until… And write in pencil, write on the wall, what that was, above the drawing I did.

Carol Tyler:

I always had this thing with my students, it’s like, “Are you stuck? Do a self portrait.” So, when I was so stuck with grief, when my sister died, I did a self portrait that is so sad, so I put that above the hair. There was three dimensional things with two dimensional things, all around the space. I had a facsimile of my dad’s work bench against the wall, and a bunch of stuff, pictures, drawings, a bunch of his crap that my brothers wanted to throw away, and I kept. My drawing table was there.

Carol Tyler:

You get this immersive feel that you were in the space, and then I had it set up like, here’s all this… This is inspiration over here. This over here, are different areas, where things were going on. If you could go in there… That’s why it became the inside of my mind [crosstalk 00:07:57].

Advertisement

Alex Grand:

Yes, it was Carol World.

Carol Tyler:

It was [inaudible 02:53:00]. It was really a bear to put together, but because it was at the college, we had a lot of student helpers…

Alex Grand:

Oh, good, there you go.

Carol Tyler:

… Who made it easy.

Alex Grand:

We mentioned you were the cover story in the Cincinnati Beat. Also, you spoke at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Art Museum, on the unique challenges of autobiographical storytelling set in real time with real characters. You also spoke at the Society of Illustrators.

Carol Tyler:

It was hard.

Alex Grand:

Why was that hard?

Carol Tyler:

I was with Tom Hart, he just wrote a book about losing his child, so I called it, “The crime tour.” We were supposed to tour and I couldn’t do it. I was so stressed out by that time, by everything, that it was starting to gang up on me, and I couldn’t… I had all these symptoms, I said, “Sorry, Tom. I just… It was too much,” and exhaustion had set in. You know, you talked about being strong or [inaudible 02:54:05] to crush somebody, it started to crush me in this year.

Alex Grand:

So, even though there was all these accolades, this year is actually kind of a stressful year.

Carol Tyler:

Oh, I was a wreck, and then I was within two… You could go like this and I’d… I was always this close to falling apart.

Alex Grand:

Very fragile, okay. Then also that same year you received the Cartoonist Studio Prize, from Slate book review, with fellow recipient, Sergio Aragones. You also accepted the Master Cartoonist Award from Cartoonist.[crosstalk 02:54:37]

Carol Tyler:

No, that one I got by myself. I shared Sergio with Master Cartoonist.

Alex Grand:

Oh, okay. Oh, yes, that’s right. Yeah, with Sergio, you accepted the Master Cartoonist Award, yes, from Cartoonist Crossroads Columbus. So it’s a lot, there’s a lot of celebration, a lot of focus on you, and a lot of eyes on you. It sounds like there was a feeling of recognition, but also stress and anxiety in a way. You mentioned symptoms, what were the symptoms?

Carol Tyler:

Well, I have tinnitus real bad, so it went from having one tone, to five. I had developed [inaudible 02:55:24] stomach during the Soldier’s Heart, [inaudible 02:55:29] You’ll Never Know, because you’re hunched over the drawing table. Stomach, stress-

Alex Grand:

[crosstalk 02:55:36] like hunching over, and it’s squishing your stomach in a way?

Carol Tyler:

Just… Come on. I’m almost 70 now. [crosstalk 02:55:47]

Alex Grand:

Okay. Musculoskeletal-

Carol Tyler:

“Oh, my neck. Oh, my back hurts. All this hurts, [crosstalk 00:10:53].”

Alex Grand:

Yeah, everything just starts to hurt with repetitive motion.

Carol Tyler:

And then when you’re stressed out, “This hurts worse. Oh, no this,” and whatever. It gets worse. My friend Rose used to say, “Carol, you’re stressed, go take a bath.” “Well, I don’t have a bathtub, I don’t drink, I don’t smoke.” “So, what are you going to do, Tyler?” And I’m out… I like to… I’m not a nature, I’m not a hiker. I like to just go outside, got a dog, go outside. It’s just everything got to me, and you’re thinking too much. I was paralyzed, I’ve been paralyzed until recently. I’ve been totally unable to function. But in that, came a great joy, Fab4 Mania.

Alex Grand:

Fab4 Mania, which Jim… Go ahead.

Jim Thompson:

All right, so let’s talk about that. That seemed almost like a pallet cleanser-

Carol Tyler:

Yes, excitement, joy, life.

Jim Thompson:

Such a departure now where [inaudible 00:02:57:03], after the last work were they just… Did they say, “Oh, this is lighter,” did they take it in a critical way? Because it’s not the same markets. It’s a very… I think you had to have this book. It would seem to me you couldn’t do anything else, because you had to-

Carol Tyler:

I had to, I had to. Beatle fans love it. People who know my work for the heavy stuff are like, “Oh, well, okay, she had to do a light thing.” No, it’s really good, [inaudible 02:57:39] right?

Jim Thompson:

[crosstalk 02:57:42] I have it, and you can’t see it because my optics are weird, but it says-

Alex Grand:

There’s a shroud of mystery over it.

Jim Thompson:

“To Jim. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Carol Tyler, Comic-Con 2018,” and it’s wonderful.

Carol Tyler:

It’s supposed to be… People read it and they go like… They get the feeling, they get the, “Ooh”, the lift. It is fun, it was written in my 13 year old self, from that perspective. It is exciting, it is so different. There’s no angst, nobody dies, nobody is in mourning, nobody’s in pain. It’s just fun.

Jim Thompson:

It made me smile without any kind of conflict, just an easy smile, that’s what it is. One thing that I will… Let’s talk… Structurally, it’s okay.

Carol Tyler:

It’s my Fab lipstick. Did I kiss your book?

Jim Thompson:

Yes, you did. Oh, there’s your lipstick right there. One thing about it is, it’s structurally [inaudible 00:13:48], let’s say two-thirds of it, is building up to the concert, and then there’s the… The last part is the actual concert.

Carol Tyler:

That account is considered by Beatles’ historians to be a primary account. Therefore, it has a place in the Canon of Beatles, Beatlemania history.

Jim Thompson:

I know that you thought maybe somebody would call you. Like Ringo might call you and say, “Hey, that was-”

Carol Tyler:

Oh, I wish he would. I wish that Paul or Ringo, or somebody would call. Why don’t they call? Why doesn’t Paul or Ringo, somebody call me?

Alex Grand:

Do you have to get anything like licensing agreement to make a comic about them?

Carol Tyler:

Oh, I did ask Gary about that, and he checked. I put , “Just because I wrote, ‘I feel fine,’ as a chapter head, that doesn’t mean I’m stealing your music, is it?” No.

Jim Thompson:

No, no. I think, you’re okay.

Carol Tyler:

I’m drawing your picture based on my… All the little… Half… A lot of the illustrations, you can tell the ones I did as a mature person, but those guitars and stuff that are in there that I drew, and the little stuff on… That’s all from when I was a kid. I drew, I made their life size guitars and stuff on brown paper with pastels, when I was 13.

Jim Thompson:

One thing I experienced, I had with it, was I had just recently, last week, I think, read Dragon Hoops by Gene Luen Yang, and it’s about basketball, and his touring with his high school basketball team. They’re all that same age, they’re all young people, and they’re gearing up for the final state game, because they know they’re going to go to the state championships in Oakland. The last third of the book is the game and it’s… I was crying in excitement at that, and it was like, “I can’t believe you told a third of the book being that one thing and how it worked,” and then I thought back when I was preparing for this, and it’s the same thing. We’re waiting, and you’ve built it up, and then you so deliver in the concert. That was the trick, because if you didn’t, the whole thing was going to fall apart.

Carol Tyler:

I had to take you with me.

Jim Thompson:

Yeah, and you realize that. I wanted to say. The other thing I wanted to say is, let’s talk about lettering. I know you just were always a good… You had good penmanship and good lettering, but did you try to do this to look like when you were younger or… Because it’s such a part of the visual, as much as the art is, especially when you get toward the end. Is this part recreated, the concert in the red, in terms of-?

Carol Tyler:

Well, I wrote it in red pen, in cursive, in the original booklet, but the problem was, I wrote it on the page and then flipped the page over and wrote it on the back. For technical reasons only, I had to study and practice my 13 year old girl handwriting, and do it on separate pages so that it was print, so it was legible. But then throughout the early part of the book, where I’m just doing that, one of the things I’m learning from people is, a lot of people don’t read cursive very well, especially the young kids who are not being taught it in school, which I think is abhorrent, because how are they going to read journals and stuff, and the historical record? A lot of it is in script. Anyway, that’s my [crosstalk 03:02:52].

Jim Thompson:

In French immersion schools, they teach cursive from first grade on.

Carol Tyler:

It definitely should be in there.

Jim Thompson:

And it’s beautiful to see.

Carol Tyler:

So anyway, what I did was, I thought, “Okay, the people are going to be reading the cursive account of seeing the Beatles. I need to prepare the reader with the way I’ve laid down the text throughout the book,” so I started making the lettering. Sometimes it looks like it’s a little loopy and it leads. It’s got a little [inaudible 00:18:33]. In other words, I soften the harshness of lettering, almost like they do with the [Nillian 03:03:40] fonts, that, where you letter, but it starts to become cursive. So that by the time you get to the reading the cursive, I’ve prepared you with examples through that, the read of the early part of the book. I tried to make it easy for people.

Jim Thompson:

Oh, yeah, I know it’s great. Alex, what’s your favorite Beatles album? What’s your favorite Beatles song? Who’s your favorite Beatle?

Carol Tyler:

Here we go.

Alex Grand:

Well, that’s hard. Each one has its own story. Like the White Album is after they made their big splash, but they were kind of going to split, but I like what’s going on there, sort of more somber. Sgt. Pepper is like this big creative explosion, but-

Jim Thompson: